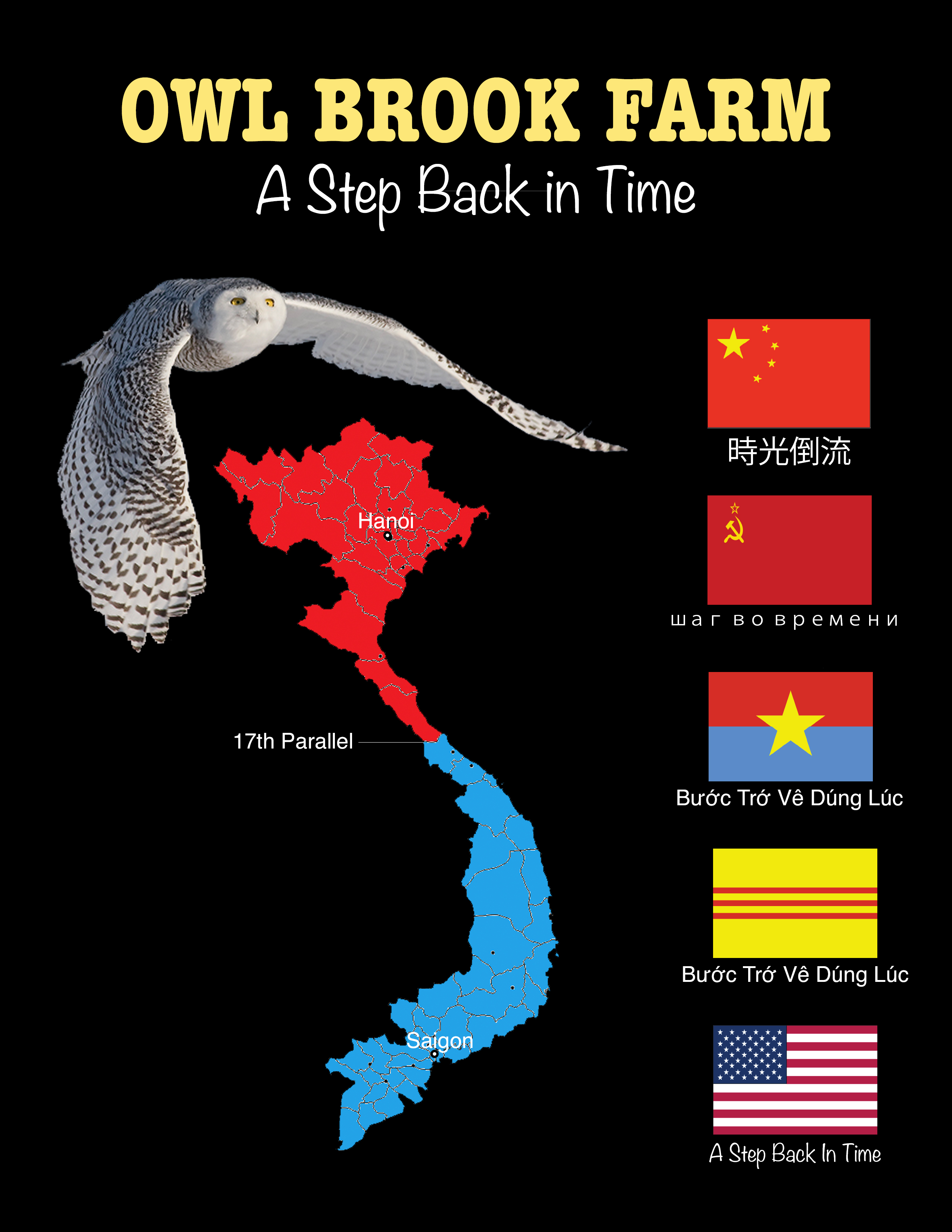

OWL BROOK FARM

A STEP BACK IN TIME

A “WALKABOUT” IN QUANG TRI, THUA THIEN PROVINCES, AND

THE HO CHI MINH TRAIL—THE TORTUOUS ROAD TO GET THERE

by Harry C. Batchelder, Jr.

“Sometimes it is necessary to go a long distance out of the way in order to come back

a short distance correctly.”

Edward Albee, “Zoo Story”

“Sometimes when you lose your way life gives you a kick in the ass that lands you

back on track . . . or in this case, back on The Trail.”

Harry C. Batchelder, Jr. • November 11, 2012 • New York City

©2016 Harry C. Batchelder, Jr.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

-

UNSOUND BEGINNINGS

Page 1 -

The Lady Shares Her Story

Page 1 -

A Visit to the Love Manor

Page 2 -

An Immodest Proposition

Page 3 -

New Year’s Eve in New York City

Page 5 -

Denouement

Page 5 -

The Fog of Love and War

Page 6 -

The Dense Fog Lifts

Page 8

-

LONG JOURNEY, LONG OVERDUE

Page 10 -

The Struggle to Find “The Correct Line”

Page 10 -

Sundays with Micheline Anne

Page 11 -

Why The Ho Chi Minh Trail? Why Not Governor’s Island?

Page 13

-

A STEP BACK IN TIME

Page 15 -

Flying the Steel Bird

Page 15 -

The Return of the Native

Page 15 -

The Airport Road to Economic Perdition

Page 17 -

Restaurant Bobby Chinn

Page 19 -

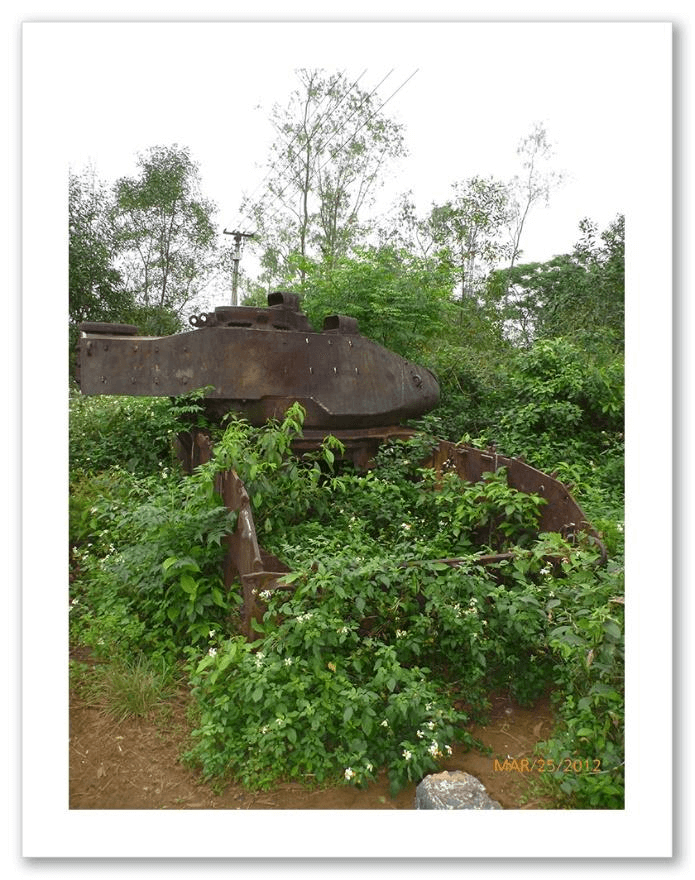

The War’s Detritus

Page 21 -

Four Pots of Tea with a Side of Versace

Page 22 -

“Has Anybody Seen General Giap?”

Page 24 -

Seeking Out the Spirit of Saigon

Page 25 -

Air Vietnam to Hue at Dawn

Page 29 -

Welcome to “Harry’s”

Page 30

– i –

-

A Long Day with Emperors Long Dead

Page 33 -

Searching for Fall’s Ghost

Page 39 -

A Walk with Comrade Chris on “The Street Without Joy”

Page 40 -

Why Routes 9, 14, and 49

Page 46 -

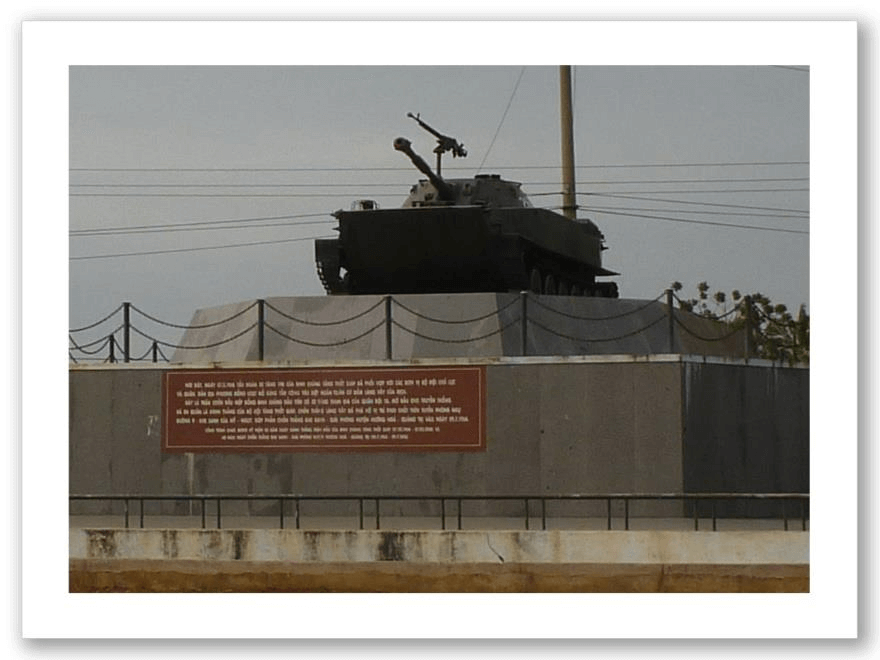

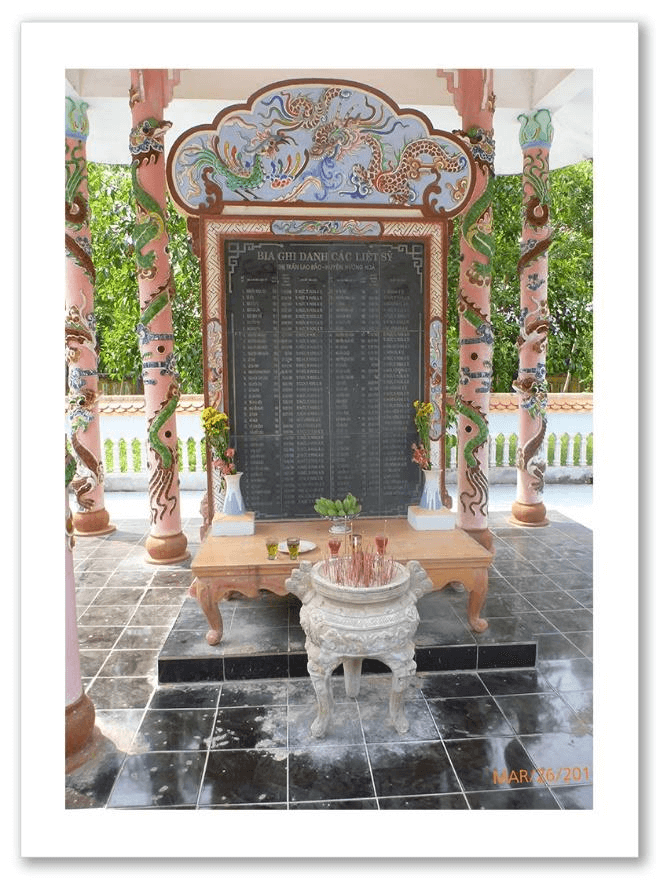

AS SEEN FROM “THE STREET WITHOUT JOY” • MARCH 2012

Page 47 -

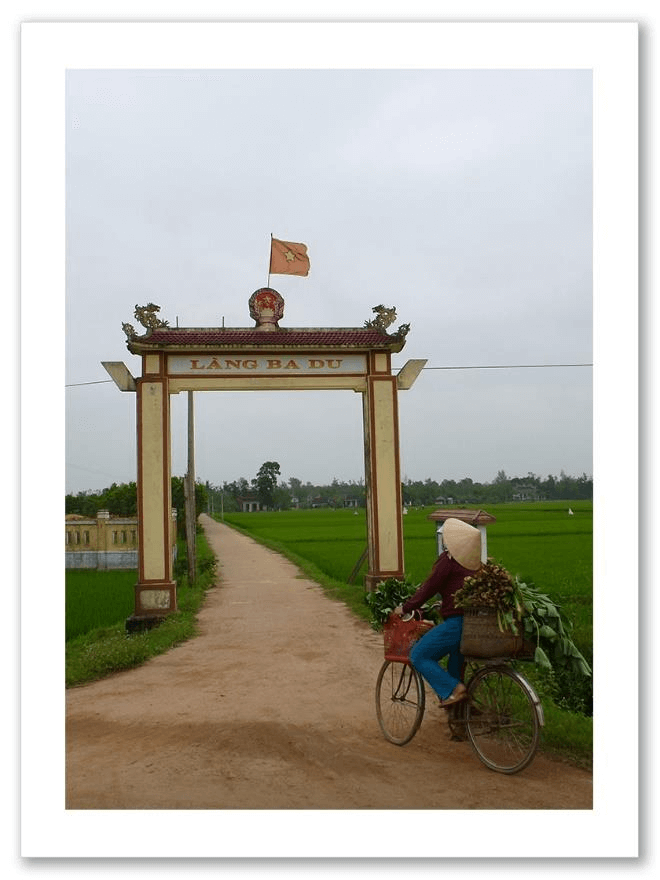

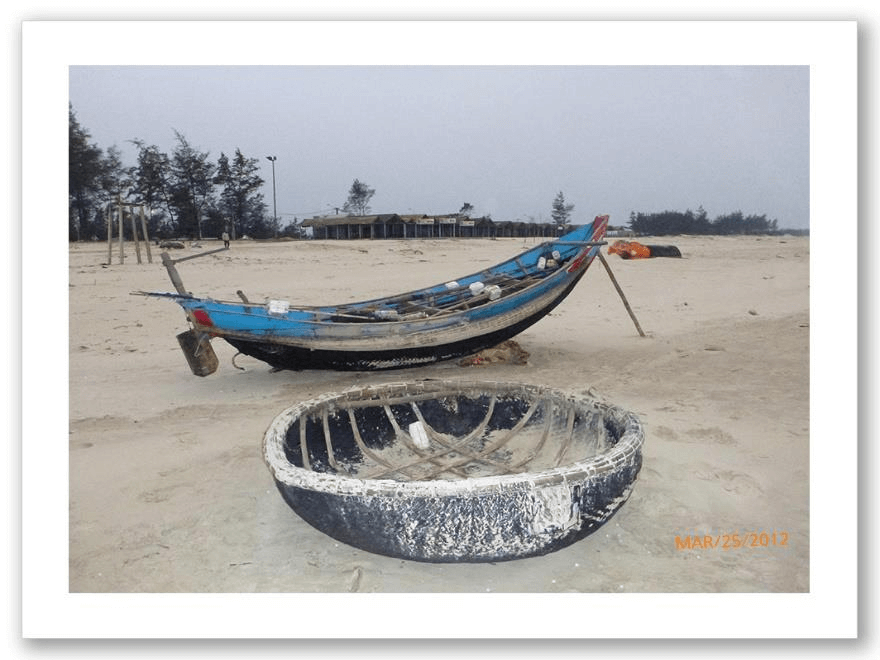

VIETNAMESE ARCHES • FORTIFIED VILLAGES • THE TREE LINES

Page 49 -

The Cam Lo Chamber of Commerce Welcomes You

Page 50 -

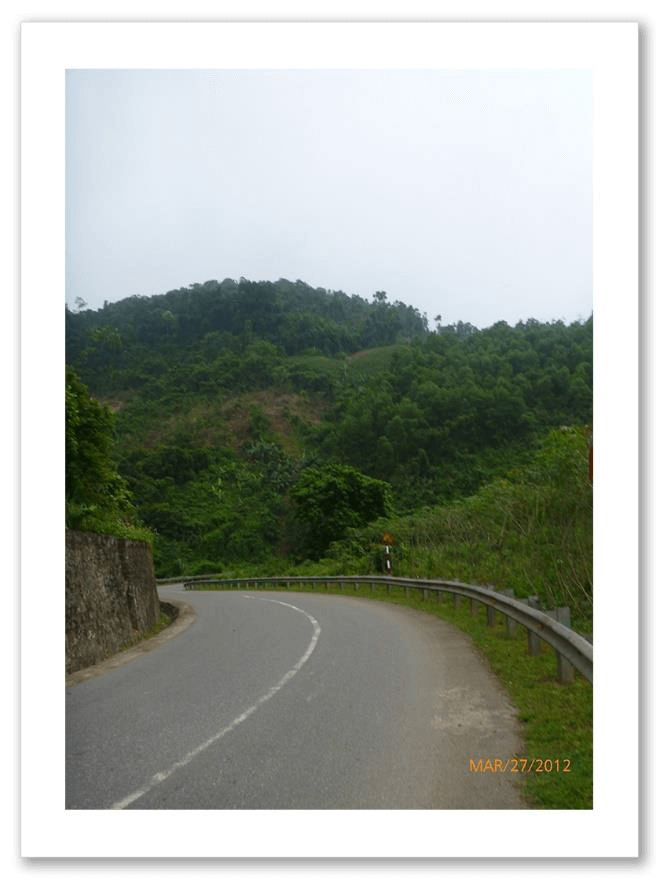

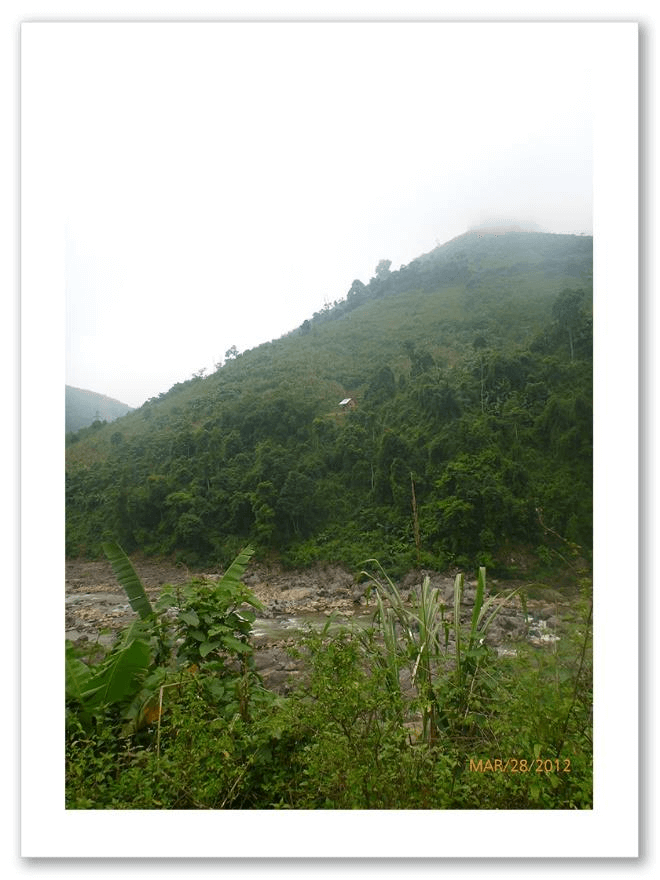

There is No Elevator to the Highlands

Page 54 -

“They Just Disappeared” “We are in the Middle of Nowhere,

Fighting for Nothing”

Page 56 -

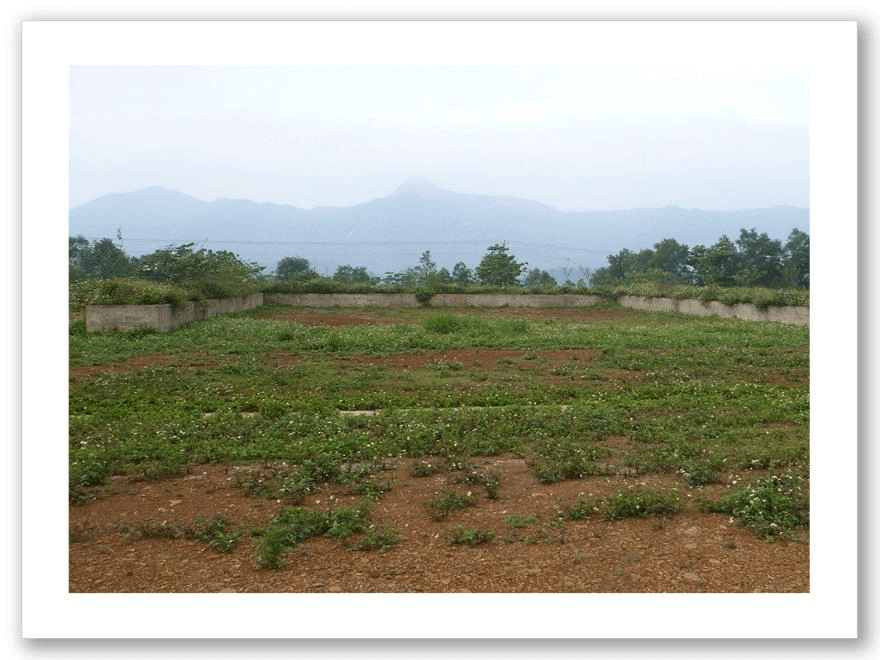

BATTLEFIELD VIEWS • KHE SANH • MARCH 2012

Page 59 -

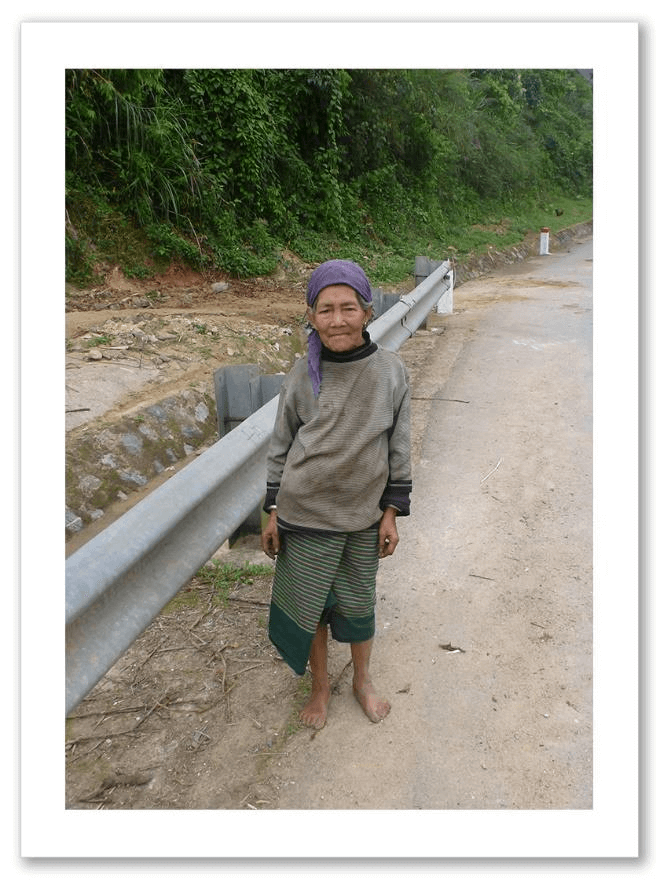

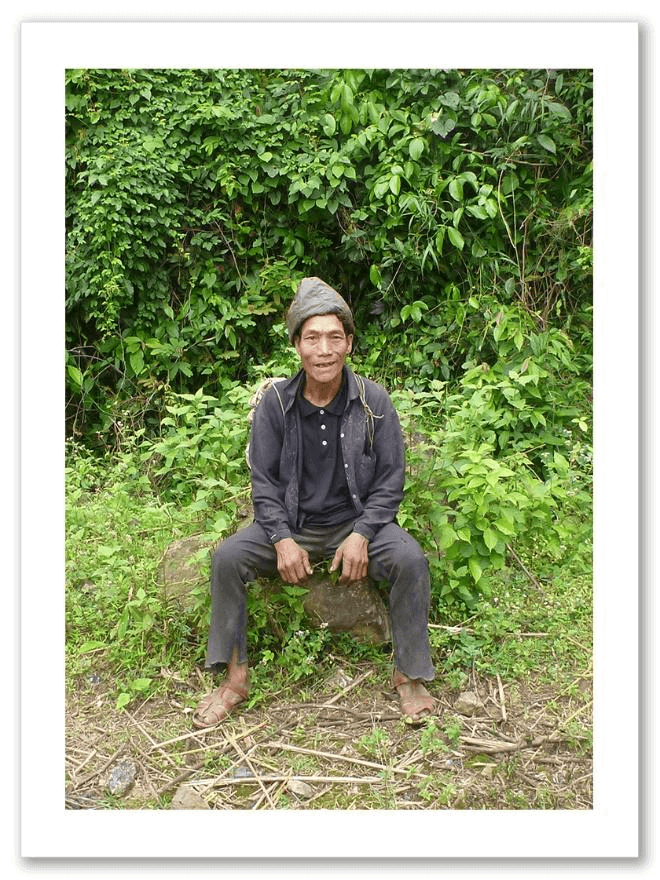

Comrade Chris: “The Bru All Became Christians,

Now They All Have Cellphones”

Page 62 -

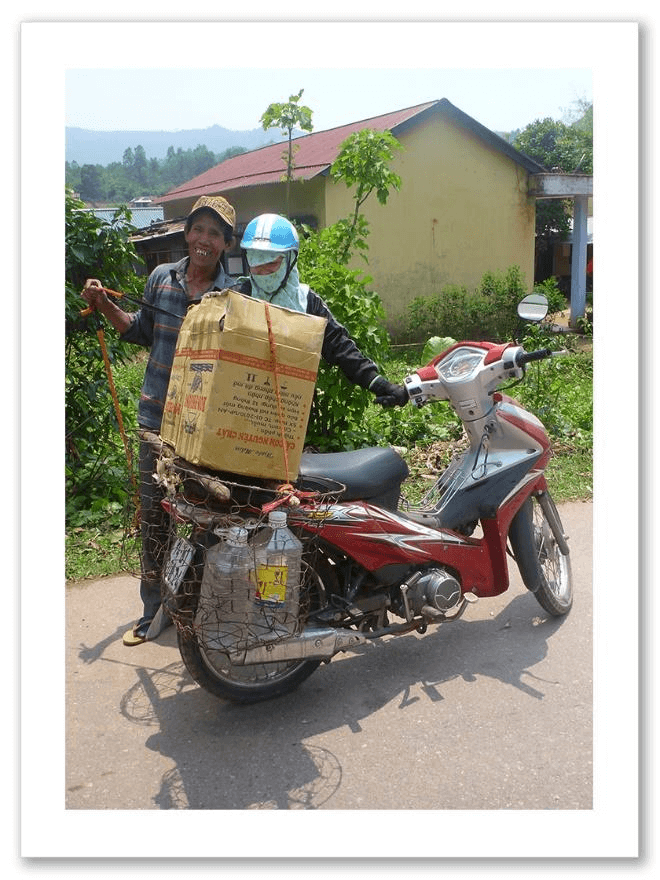

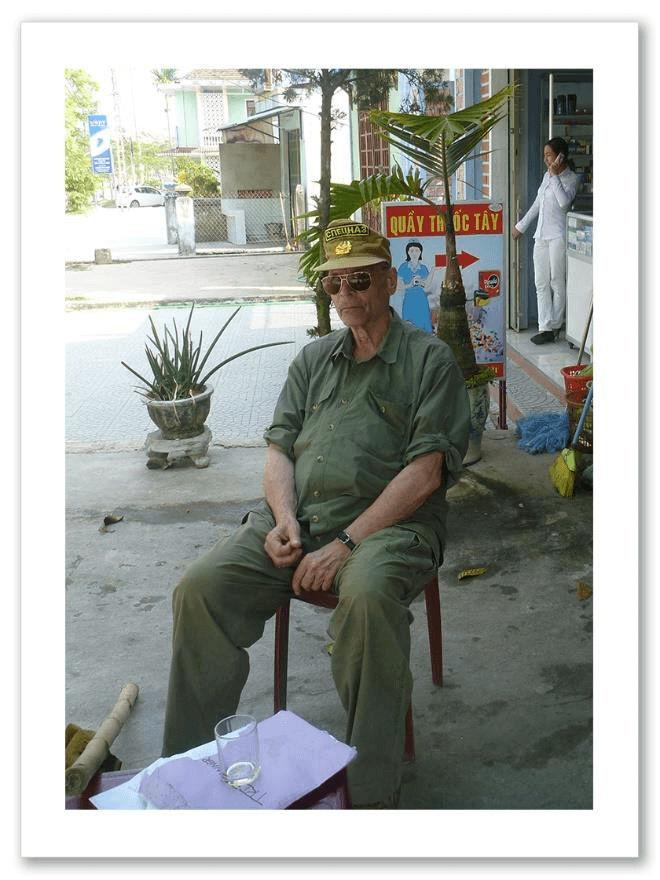

“You will be the object of attention, hospitality, offered rides

all along the way” Bamboo Boy, Lonely Planet Forum

Page 67 -

A Further Stroll Down The Trail to Meet the Wild Crowd

Page 73 -

A Night on Bald Mountain

Page 76 -

The Gay Caballeros and the Ambiance of A Loui

Page 79 -

The Way Home

Page 82 -

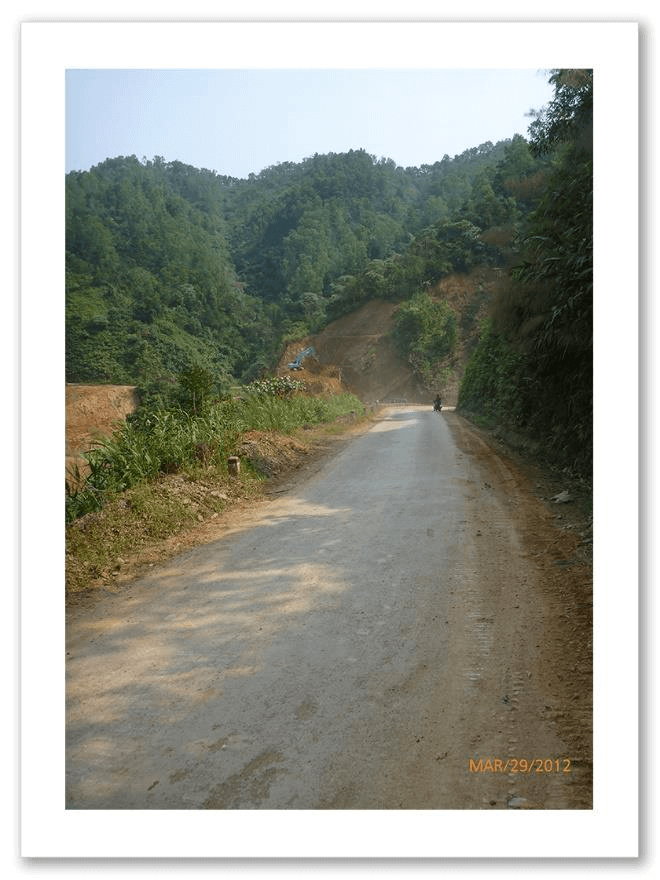

VIEWS FROM THE TRAIL • MARCH 2012

Page 85 -

Where is La Residence?

Page 86 -

HIGHLANDS GALLERY • MARCH 2012

Page 89 -

The Last Days

Page 90 -

Back into the Steel Bird

Page 91 -

Avarice and the Steel Bird

Page 91

– ii –

UNSOUND BEGINNINGS

The misadventure began innocuously enough as I found myself sharing a

ride from New Hampshire to New York City in the company of two local women,

a reasonably well-preserved sixty-something brunette, and her sister. The bru-

nette, as it turned out, was a woman on a mission; the sister was on board as her

bat woman.

The Lady Shares Her Story

From the outset I was spared the burden of making conversation. More

precisely, I was held captive to a personal narrative I found oddly fascinating.

For close to five hours, “SI” (for “Spectacularly Inappropriate”, as I came to

understand her to be) gushed obsessively about her supposedly “ex-” lover. He

was “the love of her life”, “the most charming man in the world”, possessed of

physical attributes and energies beyond those of mortal men; and (of greatest

importance, as it turned out) he was “rich as Croesus.”

As the drive continued, SI proceeded to describe a relationship constructed

on a not uncommon foundation: man and mistress shared a deep and profound

love of material wealth. Their ten years together had produced a rich public dis-

play of vulgar excess, best exemplified by construction of “the Love Manor”, an

ostentatious nineteen-room mansion the pair had built as a monument to their

love. And lest the neighbors miss the point of erecting this supersized blight on

the New Hampshire landscape, the lovers playfully conferred upon themselves

titles of “native” royalty, none too subtly proclaiming thereby their superior posi-

tion in the local social hierarchy. Even their two German Shepherds, a breed

better suited to guarding prisoners at Dachau then greeting guests at anyone’s

Love Manor, had been rechristened with royal titles of their own.

Concerning the allegedly former paramour himself, SI continued to unself-

consciously describe an individual of such inherent vulgarity that I could only

think of him as “NV” for “Naturally Vulgar.”

As SI prattled on I could hear my mother’s voice in the back of my mind

cautioning me to steer clear of people who “gave themselves airs.” But I was too

caught up in the momentum of the story to heed my mother’s words, or pay

attention to the frantically flashing yellow lights that lined the roadway. Stub-

bornly ignoring all the warning signs and signals, I pressed ahead as though the

road were clear and true.

A Step Back In Time

Page 1

A Visit to the Love Manor

As a couple, SI and NV oozed a private jet, a herd of show horses, and a

fleet of sports cars, not to mention three mansions, including the aforementioned

Love Manor. When, inevitably, I was led on a private tour of the Love Manor’s

grounds, SI proudly announced that it had taken two years to build, that it had

cost untold millions, and that she and NV had been involved in every aspect of its

design and creation.

Not versed in the finer points of architectural design and, perhaps, not

with the fairest eye, this soulless monstrosity dumped into a former cow pasture

reminded me of nothing so much as a Stalinist Georgian 1950s convalescent

home for “security types.” I espied Yagoda, Beria and Yezhov gamboling on the

lawn as they gazed longingly at a ghastly white metal Bauhaus-style storage

shed, stretching out approximately a football field in length. SI declared rap-

turously that this year-round climate-controlled paean to bad taste housed her

loved one’s collection of more than two dozen sports cars. Leaving aside the

mindless extravagance, it struck me that the sale of but one or two cars would

feed the deserving poor of New Hampshire for a year or more.

It has been my experience that these ersatz baronial visions are not quite

complete without a few life-size or larger ersatz Grecian statues punctuating the

grounds, and, once again, the designers of this particular vision did not disap-

point. SI led me to one such gigantic accent piece. She was a bit vague as to the

statue’s antecedents (Diana, perhaps?), but declared confidently that it had cost

“gobs of money.” Unfortunately, the winters had not been kind to Diana, and she

was tilting precariously. I did not have a firing table with me, but using dead

reckoning, if Diana were launched from her present position, she would clearly

impact the Bauhaus sports car shed—not such a bad thing to my way of thinking.

SI pointed out, almost lyrically, that the Love Manor was only one of the

couple’s love nests. NV had purchased two additional overstated homes, one of

them on an island much favored by local “Lake Society” (or, to my mind, “chat-

ter-box society.”) SI noted that, although a boat ride to their island property

would take at most fifteen minutes, NV had purchased a seaplane. The island

was peopled by the nouveau riche and self-styled “literati and glitterati”, and NV

wanted to arrive in style, preferably just in time for sundowners with the Happy

Valley crowd. I had visions of the Pan Am Clipper arriving in Lisboa circa 1939,

although in this case without the classy passenger list. SI stated that she and NV

were as one in believing that “a grand entrance is everything in life!”

Page 2

A Step Back In Time

During the tour, SI shared a touching tale concerning a recent addition to

her paramour’s sports car collection. NV had purchased an Aston Martin for an

obscenely staggering sum of money but in doing so failed to realize that even he

must take a six-hour lesson just to get the car off the lot. SI noted that NV had

failed to coordinate his schedule with hers, causing her to miss “a most impor-

tant” warm-up for “a most important” horse show. SI was most upset by NV’s

thoughtless inattention to her needs, and a lover’s spat ensued. I can tell you

that, by this point in the tour, issues of gross insensitivity were much on my

mind. Get real—get a life—better yet, get a Zipcar or a dozen Zipcars. They are

cheap. NV could purchase a fleet of Zipcars for what he paid for the Aston.

In hushed tones worthy of the divulging of a state secret, (but more likely

dictated by the arrival of the Love Manor’s Dominican overseer accompanied by

one of the German Shepherds—what did the man think I was going to do, nick the

olde familia plate?) SI murmured confidentially that NV possessed attributes

well beyond his prodigious “native” talents. These, coupled with SI’s declared

enthusiasm for the many Shades of Grey, kept the lovers’ pot-au-feu constantly

on the boil. The amorous pair allowed it to be widely known that they were ripe

and ready for action—so long as the action didn’t startle the dogs, they were up

for it.

Ruefully, SI acknowledged that, like all great men, NV was more than

generous in sharing his talents. Word travels fast in small communities, in this

case even faster, sped along by SI’s ringing endorsements. NV was apparently

human catnip, all that and quite a bit more, to the deserving and undeserving

alike—un homme pour tout le monde. Some of his acrobatics were reportedly

spectacular to behold—laissez les bon temps rouler!

As I exited the Love Manor’s grounds, I could swear I saw Heathcliff in

“native” garb serving those delicious little canapés to the same crowd that Tom

Wolfe so exquisitely skewered in Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers.

I violently dispatched Yagoda, Beria and Yezhov using a Makarov 9mm for good

measure. It had been a most spiritually uplifting tour. Mont Saint Michel by

seaplane—now that’s something new!

An Immodest Proposition

SI remarked that with their private jet, herds of show animals, attend-

ance at car and horse auctions for “over-the top” purchases of exotic autos and

Tennessee Walking Horses, lofty status in chatterbox society, and “native” titles

A Step Back In Time

Page 3

of empowerment, life was very good. But, as is often the case in her lover’s

world, “very good” had become “not quite good enough”; and so, despite their

numerous awards at horse shows, and their unapologetic self-indulgence in all

manner of exotic “native” delicacies, after ten years of bliss (“was it really that

long?”) SI sadly acknowledged that the couple were apart, and “very much

estranged.”

It was here that SI announced gamely that she was launching a “Golden

Age Sweepstakes” to see who would be the lucky man to succeed NV in her

affections. Although not disclosed to me at the time, one such Sweepstakes had

already taken place which, I later learned, had resulted in disastrous and some-

what scandalous consequences for the contestant. [N.B.: it is my considered

opinion that, if the collective emotional baggage of the parties involved were to

be lined up at the Equator, the results would circumnavigate the globe twelve

times.] SI’s sister thought I would make a good if not ideal candidate and, since

NV wasn’t around, what the hell, SI needed some entertainment. Looking back, I

can only conclude that this was the moment when my lifelong competitive streak

took off at full gallop, leaving my better judgment eating its dust. I looked up to

the emotional hills and mountains, and, accepting SI’s repeated assurances of

deep estrangement, I agreed to enter the Sweepstakes. I subsequently found out

that on the very day I joined up, SI contacted NV and informed him that she

would now be seeing me. I wonder, why would she do that? As they say in my

neighborhood, “calentar la plaza!”

According to SI, she had “serious issues” with NV, and they were not on

speaking terms. However, soon after I entered the Sweepstakes, and apropos of

nothing, SI told me (how exactly had she gotten this message, by semaphore?)

that NV was leaving a hopping European capital where he had a baronial flat

complete with servants to return to one of his stateside mansions (this one

located three miles from her own modest home) to enjoy the balmy New Eng-

land winter weather. Finding myself put in play as a cat’s paw did not produce

a pleasant feeling. However, given everything I had been told about the depth

and breadth of their separation, I decided to stay the course. I looked up to the

emotional hills and mountains one more time, and I still did not believe that

they could get their joint artillery up there. For a while, SI’s assurances came

like raindrops at the beginning of the monsoon. However, soon after his return

to the neighborhood, references to NV began to clutter her musings: “how

charming”, “how debonair”, and “sure there are some blemishes, but boys will

Page 4

A Step Back In Time

be boys.” I heard the words but chose to ignore the clicking sticks, and I

soldiered on.

New Year’s Eve in New York City

Under the right circumstances, New York City provides the ideal roman-

tic setting, never more so then during the holidays. SI was coming to visit her

son and I planned on spending New Year’s Eve and Day with her. On the after-

noon of New Year’s Eve, SI and I had lunch with her son and friends at Rolf’s,

which was decked out to the hilt with German holiday decorations; then off to

MOMA and the Diego Rivera murals for a bit of revolutionary top-up; and then

on to Lincoln Center to see “Blood and Gifts”, a J.T. Rogers play that chronicles

the development of a C.I.A. case officer in the First Afghan War. I attempted to

introduce SI to the role of a case officer, explaining that in the course of the play

she would undoubtedly see manipulation, lying, deceit and betrayal, all for the

“greater good” (irony unintended.) SI appeared pre-occupied; it was becoming

clear that her attention was elsewhere.

During the play SI received a cell phone call and left the theater for ten

minutes. When she returned, she was obviously not back in the theater but

somewhere very far away—life was beginning to imitate art. I admire a good

psychological operation as much as the next man, and this one was done beauti-

fully; I just didn’t care for the fact that it was being done to me. I almost, but not

quite, wanted to congratulate them on the timing—how did NV know we would

be in the theater? As Mao teaches, good intelligence is everything!

Although the rest of the evening was intended to be light fun ending up

on the Brooklyn Bridge at midnight, I might as well have been with Madame

Nhu. SI informed me that she must return immediately to her son’s apartment,

and our parting at 1:00 am was about as romantic as a beer-fueled freshman

fumble at the dormitory door.

Denouement

“Salute to Vienna” was for years a Christmas gift to me from my late

sister—the event is upbeat, romantic and a special way to start the New Year.

Le Colonial, for those who love Southeast Asia, is one of the most romantic

restaurants in New York, a step back into a 1920’s planter’s house in Cochin

China. It was my intention to ask SI during dinner at Le Colonial to travel with

A Step Back In Time

Page 5

me to Vietnam where I hoped to exorcise some demons, the Lao and Cambodian

issues having previously been laid to rest. What could go wrong? Plenty!

The concert was enjoyable. How can anyone screw up Strauss waltzes and

polkas? Nevertheless, SI appeared out of sorts, and complained that the music

was “tricycle” music. I had never heard Strauss put down quite that way, but

even I, belatedly to be sure, was beginning to recognize that a sudden slide into

ice cold emotional waters might be something other than invigorating.

The walk from Lincoln Center to Le Colonial skirts the southern extrem-

ity of Central Park, and is generally pleasant. During the walk SI said little but,

when she did, it was in keeping with the festive spirit of the day. She carelessly

announced that when “they” came to New York, “they” always came on NV’s

private jet for shopping sprees and time to recover from the plastic surgeries

that fed his vanity. Naturally, whenever they were in New York they stayed at

the Waldorf, with their personal limousine on call to take them to all the latest

“in” and “hot spots”. SI cheerfully described the splendors of The Waldorf Astoria

lobby where she and NV would relax while they waited for their limo. As we were

going to pass the hotel on our way to the restaurant, she generously offered to

give me a tour. I politely declined the invitation and looked to see if she was

wearing a sensitivity meter; she appeared to have left it at home. It would soon

become clear that this was not an oversight.

The Fog of Love and War

I recognize heavy duty incoming and this was not the 75mm and 105mm

stuff of Dien Bien Phu. This was the 130mm, 152mm, Khe Sanh stuff coming

straight in from Ca Roc in Laos, all of it expertly laid down and not fired for

effect. I got the message loud and clear, and I decided it was going to be inter-

esting to see how they pulled it off. I didn’t have long to wait!

Le Colonial is frequented by, among others, individuals who, as identified

by Jean Larteguy in his book The Centurions, have been emotionally seduced and

infected by “la fièvre jaune” of Cochin China. Put simply, Le Colonial is a most

romantic and nostalgic haven for those seeking refuge from a blustery, cold,

rainy New Year’s Day. Me—I was just frantically trying to find an emotional fox-

hole—I never had a chance! For those of an operational bent, almost all of the

seats face the door with a wall at your back. I had barely ordered drinks when

SI opined again that her ex-lover was “the most charming man in the world.”

She wondered aloud why “they”, in their Waldorf Astoria salad days, had not

Page 6

A Step Back In Time

discovered Le Colonial. Silently I gave thanks that Le Colonial is not listed

in The Big Apple Guide for the Terminally Avaricious! The conversation and

the temperature at the table felt like naked al fresco dining in Sapa in January.

I could tell that SI was not feeling la fièvre; in fact, she was somewhere between

Mars and Uranus heading out. I paid the bill and ventured out into the cold, wet

night, to walk the thirty-three blocks to her son’s apartment.

During the rainy walk, SI waxed lyrical about the ten years of bliss she

spent with her former love—selective amnesia was much in play during this

soliloquy. One wonders, just what was the attraction—or does one? For close

to a city mile I was lectured about the joys of the obscenely rich life. This was

Thorstein Veblen on acid! The emotional 130mm and 152mm fell like driving

rain, and then for good measure she added Willie Pete every third round. The

tubes were glowing and burning up!

Fiercely, a word SI adores, I was attacked for my scandalous lèse-majesté

in pointing out that if NV had, to put it charitably, “strayed”, there were better

than track odds he would “stray” again—and, by the way, nobody’s getting any

younger. Some of these “falls from grace” were widely known and quite close

to home. SI’s retort was that “bad boys are more interesting and fun.” True

enough, perhaps, but for how long until the sharing act wears thin—ten years is

a long haul. There must have been other benefits. SI “fiercely” defended NV’s

“style”, “dash”, “flair”, “savoir-faire” and another trait that decorum prevents

me from mentioning. At this point, I had a few adjectives and even some choice

nouns ready to throw into the mix, but, reminding myself I was a gentleman, I

chose to exercise restraint.

Proudly, perhaps believing she had coined the phrase, SI declared that she

and NV “were made for each other.” At that moment, in 3D no less, a vision of

Tristan and Isolde flashed before my eyes. By the time I reached Twenty-fourth

Street and Second Avenue, mahquibs, phibobs, nats in Converse Red Stars, trolls,

jinns, a veritable Murderers’ Row of evil animist spirits were furiously gnawing

at my heart and ass. All of the members of SEATO were there (except for the

Pakistani jinns who were delayed clearing customs at JFK.) I knew if the “Day

of the Dead” crowd arrived, I was going down hard.

For the next ten minutes, this gay miasmatic carnival of evil spirits was

going full bore, the spectacle orchestrated, and I date myself with this one, by the

Joshua Light Show. I spied Veblen accosting the few passersby, proclaiming that

he had joined the “Chicago Boys” and was now a “supply side” devotee. No one

A Step Back In Time

Page 7

appeared amused or interested. My last stronghold against vulgar materialism

had been overrun.

My reverie was interrupted by SI who indicated that, because of my scan-

dalous affronts to her ex-lover, she was dismissing me from the “Golden Age

Sweepstakes.” I need not escort her the one remaining block to her abode nor

accompany her to the bus station on the morrow. Although still reeling from the

emotional carpet bombing, I replied that a gentleman does not leave anyone on

a New York City street corner on a cold and rainy night. SI answered, with just

a whiff of classless arrogance, “have it your own way.” Although I admired the

pithiness of the retort, truth be told, I thought it a bit lacking in grace, and per-

haps even bordering on the inconsiderate.

During the one block walk, SI was still “fiercely” blazing as to my lèse-

majesté in pointing out certain obvious truths about her ex-lover. She then

heroically announced that her “true love”, and here she dropped all pretense as

to the real status of the parties, had, upon his return from Europe, immediately

and repeatedly pledged, garanties en béton, his “eternal love”, promising that

once they were together in one of his three baronial homes, all would be right

with the world!

I have never known “eternal love”, nor do I at this late date ever expect

to experience it. However, in SI and NV’s case, no matter how delusional the

concept, I finally grasped that it was not a belief to be trifled with. Time for me

to withdraw, and best to leave the field gracefully. Our parting that evening was

subarctic—good manners only move people with manners—il faut en finir!

The Dense Fog Lifts

At this point, friendly furies took pity upon me. Earlier in the day, before

the Waldorf Astoria fusillade, I had bought SI a piece of spray paint street art

which she left at the restaurant—this oversight was to have unimaginable con-

sequences for me. I returned to Le Colonial to retrieve the drawing, and as I

entered the restaurant, Larteguy’s “yellow infection” embraced me and the tem-

perature on all fronts rose considerably. Feeling like a damn fool and a lot worse,

I paused to take stock. Although found wanting in the “Golden Age Sweepstakes,”

emotionally battered, and facing the despair that haunts defeat, I was nonethe-

less still standing. Thus did the knocked-down-three-times-get-up-four phoenix

raise its head, as I closed out what up to that point had been a psychological

Page 8

A Step Back In Time

descent into the abyss. The true adventure was about to begin, as I prepared

to return to the land of mental and physical anguish that still haunted my soul.

Given that the recent mardi gras of manipulation and deceit had not actu-

ally killed me, it was now time to challenge myself physically and mentally to

see if having survived the ordeal had made me stronger. As I left Le Colonial

that evening, I took, as Mao would say, my first tentative step on a long journey,

long overdue.

In Kaneto Shindo’s 1960’s film “The Naked Island”, a hauntingly tragic

exploration of the savagery and despair of Japanese peasant life, there is no

spoken dialogue. Allow me to assure everyone that the cab ride to the bus ter-

minal—sorry baby, no private jet—made “The Naked Island” look like a simultan-

eous three-ring spelling bee. To enable SI to return as expeditiously as possible

to the land of “native” royalty and “eternal love”, I arranged for her to take an

earlier bus. Speaking as a gentleman, I wished SI and her lover every happiness

and I meant it. Who knows, perhaps SI’s “fierce” defense of the spiritual as well

as material benefits of vulgar wealth had made a true believer out of me!

I wait in vain for a thank you for the weekend which I still thought was

a triumph of planning, even though it lacked a certain something in execution.

A Step Back In Time

Page 9

LONG JOURNEY, LONG OVERDUE

The Struggle to Find “The Correct Line”

Over the next several weeks I renewed my intellectual friendship with

Mao, On Guerilla Warfare; Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom; Fall, Street

Without Joy; and Larteguy, The Centurions. Locating up-to-date maps of Viet-

nam’s Central Highlands was a problem, and the New York Public Library Map

Room had nothing on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Google Earth came much into play.

The game was beginning to shape up.

Mao believes that in order to have a sharp mind you must “savage” (his

word) the body, and so I set about to do just that, or at least build up enough

endurance to walk twenty-five miles a day. I joined the Harlem YMCA as one of

the few, if not the only, geriatric white males looking to become part of the gym’s

“animal kingdom.” No free weights, thank you. A good friend had laminated an

image of the grotesque Stalinist arch at Lao Bao as a reminder to me to press on

when I faltered on the treadmill.

Once the regulars determined I was not a geriatric undercover cop, I was

treated with the utmost courtesy and respect; once they saw the picture of Lao

Bao and understood what I was planning, several of the older guys urged me

to extend the workout to include a series they called “funning.” The routine in-

volved crunches, low rowing, and lats, and utilized every machine for developing

the upper body. They suggested this program might come in handy should any

trouble arise during the “walkabout”.

I continued my workouts, the pounds started to come off, and eventually

I could hold my own—the “savaging” was working. As I approached peak fitness

for a man in the prime of his seventy-sixth year, I thought of Mao’s highly touted

propaganda plunge into the Yangtze River. The seventy-two-year-old Chairman

paddled in circles and floated on his back for a little more than an hour among

the bobbing heads of countless cheering comrades. I would be hiking solo on the

Ho Chi Minh Trail, eight to ten hours a day, without so much as an “attaboy” from

the sidelines.

In another development for life-long use, I learned that if one plays the

“Internationale” five times back-to-back, you can handle anything the bastards

throw at you. As my endurance increased I could feel myself getting pumped up

mentally as well. I grew impatient to go—the sooner the better. Brushing off the

Page 10

A Step Back In Time

last remaining crumbs of emotional stupidity, I bid farewell to the sorry smell

of second-hand curry, and reset my sights on Saigon.

Sundays with Micheline Anne

For the very early advisors to Southeast Asia the conflict was intense,

personal and, on occasion, rewarding: Never to be forgotten, you were there

“doing good!” In his personal narrative, The Village, Francis J. (“Bing”) West

exquisitely details the wrenching panoply of emotions experienced by young U.S.

servicemen in the carnival of death atmosphere of Vietnam. Inevitably, despite

the environment and circumstances, friendships developed, and relationships,

intimate and unexpected, took root.

As a disciple of Lawrence, you never slept with the women in the country

to which you were assigned—never, ever. This prohibition constitutes madness

for many, but was not an issue for me; besides, my heart was elsewhere.

By chance, I met the mother of a thirteen-year-old young lady of mixed

French and Vietnamese parentage. Micheline Anne was not terribly attractive

physically but possessed of a universe of innocence and class; I saw in her a light

that would one day travel round the world. Because the air was still French, she

had not yet been ostracized, which, as the war dragged into decades, would be-

come the fate of thousands of mixed children. Her father, a French legionnaire,

had abandoned the family; her mother, occupied with “other things” (charitable

words) had little or nothing to do with her. Micheline Anne spoke broken Eng-

lish, was hard pressed to find the money for school, and was condemned to a life

of indifference or worse with no hope of escape. Enter the big blue-eyed men

from the East. Back to school, (Catholic—what else) and a friendship was born

that burns as brightly today as it did fifty-three years ago.

Each time the men from the East returned to Saigon we sojourned to the

sidewalk café on the terrace of the Continental Hotel. Three strapping Americans

and this teenager in her Catholic schoolgirl’s uniform—not your everyday assem-

bly. The ritual was fixed: Cokes all around—no Perrier for this crowd. Micheline

Anne, very much the lady, held court—an island of innocence surrounded by a

sea of violence, chaos, and deceit. The relationship and emotions that resulted

were intense. I can only compare them to those portrayed in the 1962 Serge

Bourguignon film “Sundays and Cybele”, which, when I first saw it, wounded me

beyond despair for months if not years.

A Step Back In Time

Page 11

Micheline Anne’s English improved, her grades soared. I told her if she

did well I would send her to the Sorbonne where she could learn to be a revolu-

tionary and return to become the power behind the throne. I would have found

the money somehow. The revolutionary part I would have soft-peddled, but then

again, maybe not. Although the rendez-vous were not all that many, people were

watching, and the “struggle” soon got very personal.

Our team returned late one evening and, as she adored ice cream, I gave

Micheline Anne some piastres for the next day. She and I said our goodnights,

and went our separate ways. Back at the Continental as I got ready for bed I re-

membered a note I had received several months earlier. It had been cut out from

a newspaper and read “You shall know pain.” I was soon to learn the extent of

the pain.

Early the next morning I heard an explosion outside in the block just

down from the Continental, and I knew to a certainty what had happened. The

ice cream and candy store opened early and when I hit the pavement I saw

Micheline Anne, her body half in the street and half on the sidewalk. What was

left of her head rested in a pool of dirty water that remained where the street

cleaners had passed by her lifeless form. The Vietnamese were stepping over

her. I saw the bloody piastres in her hand, and the light went out in a great

portion of my heart, never to be lit again.

Her mother, quite properly and I did not fault her, said this would not have

happened if Micheline Anne had not associated with us. She wanted nothing to

do with the cremation, and when I returned the ashes to her she placed them in

a closet, not on an altar. She summarily dismissed me. I had it coming, but there

was nothing she could do to punish me that remotely approached what I would do

to myself in the coming years. I never heard from her again and I completely

understand why.

I have been told, professionally, that Micheline Anne’s murder has more

than colored my views on many things; a Russian doctor, no less, recommended

that I return to Vietnam to “bring closure.” I don’t understand words like

“closure”. Why would I want to “move on” from someone beyond special, whose

memory endures unchallenged in my heart’s embrace. In my mind, so long as

I am alive to remember her, Micheline Anne is immortal; when I die, she dies. I

would gladly give up a thousand lesser memories to sit with her again, sipping

Coca Colas on the terrace of the Continental Hotel, and savor those halcyon days,

Page 12

A Step Back In Time

all too few, when a big blue-eyed man from the East and a French-Vietnamese

young lady, discarded by her mother, fused an emotional bond beyond steel.

Get over it—no—I wanted to meet up with Micheline Anne and start all

over—closure be damned! What do those Russians know anyway! Emotionally

dead, thanks to the Five Year Plans. Still, the doctor was one of the very few who

wholeheartedly supported, no, encouraged the “walkabout”; where others were

horrified by the idea she was gung ho. I must learn to cut her a little slack.

Why The Ho Chi Minh Trail? Why Not Governor’s Island?

By way of background, military intelligence schools in the 1950s and

even to this day tend to turn out “bean counters”, which totally ignores the

political aspects of revolutionary war. This is not meant to fault them, as they

see their mission as one of “pure intelligence”, and to slip into that “other world”

is to risk corrupting their mission. The Pathet Lao/Viet Cong crowds (not to

mention whatever Khmer mass murderers were around at the time) were not

burdened with any such constraints. As noted by Larteguy, and also by Fall in

Street Without Joy, our adversaries early on embraced the concept that military

tactics are of secondary importance—politics will always take precedence. We

have yet to master an effective response to this critical hierarchy.

Additionally, the boys in black had a broadly based intelligence net spread

throughout “the masses” which provided their operations with up-to-the-minute

intelligence of such a kind and volume as to severely cripple counter-operations.

Mao preached, and these were not abstract concepts, that theirs was a war of

“movement, alertness, mobility and attack.” Lest there be any doubt about the

wisdom of this approach, consider that the nightmare effect of Tet has never

been completely exorcised from the psyche of the United States military. Fall’s

later chapters vividly illustrate how we were caught in the same trap as were the

French, indeed even on the same roads!

In his brilliant introduction to Mao Tse Tung’s On Guerilla Warfare, Briga-

dier General Samuel B. Griffith sets out in two succinct paragraphs America’s

reliance on a worship of technology in missiles, bombs, and the big bang for the

buck. The crowd in black relied on rigorous discipline, up-to-the-minute intelli-

gence, and a clear picture of what they were fighting for. This is, admittedly, a

gross oversimplification of the rights and wrongs in the conduct of the war, but

as Fall’s early insights teach, America ignored certain precepts of “revolutionary

warfare” that ultimately led us to the embassy roof.

A Step Back In Time

Page 13

In the 1950s, a miniscule minority of intelligence officers began to grasp

the impact that the tactics of revolutionary war might have on the Army, the

Navy and, to a much lesser extent, the Air Force. The minority voices were

muted and their opinions were never sought. Although they took a pounding in

Graham Greene’s The Quiet American, these officers found intellectual comfort in

the actions and teachings of Major General Edward G. Lansdale, USAF. The boys

in no-rank khaki slowly emerged from these humble beginnings. Militarily, des-

pite fierce resistance, USAF special operations squadrons were getting ready to

be birthed in the not-too-distant future.

These special ops officers slowly trickled into Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam,

and I was invited to join. I have never been invited to Governor’s Island, nor do I

expect to be—a small price to pay for social integrity. Show me your friends and I

will tell you who you are!

The Ho Chi Minh Trail was General Giap’s logistical lifeline. We bombed

it, sprayed it, mined it, sensored it, tried to build a fence, tried everything but

boiling and fricasseeing it, and we failed dismally to stop the flow of supplies. An

estimated 600,000 went down the trail and 200,000 came back. As terrain goes,

it is not much of a challenge, but if you do it solo with a rucksack and a jackknife

it can get interesting. According to the boys at the Lonely Planet nobody had

ever walked or tried to walk the trail, because for long stretches “there is nothing

down there” and no place to stop. A perfect SAS problem course. Time to “ride

the tiger” on The Trail.

Page 14

A Step Back In Time

A STEP BACK IN TIME

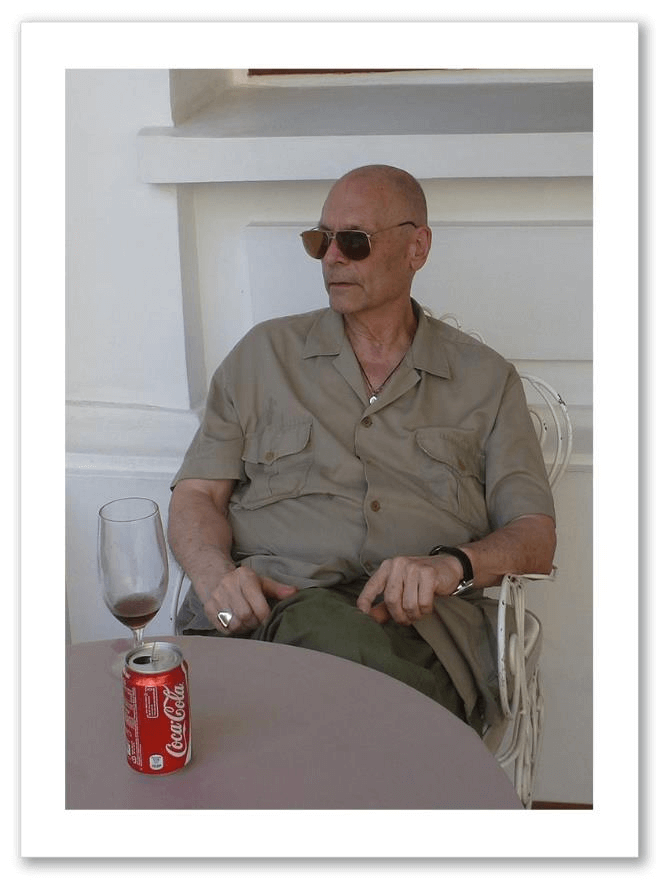

Flying the Steel Bird

Given the nature and length of the trip it was not too difficult to pack; the

weight of the historical emotional baggage was far more troubling. Haunted by

having to deal with fifty-two years of neglect, I cannot sleep the night before my

flight. Sunday morning to the gym, and I break four miles an hour on a 5% in-

cline. Cold showers galore, then into the steel bird for a thirty-three hour joy ride

to Saigon. A close friend gave me Nelson DeMille’s novel Upcountry and as I read

it I realized just how thoughtful a gift it was. I would be walking in many of the

same areas, such as A Loui and its environs.

I had a window seat and as we descended into Saigon, I immediately no-

ticed that the city’s urban sprawl had passed Tan Son Nhut. A huge golf driving

range—golf driving range?—loomed into view. We greased runway 25R and, as

we turned on the taxi way, eighteen black lichen colored helicopter revetments

loomed with landing circles still clearly visible. As we passed in review, they

were at attention like a Praetorian guard for a vanished “Contain Communism”

empire. In the old days Tan Son Nhut was “spooky” with frenetic activity; four of

the hangers remained, but not the craziness. As we turned to the docking ramp I

saw, just outside the airport, a monstrous Corona Lite advertising banner draped

on a new apartment building—it had to be one hundred feet of flag—welcome to

globalization.

The Return of the Native

Major Reginald Hathorn was, in 1968, an O-2 driver in Vietnam. In his

2008 book Here There are Tigers, he mentions his early upbringing in Louisiana,

and writes that when he first arrived at Tan Son Nhut, Vietnam smelled, to him,

“like a rattlesnake.” One of Hathorn’s first missions was to bring in “fast movers”

to bomb the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a portion of which I was to walk on the first day of

my “walkabout.”

My initial arrival experience differed from Hathorn’s because as a teen-

ager I helped my father work Owl Brook Farm, the most spectacularly unsuccess-

ful dairy farm in the history of the world. There is no greater joy imaginable for a

teenage boy than getting up at 4:30 in the morning at ten below zero in four feet

of snow, opening the door to a tie-up where thirty-two head of cattle have been

A Step Back In Time

Page 15

doing their business for the last twelve hours, and cleaning up the mess with no

mechanical scuppers!

Do this for a while and you will understand why Mao, in the previously

referenced essay, observed that “only the men of the North are able to lie under

arms and meet death without regret.” And he never experienced my father’s tie-

up! Compared to the tie-up, Saigon in the late ’50s smelled to me like a Givenchy

perfume factory.

Based on my initial observations from the air that Levittown had snuggled

up to Tan Son Nhut, I figured that if I got bored, I could hit a few golf balls and

down some Corona Lites. Then the plane door opened and it was air conditioning

all the way. I thought I might be in for some fun at Immigration, and I was not

disappointed.

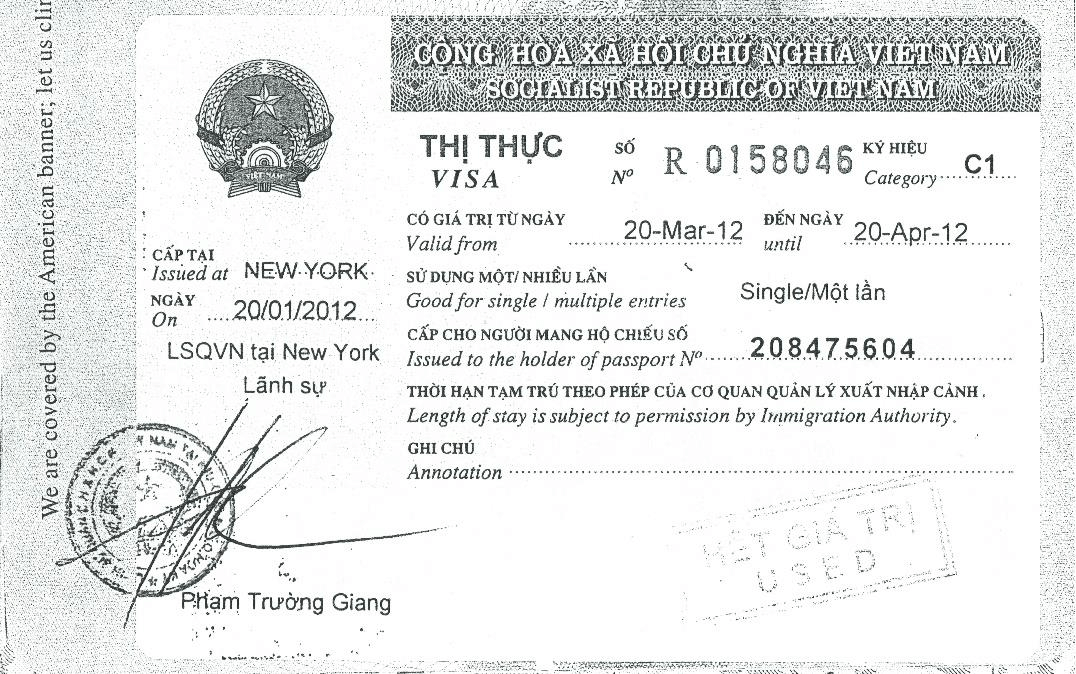

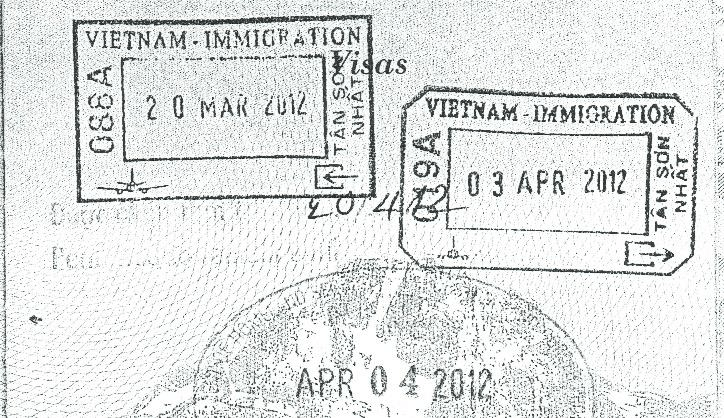

My immigration officer was, I guessed, in his late thirties, and a sharp

dresser with well-shined shoes. Reviewing my travel history he asked, in per-

fectly unaccented English, what I was doing in Burma (not, I noted, Myanmar)

before it got trendy, and why I had visited Laos twice, coming in from Chiang Rai.

I told him I was interested in “native textiles.” By this time he was joined by his

supervisor, a bit older, again speaking perfect English, and sporting an equally

sharp uniform and shoes. It was the two fairly recent Cambodian visas that

caught their attention—I decided to get in the game.

I told them that, to my mind, 2,000 Chinese visitors a day to Siem Reap

“lowered the tone of the neighborhood.” On a roll, I opined that it was a good

thing the Vietnamese had invaded Cambodia to teach the murderous Khmers a

lesson, but the Khmer Rouge were still running the country—they had just put on

suits. During this latter paean I detected a slight twitch around the supervisor’s

mouth but I was mostly locked on his eyes. He then handed me back my passport

with a “welcome back to Vietnam.” I had no prior Vietnamese visas in my pass-

port—touché! With this for starters I knew my stay was going to be interesting.

Page 16

A Step Back In Time

The Airport Road to Economic Perdition

I climbed into a cab and, within one hundred yards of the entrance to the

airport, I was floored. On both sides of the road, small entrepreneurial shops—

machine shops, motorcycle repair shops, small offices, and clothing stores—were

humming. Their density quickly increased, and by the time we had gone two

kilometers it was wall-to-wall small enterprise. To my mind, there was no way

this fit into any Five-Year Plan. As we drove further towards downtown, small,

then larger tasteful office buildings began to appear and, although it was late

morning on a business day, swarms of light-cc motorcycles operated by neatly

dressed men and women began to clog the roads. Further on, more steel and

glass appeared, as did more motorcycles. The road was a central economic

planner’s worst nightmare. As we hit downtown Saigon, the French ambiance

was almost obliterated by new development.

Arriving at the Continental, I looked over to the block where Micheline

Anne’s murder had taken place. The block, everything, and I mean everything,

including the sidewalks, had disappeared. A sign proudly announced construc-

tion of a luxury hotel, magnificent luxury condominiums, a spa, and an under-

ground parking garage. I found myself thinking about the water table in Saigon

and the money it will take just to build the garage in a city that hardly needs

more cars.

The Continental, the grand dame

of traditional Saigon hotels, subjected as

she was to the construction symphony

next door, must always be aware just how

precarious life is under Red capitalism.

As I entered the hotel I glanced over at

the construction site and vowed I would

somehow get inside. I had been back for

more than an hour and everywhere I

looked I saw clothing that could have been

bought at a southern California strip mall;

not an ao dai in sight, not even at the re-

ception desk. The physical reminder of

my despair had been vaporized, and the

soft edges of Saigon replaced by hard steel

and concrete. The economic aspirations

A Step Back In Time

Page 17

of Deng Xiaoping had found fertile soil in Saigon, and they were flourishing. I

checked in, immediately went to the front veranda, ordered a Coke, and, looking

every bit the “ugly American”, tried to get a handle on the changes all around me.

It is generally my practice, if at all possible, to walk a city, and I immedi-

ately headed for the War Remnants Museum. I took my time and I was more

than impressed. The parks were clean, no litter on the streets, no beggars, every-

one neatly dressed. The palace and every other public building were in tip-top

shape. The traffic was chaotic, but with none of the vicious New York City top-

dog aggression. To my mind, whatever they were doing had made the city livable

and aesthetically pleasing. Even the swarms of motorcyclists appeared to get

along reasonably well with each other.

The War Remnants Museum is by far the most popular museum in Saigon.

The U.S. takes some body blows here, with static displays of our various aircraft

and helicopters, and a “daisy cutter” thrown in for good measure.

As I entered the museum’s grounds I was pleased to see the iconic O-1 Bird

Dog front and center, and the sight made me proud to be a Bluesuiter. Ravens,

perhaps the greatest group of

aviators ever assembled, (and

who, as befits those who fly by

ailerons and are required to

jink every thirty seconds just

to stay alive, possess an elan

the uninitiated cannot even

imagine) had christened the

O-1 “the mightiest fighting air-

ship in the world.”

As I toured the galleries,

I noticed the conspicuous ab-

sence any exhibits referencing

the 6,000 Vietnamese who were methodically listed, hunted down and murdered

by the Viet Cong during their occupation of Hue. Despite some subsequent polit-

ical differences, the Vietnamese were, on that occasion, aping their murderous

Khmer neighbors.

On the far left as one enters the museum are a series of shops offering fake

Zippo lighters from many of the war years. The lighters display the unit desig-

nator on the front, and on the back pithy G.I. philosophies which offer a glimpse

Page 18

A Step Back In Time

into the mind of the owner and the demons of the times. They illustrate despair:

“You can fuck with the troops, but you cannot fuck with time”; humor: “If I had

a home in Hell and a farm in Vietnam, I would sell both”; defiance: “Kill them

all; let God sort out the innocents”; and profound insight: “Life is sweet for those

who have fought for it, for life has a flavor the protected will never know.” I pur-

chased the last of these and carried it with me everywhere.

Back to the hotel. My first impressions of Saigon were confirmed: a spank-

ing clean city, little poverty, and a well-fed, well-dressed populace. Clearly this

was more than trickle down Red capitalism at work. I was impressed, but I had

not yet seen the countryside.

By chance, an acquaintance of mine had met a couple from Vietnam while

they were in New York. They graciously agreed to meet me for dinner to discuss

the projected trip and introduce me to the “new” Vietnam. They chose the res-

taurant and it was my lucky day on all fronts. She was your basic ten-star Viet-

namese Cambodian knockout—charming, smart, worldly, in short, a treasure.

He was a photographer lately returned from Burma, handsome, charming and

worldly—in short, an incandescent couple. Any reticence between us dissolved

instantly when the menu was opened. To share the unique hospitality of Res-

taurant Bobby Chinn, the proprietor’s rules follow in their entirety:

Restaurant Bobby Chinn

“In the unlikely event of a terrorist hostage-taking

situation in this restaurant, please DO NOT call the Russian

Special Forces. I would rather be pecked to death by a duck.”

Restaurant Bobby Chinn Rules:

Introduction to Menu

“This restaurant is an Abba, Kenny G., and Gypsy King

Free Zone. We also refuse to play any bands with more than

one lead singer or matching sweaters. Female Teenyboppers

dressed like whores with synchronized dancing are also

banned! To preserve the dining experience, we request that

you are well versed in mobile phone etiquette (SILENCE). All

our Poultry & Meats are Halal or as close as it gets to Kosher

. . . Except the pork, of course! None of the staff were harmed

(physically) to bring you quality food and service tonight, or

A Step Back In Time

Page 19

ever. Children’s menu available upon request and duct tape

is available for hyperactive children. Please do not ask us to

split the bill other than by a number. We do not do ‘she had

this, and I had 1/2 of that’ very well. Please note that we

have smaller portions at the same prices for Anorexics and

those aspiring. Also this restaurant is non-smoking, please

smoke at outside, feel free to fart there also. Thank you.”

S E A

Cold-blooded seawater creatures that didn’t have a chance or even a clue!

Crispy Skinned New Zealand Salmon on Wasabi Mashed Potatoes,

Vegetables, Ginger Demi Glace 456

A I R

But they spent a little too much time on land, and not enough in the air.

Then there is Bird Flu . . .

And you want to know why it’s called foul?

Apple Smoked Duck Breast with Black Sticky Rice,

Baby Bok Choy & Pomegranate Duck Jus 600

Half a Rotisserie Chicken served with Root Vegetables & Mixed Green Salad 378

L A N D

Dumb cows that thought they were living in India or something.

Lambs that had no idea about Islam

The Wagyu Burger, Mixed Greens & Truffle French Fries 550

Red Wine Braised Lamb Shank with Cous Cous 640

Filet Mignon 696

S I D E D I S H E S

We tell you “You are beautiful” all night long (includes a signed copy of the menu.) 126

Grapes Wrapped in Goat Cheese with a Pistachio Crust 264

Wasabi Mashed Potatoes 130 Truffle Mashed Potatoes 306

Mac & Cheese, BBQ Pork Ribs with Asian Slaw 252

Mashed Potatoes, French Fries, Edamame 180

Nachos 276

Page 20

A Step Back In Time

For the next four hours they jenned me up as to the new Vietnam—both

were supporters of the trip and the conversation was stimulating and beyond.

They illustrated the economic development of the country with the touching

story of a young Vietnamese entrepreneur who purchased a Lamborghini.

Because of his slight stature, the driver’s side had to be modified and a special

team was flown from Italy to Vietnam to customize the seat. This was accom-

plished and he set off for Hanoi on Route 1. However, due to the poor condition

of the road (torn up from overloaded trucks) and the car’s low clearance, it was

necessary to have a tow truck accompany the car all the way to Hanoi and back.

It took the young man three days to get to Hanoi, two days longer than the train,

and four days to get back. Nevertheless, he considered the trip a success—quality

vulgarity, expressed with cachet, trumps wholesale vulgarity hands down.

As I walked back to the Continental along Dong Hoi Street I was assaulted

by Tiffany, Versace, Chanel, Cardin—every shop an icon of Western materialism

and greed. I thought I was on Calle Florida in Buenos Aires or Fifth Avenue in

New York, but Dong Hoi is a lot more intimate. I returned to the Continental, sat

on the patio, sipped a Coke, looked over at the silent construction site, tried to get

some answers and got none. I knew where I was going the next morning.

The War’s Detritus

I was taught that whenever I come to a new city, if I don’t speak the

language, I must search out the English language newspaper and read every

page. Everything—even the want ads—the lot! I arose early and got only as far

as the first page of the Saigon Post and, I believe, page seven, before I was floored

once more.

It appears that there are three mobile phone companies in Vietnam. The

Vietnamese are cell phone crazy, and one company is ailing and another is seek-

ing to take it over. In a dispatch from Hanoi, no less, a Mr. Thach (I didn’t get his

full Government title) vehemently opposed the takeover as “anti-competitive”,

and he strongly urged that even to countenance a takeover would not be “in the

long term interests” of Vietnam. Mr. Thach’s position was heartily endorsed by

several other Government worthies—was I in a communist country or a Univer-

sity of Chicago Law School antitrust class? Sure the paper’s mindless reporting

of Italian Soccer League scores was of some interest, but I began to think that

1975 wasn’t the only major date in this country’s history, and that 1990 was

A Step Back In Time

Page 21

equally or more important. It warmed my heart to contemplate the barrels

of hydrochloric acid that an article like this must dump into the stomachs of

Hanoi’s Marxist ideologues—are there any left up there? It was more than

delicious to contemplate how they must choke on their morning coffee when

greeted each day by such news. Tell me please, who won? I decided to have a

chat with an individual I believed to be just such an ideologue.

In 1951, in two highly different academic astrospheres, Harvard’s Hannah

Arendt published The Origins of Totalitarianism, and Eric Hoffer (his academic

milieu was a caboose on a Western U.S. railroad) published, The True Believer.

Reduced to their absolutely basic theses, both come to the same conclusion: “if

you scratch a brown shirt (Nazi), you will find a beefsteak (Red).” The particular

intellect of “the true believer” inclines him toward absolutes, and inspires within

him a relentless drive to destroy the non-believers. Hoffer’s book is as relevant

to today’s media creation, the so-called “Arab Spring”, as it was to a very frosty

cold war which was soon to erupt in Korea. Arendt and Hoffer believe that the

revolutionary and counter-revolutionary have much in common, as their beliefs

spring from identical intellectual premises, but that each takes a different path in

the forest. I was soon to test this theory.

Four Pots of Tea with a Side of Versace

Lotus is a jewel of a shop on Dong Hoi, tucked among the behemoths of

Western materialism—the small shop sells nothing but revolutionary propagan-

da posters. Lotus is an experience not to be missed as the proprietor will gen-

erously spend hours tying each poster into Vietnamese history and detailing its

relevance to “the struggle”. My initial intent was to purchase some posters as

gifts for a disillusioned ’60s SDS friend—he was mad for a Giap poster—and a New

York female Rad of some notoriety, but the purchases were a secondary mission

to what I believed would be a little “revolutionary” tutorial.

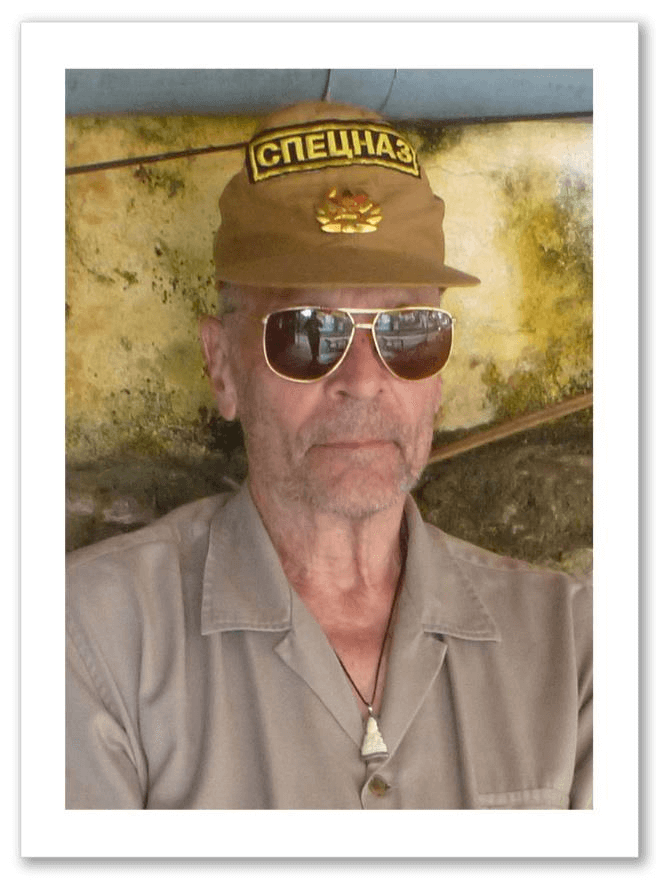

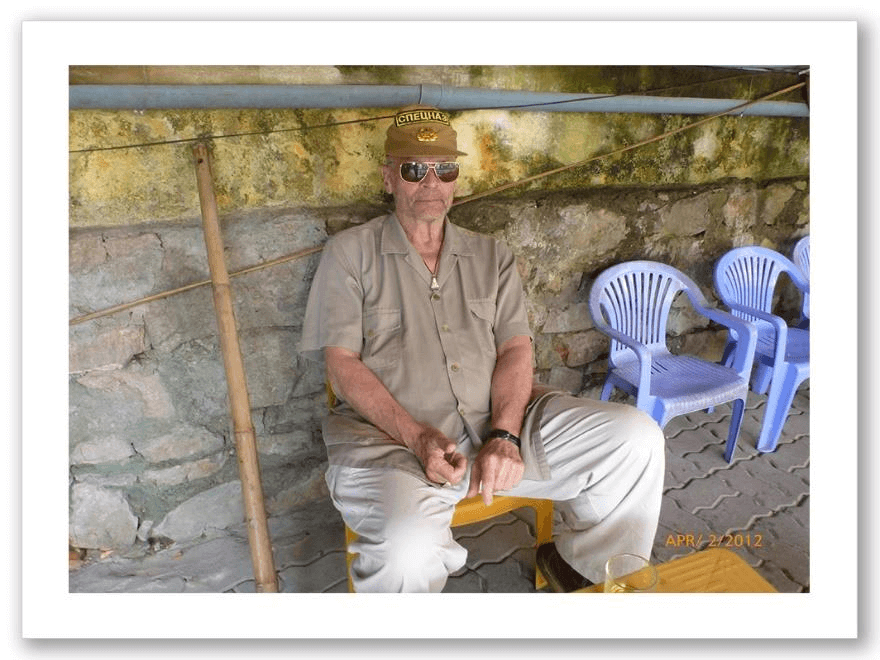

I armed myself with two pots of tea—one that vile green tea that almost

immediately tears the enamel off your teeth, and the other, good capitalist Tetley

black tea. I was dressed for the part in Ray-Bans, an NBO safari shirt and cargo

pants—into the fray.

The shopkeeper, whom I will refer to as “M”, (I use this designation to

protect the innocent) came to the door. I presented the tea and opened with,

“how do you like your new neighbors?” M replied, “Now we even allow big blue-

eyed men from the East into our shop, they are some of our best customers.” I

Page 22

A Step Back In Time

liked the retort and over the next four hours M graciously showed me the collec-

tion of posters, as we took an emotionally precarious journey over six decades of

Vietnamese revolutionary history.

I advised M of my total disillusionment with the Dong Hoi experience and

asked “Is this what 60,000 plus Americans died for?” Evenly, although such tact

was probably not called for, M answered “We lost millions.” I told M that I would

soon be walking on the trail where hundreds of thousands perished, and that it

was clear to me the “revolution” had been betrayed, and the Hanoi ideologues had

sold out. Deftly skirting the questions, M replied “nationalism is a great thing.”

I asked, looking out toward M’s neighbors, if the sight didn’t continuously

poison M’s thoughts. I got the same “Nationalism is a great thing” and “Why did

you arrogant Americans believe you had the right to dictate our form of govern-

ment?”—Touché! I slammed back—had M bought any lovely Tiffany charms

lately, the ones that cost six months of an average Vietnamese worker’s pay? I

offered to accompany M across the street to help with the selection—your move.

I had held back the Giap card and now I played it. Giap, perhaps the great-

est military man since Mao, [although his greatest triumph, Tet, was based on

Mao’s “Feint in the West (Khe Sanh), strike in the East (Tet)”] had recently and

very publically opposed bauxite strip-mining, stating such mining was inimical to

Vietnam’s national interest. This was much to the dismay of Hanoi bureaucrats,

and Giap had become a “non-person” à la Trotsky. I advised M that I was looking

for Giap shirts for my Rad and SDS friends. After some gentle prodding, M re-

plied that I would not find them in Saigon but maybe Quang Tri City, as “red roses

still bloom brightly there.” Nevertheless, M was able to dig up a Giap/Ho poster

which will bring joy to a bummed out SDS cadre. I thanked M for going the extra

mile and asked if there were any more Giap/Ho posters? I was told, with a little

smile, that they were scarce.

After consuming four pots of tea, it was time to leave, and I asked M, as

we stood now, who won the war? M indicated that in 1975 they did, and today,

given Dong Hoi Street, we did. Then M added that we, you and I, both lost, but

that at least I did not have to walk to work every day past Versace, et al. I told

M I walked to work every day on Wall Street, and that I waltzed every day with

moral indifference in America. Sadly, during my four hours with M no other cus-

tomers arrived. I bought some additional posters and left the shop secure in the

knowledge that Arendt’s and Hoffer’s theories were alive and well. I never spent

a better four hours with a dyed in the wool ideological adversary.

A Step Back In Time

Page 23

“Has Anybody Seen General Giap?”

I decided to hire a driver and motor scooter to search for a talisman for the

trip and to recondo for Giap T-shirts. This is no small decision as it is best not to

get a driver who is too cautious. As I spoke no Vietnamese, it was a crap shoot,

and I won. My driver’s initial “grand ges-

ture” was to go four blocks against traffic to

make a left hand turn—returning a cowboy

back to the Ben Thanh market.

Before leaving the U.S. I was told by

a Vietnamese client that I would be disap-

pointed by the market, price-wise and in

terms of selection—he got that right! We

searched in vain for Giap T-shirts—when we

asked, we were greeted by stares reminis-

cent of a Stalinist Central Committee meet-

ing considering the Trotsky issue—some

professed not to know him, even when my

driver colleague queried them in Vietnam-

ese—we were shopping for an image of a

non-person. Traditional crafts such as lac-

quer were reduced to one stall, talismans

and hill tribe fabrics were nowhere to be

found. By chance I was able to convince a seller to string a small Buddha on a

Page 24

A Step Back In Time

brown leather cord, which I prominently displayed from that day forward.

Otherwise I could have been, except for the tea and coffee, in a cut-rate Ameri-

can clothing store—rubbish.

I then travelled to Cholon to review old acquaintances and it, too, now

looks like a California strip mall. We canvassed both the Binh Tay and An Dong

markets in search of Giap T-shirts. If you want to see private enterprise in its

rawest form, sit yourself outside the Binh Tay market and watch the “sweat

shop” action. Human beings as beasts of burden, à la the Singapore docks in the

1950s. It is a great advertisement for unionism! No Giap, no traditional crafts.

Back to the hotel veranda, another Coke, malevolent thoughts for the construc-

tion site—well into the night—solo—no friendly spirits. Tomorrow: back into

the fray.

Seeking Out the Spirit of Saigon

Religiously, without fail, upon our return to Saigon, Micheline Anne would

take us to the Jade Pagoda and give thanks for our safe return. Given what had

happened in my early life, I

was never too fired up about

this ritual trip, but I thought I

had to go back to get closer to

her memory—wrong.

The place was jammed

and the cash registers were

singing. I sat down and

watched the “action” and, to

my mind, if Luther were to

come back to earth and land

here with a small chainsaw

the place would be match-

sticks in minutes. Supplicants, paying fistfuls of money to keep the oil going for

the lamps, and the air thick with incense. I am not knocking incense, but how

does a spirit sort out whose incense is whose? I sat there quietly, a relative term,

with the hordes seeking benefits. I waited patiently, hoping there would be a

seventh inning stretch—there was none. I watched the hustle, and I use that

term in the street sense, and sadly reached the conclusion that if Micheline

Anne’s spirit were to be found, this was not the place. I lit my handful of joss

A Step Back In Time

Page 25

sticks, made my way out of the sanctuary, and was greeted by an altar that

captured it all for me.

Giving a new meaning to “pay your way into heaven”, the altar is guarded

by its own steel safe. I sat down to watch and see if you prayed first then paid,

paid first then prayed, or applied for

spiritual Medicaid. Leaving aside the

cynical nature of my voyeurism, the

results were quite startling—capitalism

and bourgeois morality ruled, as all but

three worshippers paid first. But I was

pleased to note the three who took the low

road. If you want to get in touch with the

spirit world in this place, bring lots of

dong, because if you spend even a few

moments watching “the action” Marx’s

“opiate of the masses” springs readily to

mind. Micheline Anne and I will meet in

some tranquil spot—this did not even

remotely approach such a spot. The Jade

Pagoda has none of the tranquility of Lao,

Japanese or Burmese temples. It is an

Japanese or Burmese temples. It is an

oil-burning, money-making spiritual

casino with not the slightest hope of a

payout—no solace.

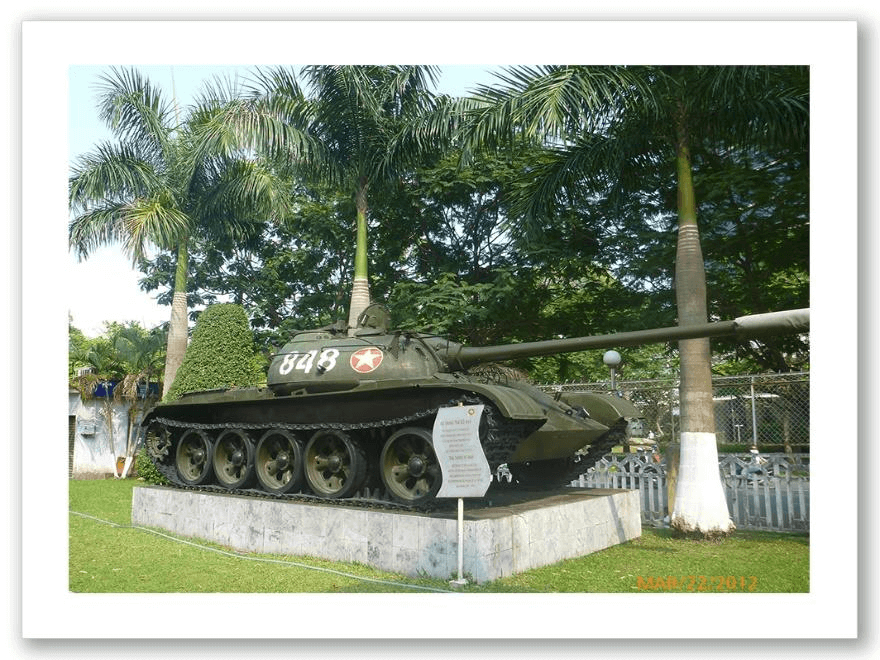

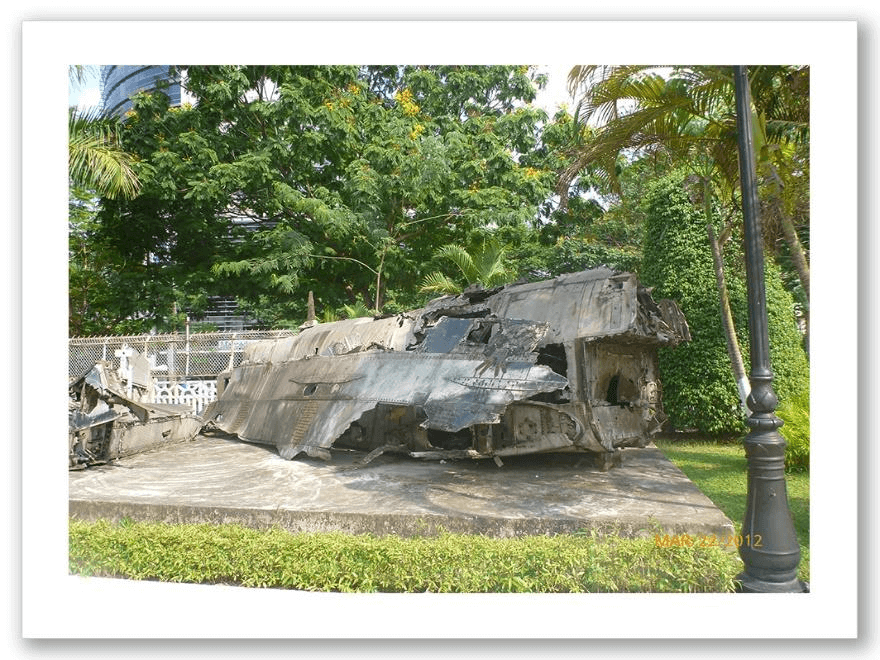

I decided to head away from the

madding crowd and hit the Military Mu-

seum. The trip was interesting, on a very

modern road, old structures juxtaposed

with new high rise apartment buildings.

I arrived at the entrance where I

was greeted by two neatly dressed high

school age guardians of the revolution-

ary flame. She, I noted, was studying

advanced algebra and he quantum

physics—both books in English. I was

escorted into two cavernous halls which

Page 26

A Step Back In Time

meticulously detailed the NVA’s ’73 and ’75 campaigns. I was politely asked if I

wished to be escorted as I toured the exhibits. I declined the invitation, but asked

if there were any additional visitors that day; there were none.

The halls were huge,

The halls were huge,

with military maps detailing

the developing events, and

numerous small machines of

death everywhere; the big

machines of death were out-

side. As is my wont, I decided

to explore the building, and

the next room I entered was

a large banquet hall that was

beautifully decked out in

white for a wedding to be held

that evening. Much hustle

and bustle setting up for what I guessed to be a wedding for 400 “intimate”

friends. Despite my recent strange interlude of l’amour fou, I decided to investi-

gate. As is the custom at Vietnamese weddings, pictures of the bride and groom

were prominently displayed. She, youngish and your basic ten-star knockout, he

considerably longer in the tooth, jowly, with triglycerides on fire—a match made

in heaven.

in heaven.

It was the seating that

got me. Chairs were lined up

in rows of thirty—no tables.

Now, I have been led to believe

that weddings provide fertile

ground for wolves of both

sexes to prowl. How do you

prowl when the object of your

desire is in Seat 24 and you

are in Seat 2? Despite recent

personal setbacks, I am still a

believer à la Robert Browning

and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s initial encounter; here, alas, there was little

chance for potential lovers’ eyes to lock over the Gruyere. An invitation, no

A Step Back In Time

Page 27

matter how subtly nuanced, to view the ’73 Highlands campaign, or perhaps in

the next room the ’75 Highlands campaign, hardly strikes a romantic chord. A

coquettish suggestion to take

coquettish suggestion to take

a moonlight stroll amidst nu-

merous machines of death—

planes, tanks, and B-52 wreck-

age—leaves a great deal to be

desired romantically, with the

possible exception of a chance

to steal a kiss in the shadow of

the clearly erotic SA-2.

Although not able to

attend, I wished the couple and

their guests, as they hike the

romantic trails of life, well.

A little down from the

A little down from the

museum I treated myself and

the driver to warm Cokes and

contemplated “the meaning of

it all.” L’amour fou is such a

ludicrous concept; the game is

fixed from the start.

I returned to the Contin-

ental, got another Coke, and

sat on the veranda. Across the

way in front of the opera house,

actors in traditional ancient

costume posed for tourists and

were much the rage. It struck me that they also did this fifty years ago to attract

patrons to the evening’s performance. The actors worked hard for two hours, but

I noted that none of the tourists proceeded to the box office to purchase tickets.

As the sky grew dark I attempted to get into the construction site but with-

out success as the site was guarded. Another evening of increasingly malevolent

thoughts as I sat on the veranda. The hotel people were great. They left my table

but put away all the others. Empathy, or afraid I might go off? I walked to the

flower market, purchased eleven yellow roses (my calling card), returned to the

Page 28

A Step Back In Time

site, estimated where Micheline Anne had fallen, laid the roses there, and spent

the remainder of the night guarding them until I went upstairs to pack. When I

came down at 04:30 the roses were still there—inadequate and terribly sad, but

the best I could do.

I had an 0 dark thirty flight to Hue. When I arrived at the domestic ter-

minal things were a bit slow so I had tea and a roll. I moved to a seating area

and, strangely, saw my server running after me. Explaining I had overpaid she

handed me a 200 dong note (10 cents). I estimated she left her post and ran 200

feet—behavior that is far from the norm in the U.S. When I thanked her I hoped

she was as touched as I was by her gesture.

I read in the morning’s Saigon Post that Viet Nam was experiencing an

economic downturn. You could not divine this from the domestic terminal, which

was soon jammed wall-to-wall and out the door. My dawn patrol flight to Hue was

chock-a-block full, and I was the only roundeye.

As we taxied out I saw an example of capitalism at work that I had noted

while waiting for my flight: numerous domestic airlines bearing exotic names

had sprung up. One of these “exotics” was on a different runway and the aircraft

was clearly a DC-9—what model I could not make out—the mists of history dim

the senses. I made a mental note never to fly that airline. Better to walk in.

Air Vietnam to Hue at Dawn

The flight to Hue was interesting as we played dodge ball with thunder

heads up to 35,000 feet—beautifully ominous, because if it started to rain it would

rain for days. Landed without incident, and where the ride into Saigon had been

a free enterprise eye-opener, the ride into Hue was just the opposite. Early in the

morning, little traffic—architecture crumbling French with some Stalinist accent

pieces.

We pass some small shops starting to open, but no people shopping. A tell-

ing point about the city: the taxi driver drove the speed limit and barely honked

the horn. None of the Saigon motorcycle hordes in evidence, a slow downtown. I

liked it already.

I was staying at La Residence. If you can, don’t miss it. The former Gov-

ernor General’s home, and it merits all five of the stars given by the Vietnamese

Travel Bureau—a jewel, staffed by gems.

A Step Back In Time

Page 29

I had previously corresponded with the hotel’s travel director and I made

a beeline to meet him. You would have thought I was the prodigal son returned.

He immediately expressed, and for the next two days constantly reiterated, his

grave concern about the

grave concern about the

“walkabout”. He shut down

his desk, and we adjourned

to a café next door; this café

was to have a major impact

on my stay in Hue. The travel

director and I sat down, and I

engaged in a “self-criticism”

struggle with him about my

plans. He soon understood

my reasoning.

I have a spiritual aver-

sion to being charged five

dollars for a can of Coke or a bag of M&M’s. I found out I could buy a can of Coke

at this café for fifty cents. Also, I was put off by the way Vietnamese treat their

lotto sellers. Sure, everyone knows the lotto is fixed and crooked, but these kind,

elderly women are gentle souls, living a marginal existence and, unlike beggars

in other cultures, never aggressive. It torqued me to see them waved off with a

disdainful flip of the right hand, or worse, completely ignored. I decided to do

something about it. I quickly noted that the café was quite exclusive. In fact,

two other parties sitting five feet from each other barely spoke. Not a word ex-

changed as one passed a newspaper to the other.

Welcome to “Harry’s”

The next lotto seller came by. I immediately bought two dollars’ worth of

lotto tickets, invited her to sit down with us, ordered a Coke and handed the lotto

tickets to the proprietor—an unprecedented occurrence I am sure. The joint was

now mine, and I named it “Harry’s”. While in Hue I made it my headquarters

and over the three days following my “good luck” gift to the proprietor I received

oceans of free black tea. There is something so delicious when a club manager

knows what you drink and what your guests, three lotto sellers, drink—Cokes all

around. A new blow for American capitalism. The atmosphere in Harry’s was

Page 30

A Step Back In Time

peaceful, relaxing, and on a subsequent

peaceful, relaxing, and on a subsequent

visit I jealously guarded the panache of

the club. The old women and I could not

communicate with each other, so we sat

in companionable silence, taking a load

off, and contemplating “the meaning of

it all.” Sadly, it could not last forever. I

reminded myself that when I return

I must bring some Bach, Beethoven,

Mozart, and Wagner’s “Overture to the

Flying Dutchman.” This will put us well

ahead of the pack musically; he who

controls the velvet rope sets the tone.

Harry’s was to provide another

personal highlight of the trip. Way back

in the ’50s I became enamored of a style

of Chinese scroll painting I called “karst

painting.” At the time I believed the scenes were all in the artist’s head. I was

wrong, but it took about forty years to correct my misinterpretation.

I had mentioned karst painting to a client’s brother and he set me straight

by inviting me to join him on a trip to Guilin on the Li Jang River—a more than

moving experience provided

moving experience provided

by a man who even in defeat

knew victory. After coming

off the river the client’s

brother and I repaired to a

piano bar at a Holiday Inn

where a most enjoyable

tuxedo-clad piano player

entertained the two of us.

Still on a high from the river,

I noted the pianist playing

many romantic songs in a

very distinct style, including

a song which would turn out to be Richard Clayderman’s “Murmures.” I asked

him to play it again and I was on a roll: champagne—two bottles—for the pianist

A Step Back In Time

Page 31

and my client’s brother. I don’t drink, but I have been told they thought it was a

great party. Richard Clayderman touched my romantic soul.

While at Harry’s on the evening of the third day, I heard a Clayderman

song and asked the owner to play it again, and he did. When it finished, the

owner, who spoke no English, handed me the disc and said “un souvenir pour

vous.” I politely declined but the moment will never be forgotten.

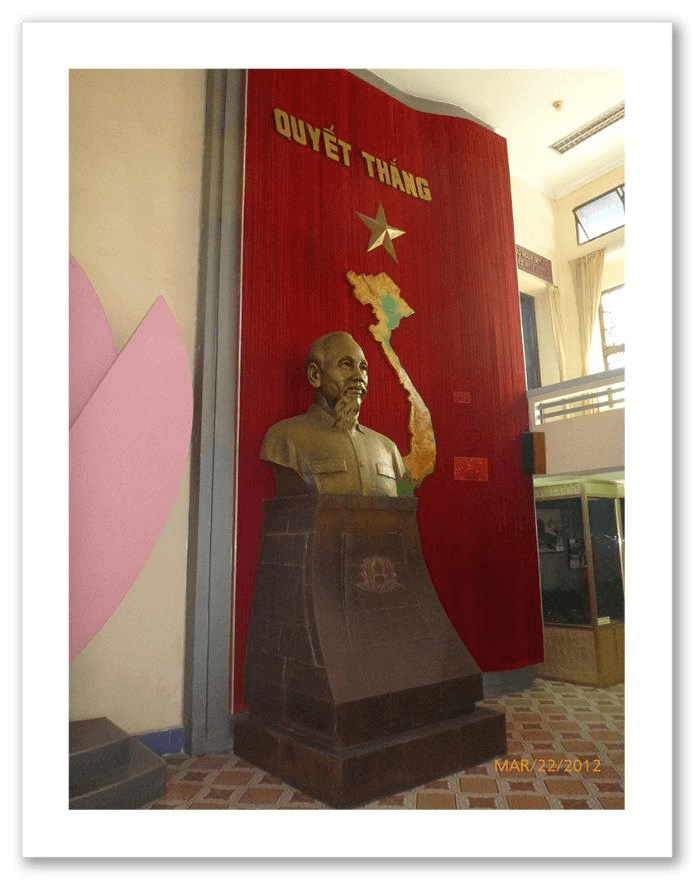

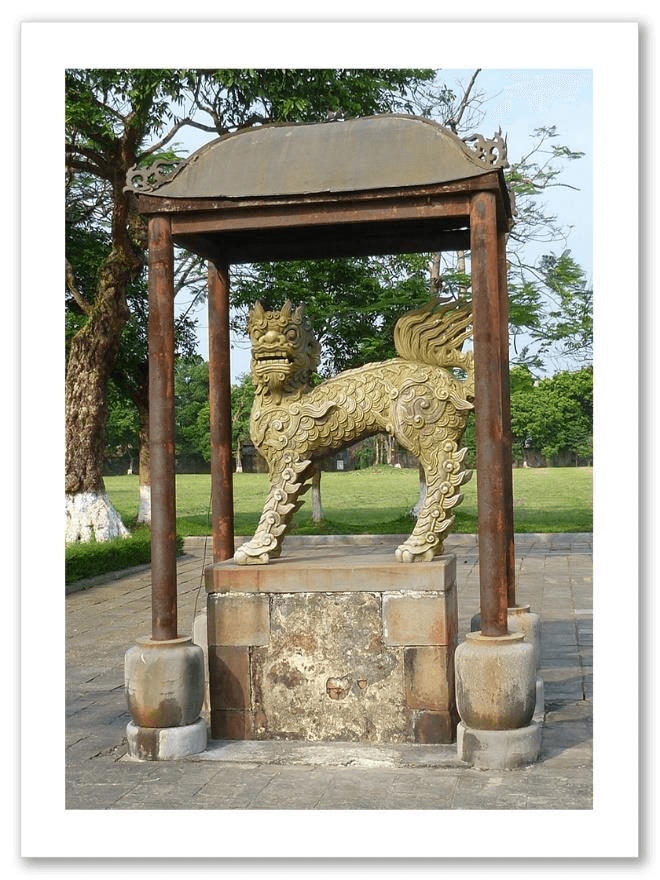

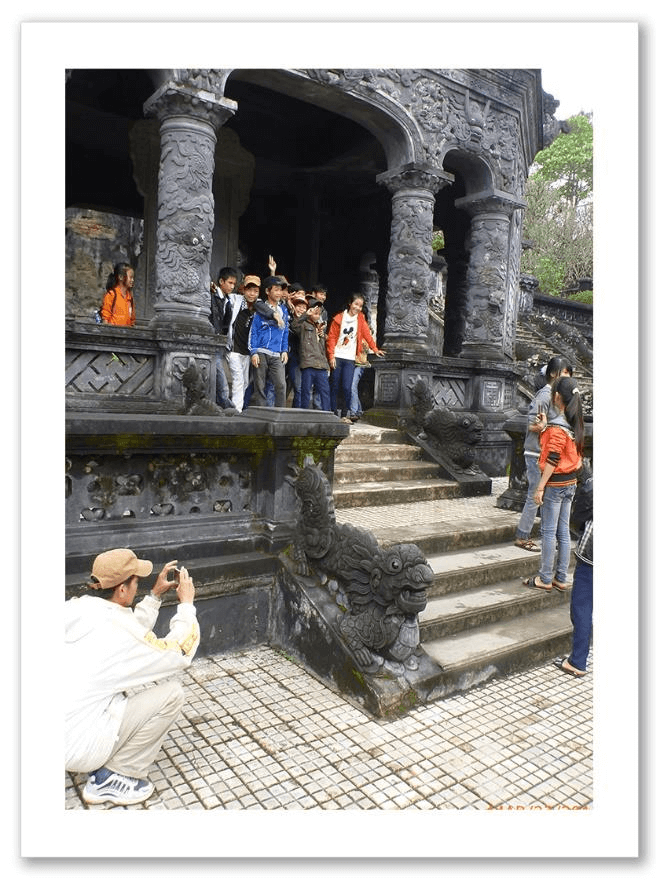

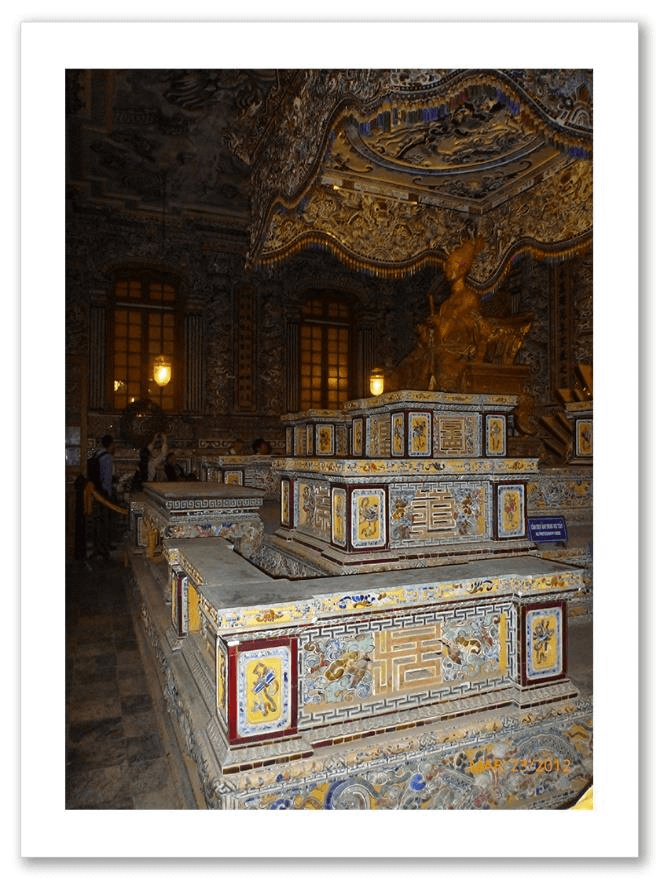

“The Imperial City of Hue,” the former royal capital of Vietnam, had been

a seat of learning and the arts. During the war it was captured by the Viet Cong,

and 6,000 inhabitants, who had been selected for liquidation prior to its fall, were

murdered. For several weeks Hue held out, despite continuous air assault which

pretty much leveled the city. The Viet Cong flag flew over the citadel and was a

continuous target for the besiegers to knock down. I once saw a T-shirt for a

mortar crew which showed a 91mm mortar with the caption “We are into earth-

moving and instant urban renewal.” We pounded it non-stop, but never com-

pletely succeeded in knocking the flag down. The psychological point was made

and is still being made today.

The city was going nowhere and falling into decay until 1990 when some-

body recognized that tourism could bring it back. Whatever your political

persuasion the promoters

persuasion the promoters

have clearly done a good job,

particularly with the wind

machine that blows the flag

(half a football field in length)

that flies over the citadel day

and night. Before I toured

the citadel I wanted to walk

around it. This was great fun

because the fortress is sur-

rounded by an impenetrable

fence of small enterprise

shops selling everything—

clothing, electronics, even a Viet Cong flag, which I immediately scooped up for

my SDS friend.

I returned to Harry’s for an evening with Richard Clayderman—it does not

get much better than this! Clearly Hue exhibits a cachet that Saigon might have

done well to consider, but unfortunately it is now too late, as Saigon has gone too

Page 32

A Step Back In Time

far down the Lotus and Lamborghini path to turn back. Vulgar materialism has

not, for a multitude of reasons I suspect, overwhelmed Hue. Not such a bad thing

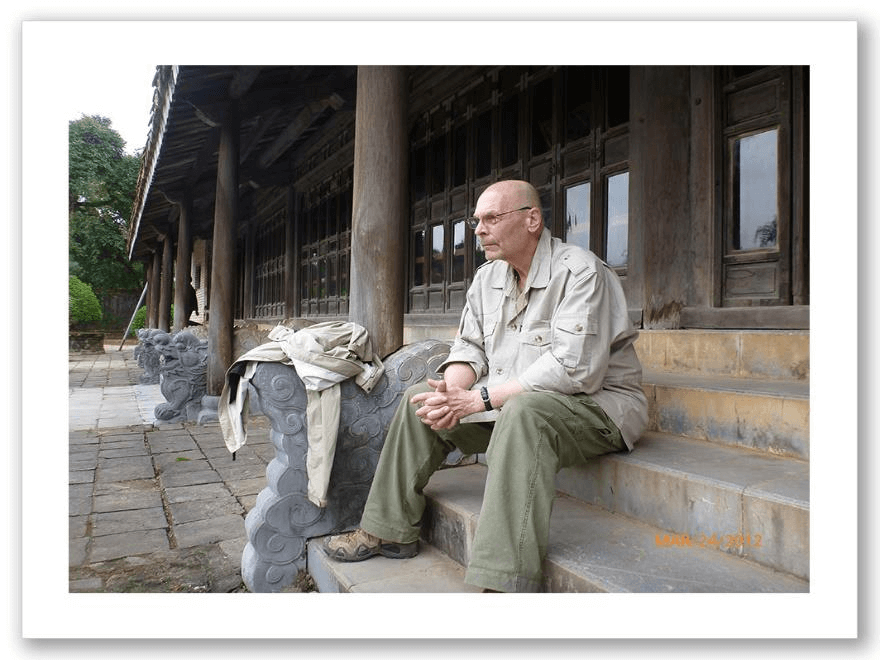

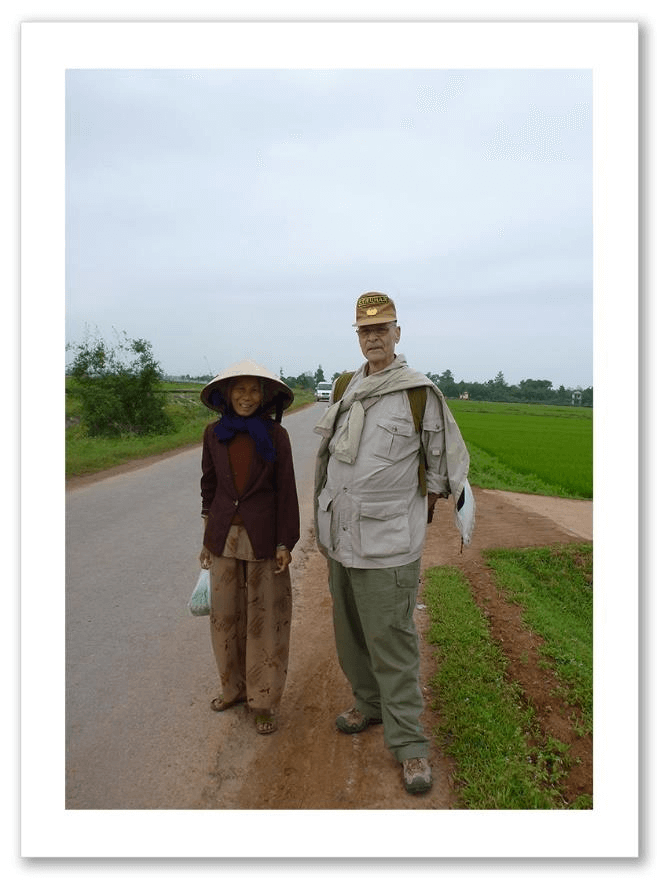

to live in a less materialistic backwater.