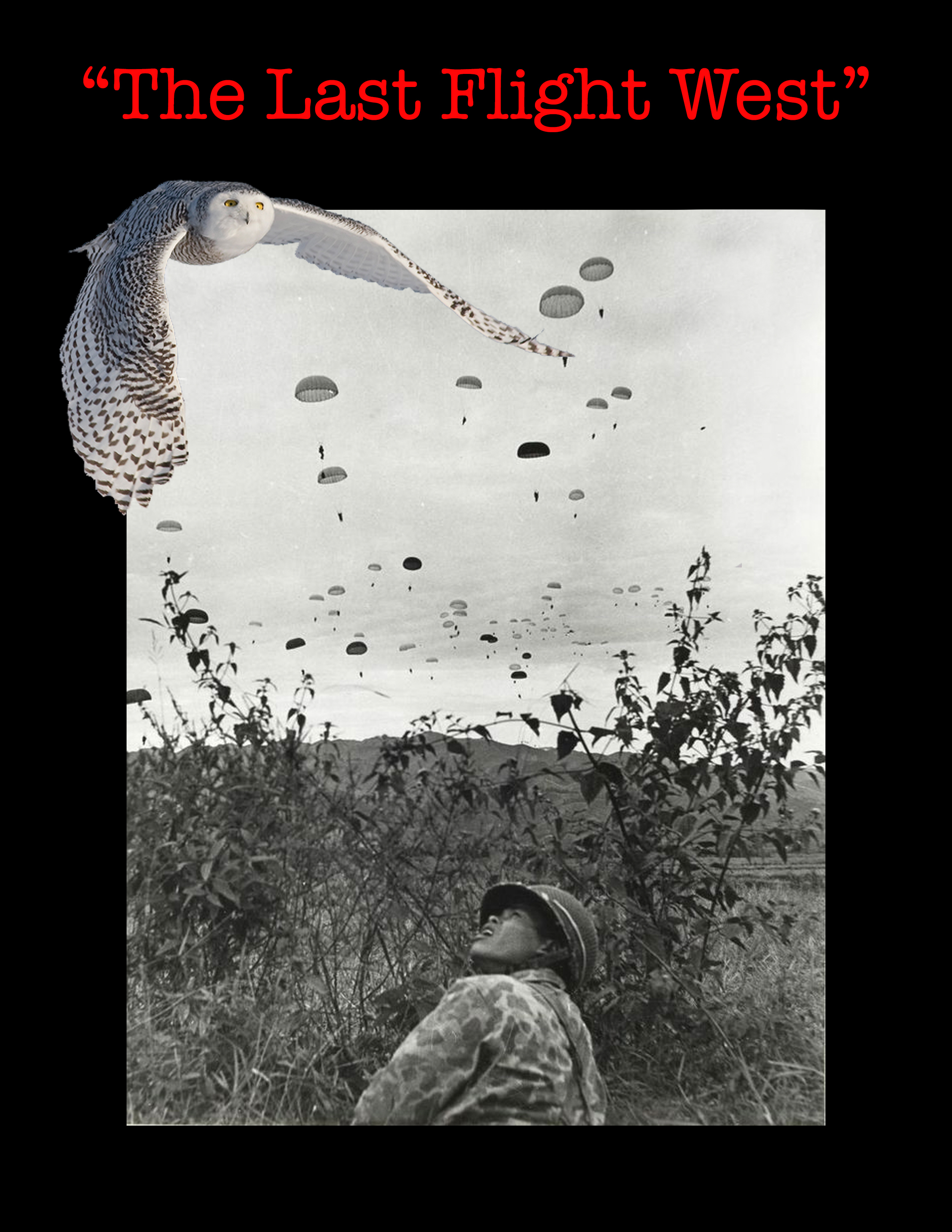

THE LAST FLIGHT WEST

THE LAST FLIGHT WEST

IF THEY ARE TRANSFERRED TO THE HA GIANG AREA AND STAY A WHILE

THEY COME BACK MUCH CHANGED, SOME NOT EVEN DRINKING WINE.

Anonymous French Foreign Legion Officer

1936

IF YOU ARE TOLD YOU HAVE BUT A LITTLE TIME TO LIVE, GO TO A

DANGEROUS AND EXOTIC PLACE AND WALTZ WITH DEATH. SHE WILL SEE

YOUR JOY AND EMBRACE YOU BEFORE THE BAND STOPS PLAYING—YOU WIN!

Harry C. Batchelder, Jr.

Ha Giang, Vietnam

2014

© 2016 Harry C. Batchelder, Jr.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

-

Cancer Dreams and Nightmares • Travel Plans

-

Air Vietnam to Hanoi • A Late Night Arrival

-

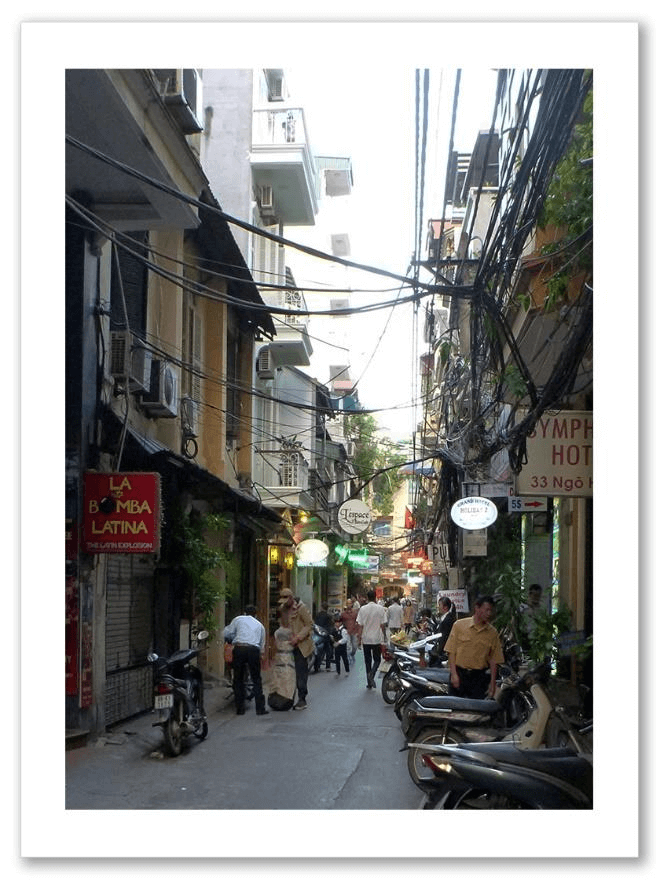

A Shrill Awakening • Walking the Hanoi Streets • The Pole Sellers

-

Comrade Stone • “Red Rage” • Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum

Graduation Day • The Ao Dai • Hanoi Shopping -

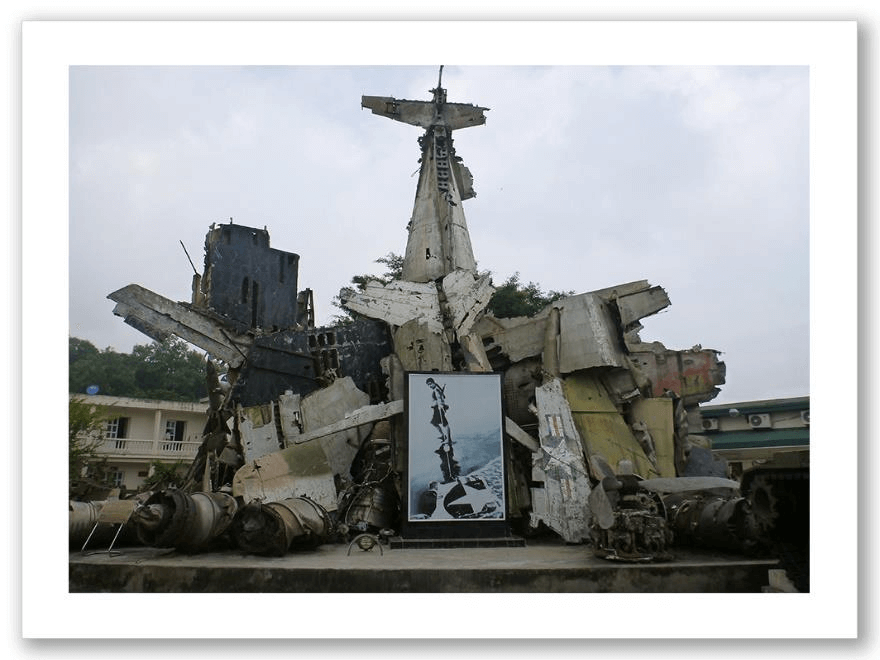

B52 in the Lake • Air Military Museum • Metropole Veranda

Hanoi Brides • Motorbike Lesson I -

Cockfight in the Park • Pholing Temple • Glace Vanilla

One Pillar Pagoda • Motorbike Lesson II • Plan D -

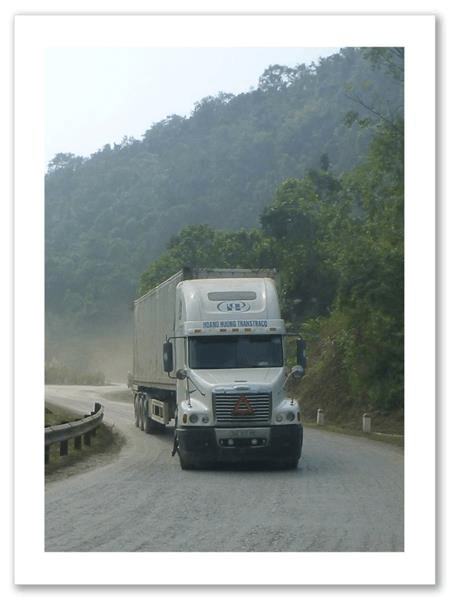

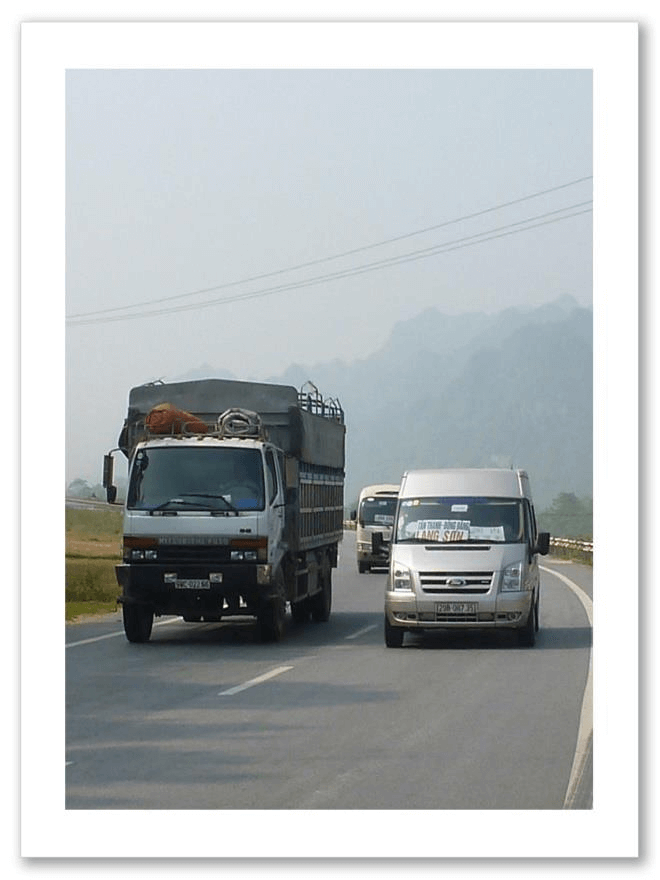

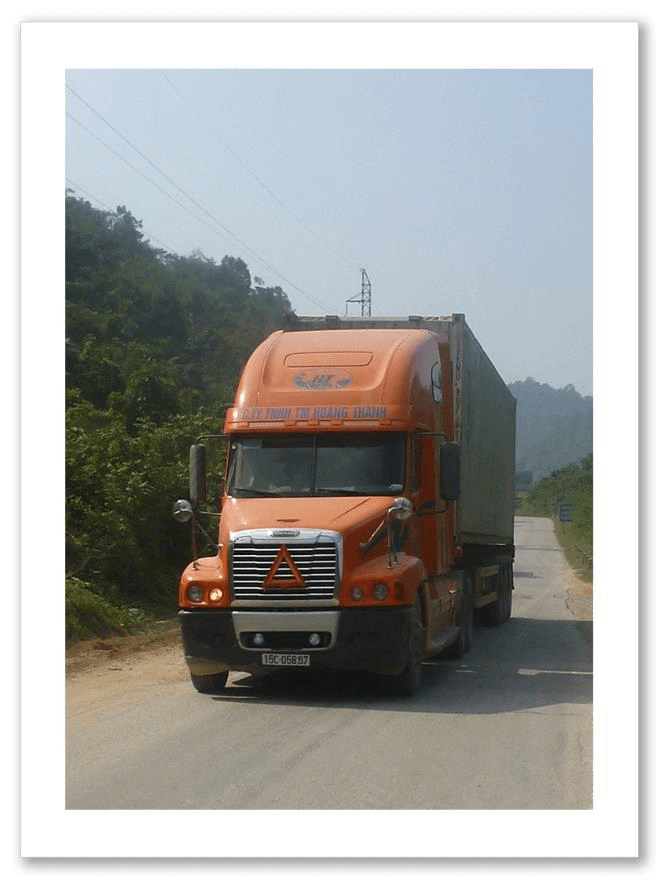

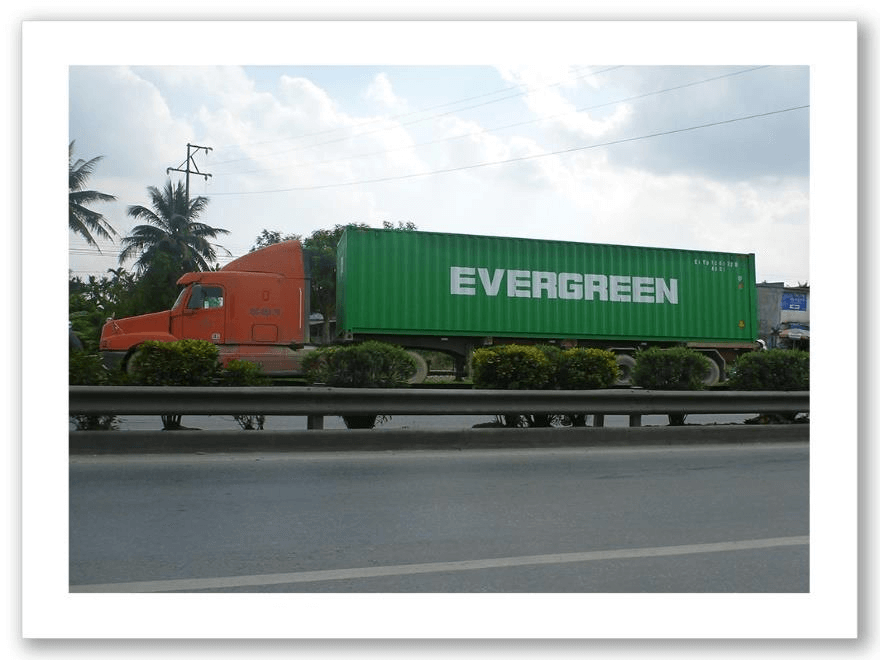

An Early Start • “Just Hold On” • Traffic and Trucks

“Princess of the Mists” • Pulling Rank in Mai Chau

Lady Monks and California Seekers -

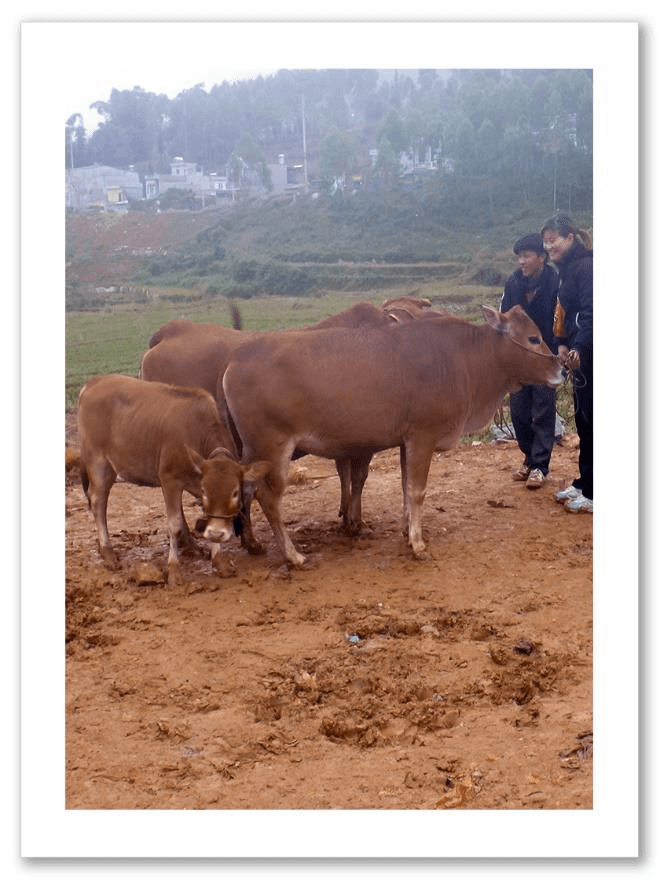

The Road to Dien Bien Phu • Seductive Scenery • Holstein Cows

Vietnamese Yogurt -

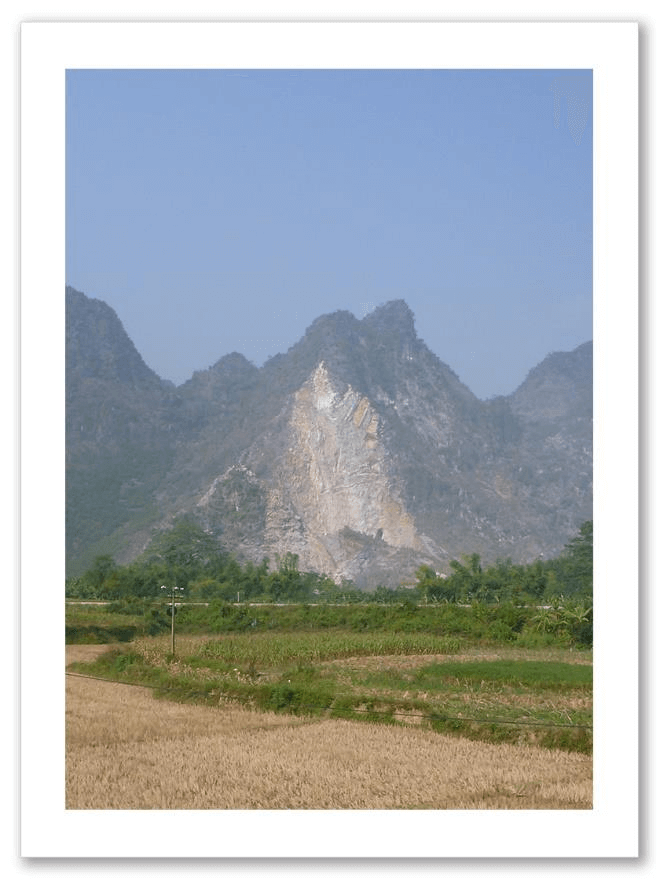

“Golden BeeBees” • Pha Din Pass • Up-Country Scenes

Pressing On to Dien Bien Phu -

Dien Bien Phu • A Huge Letdown • Eliane • Windows Café

Castrie’s Bunker -

The Victory Museum • A Battlefield Beyond Reclamation

A Tourist Trap Siege -

The Blue Tents • Dust and Mud • Muong Lay is Doomed

The Towel • Ghost Hotel on the Mountain

– i –

-

Breakfast with Ghosts • Lai Chau • Red Rage Takes a Pounding

Tan Tron Pass • On to Sapa -

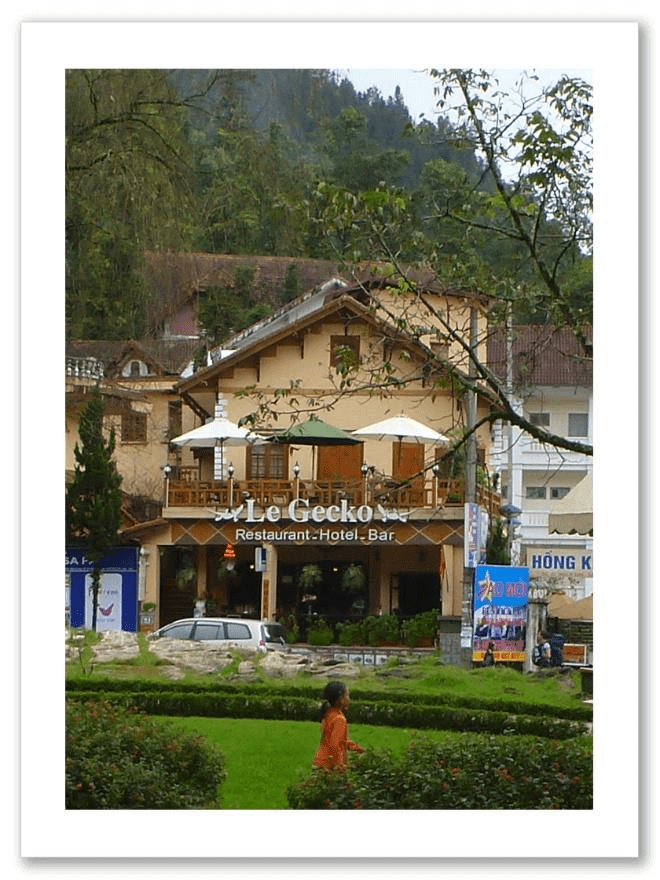

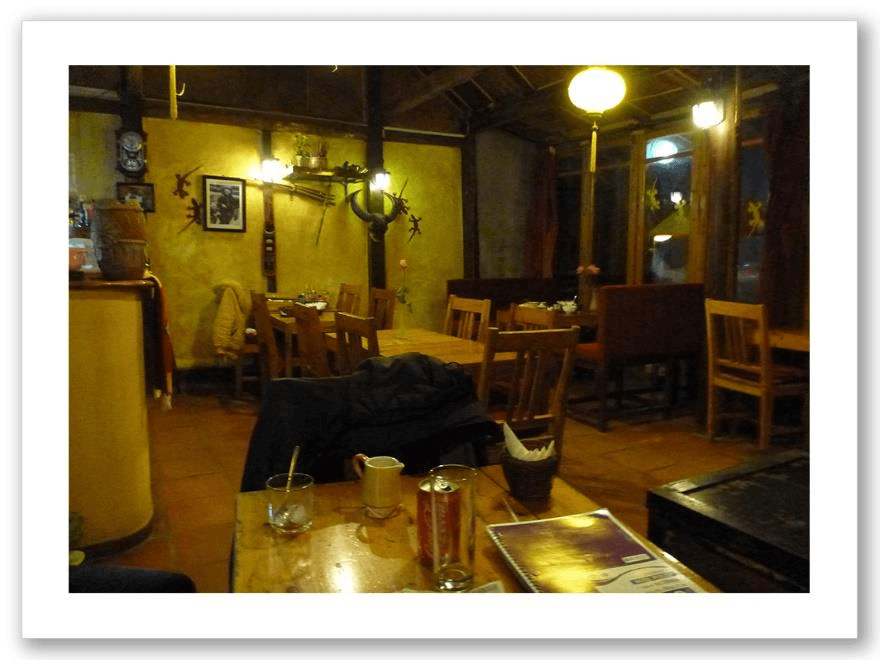

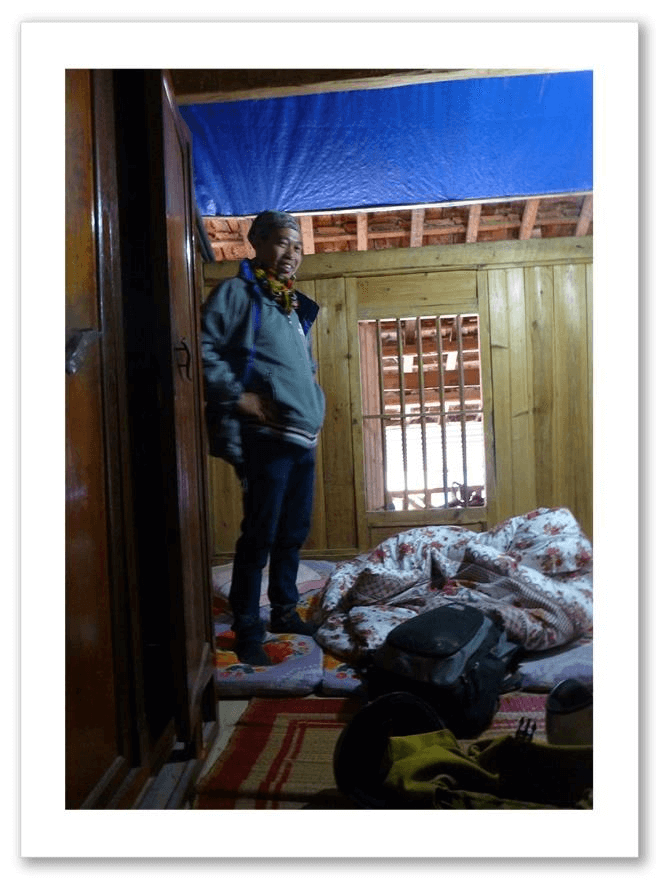

Into Sapa • H’Mong “Home Stay” • The Petit Gecko

The Obligatory BMW -

Back to The Petit Gecko • Return of the “Home Stay” Tourists

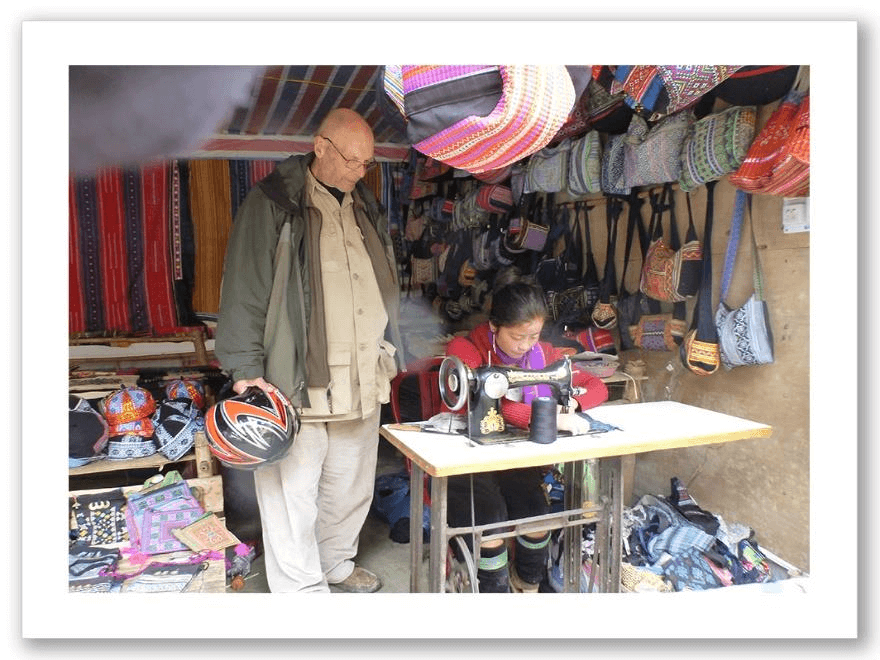

The Artist’s Café • Flower H’Mong Embroidery -

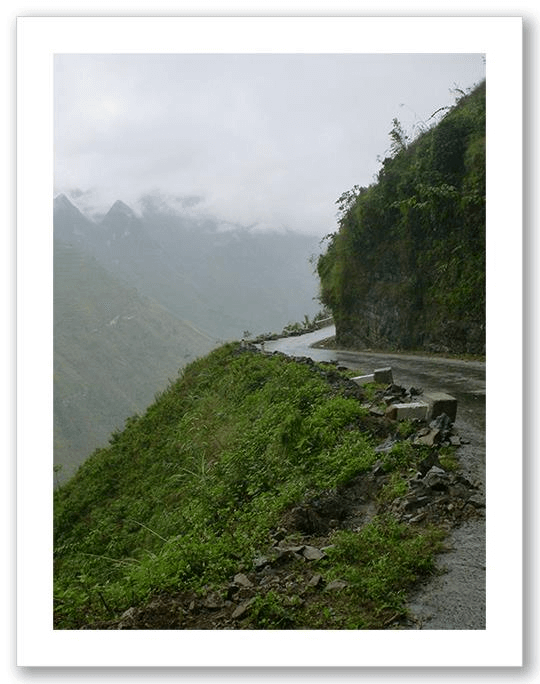

Leaving Sapa • Bad Roads • Peasant Convention • Night Driving

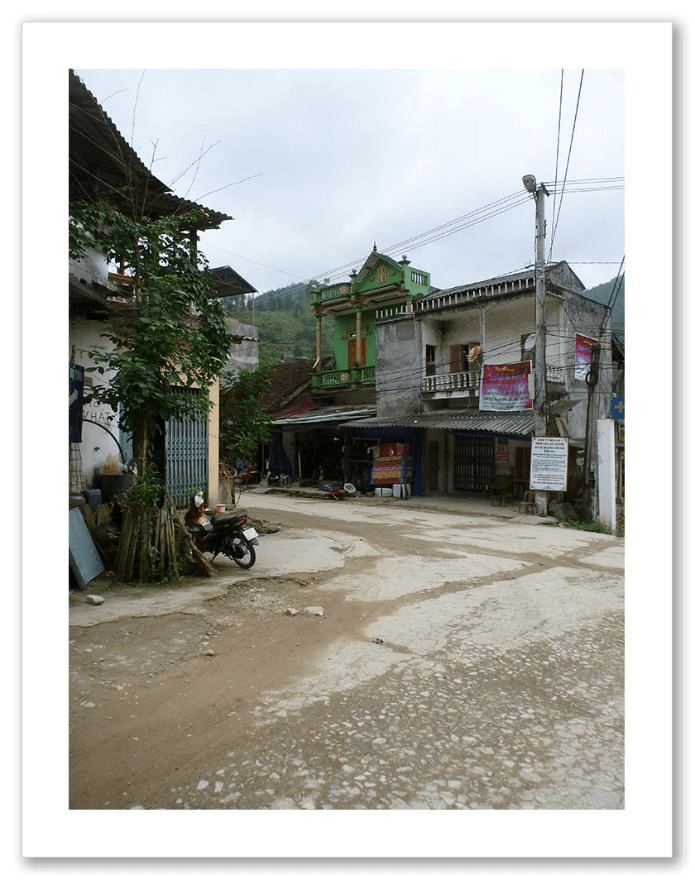

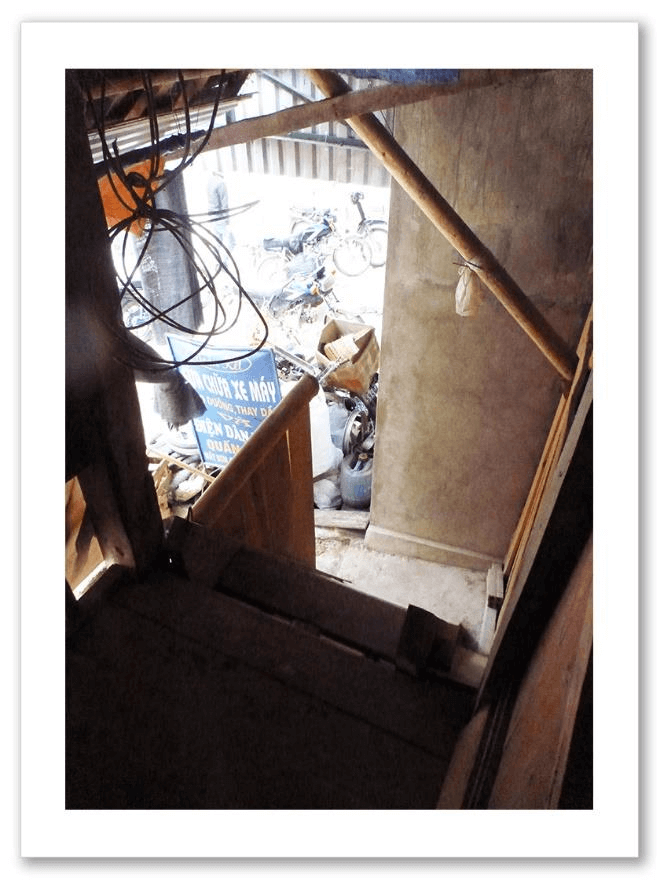

Pho Shop at the Crossroads • Attic Lodgings -

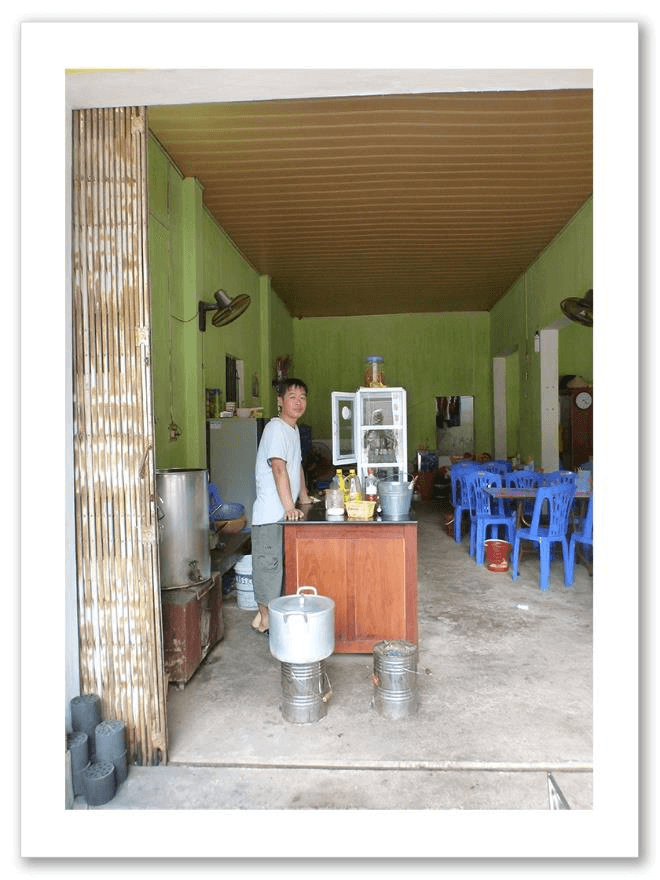

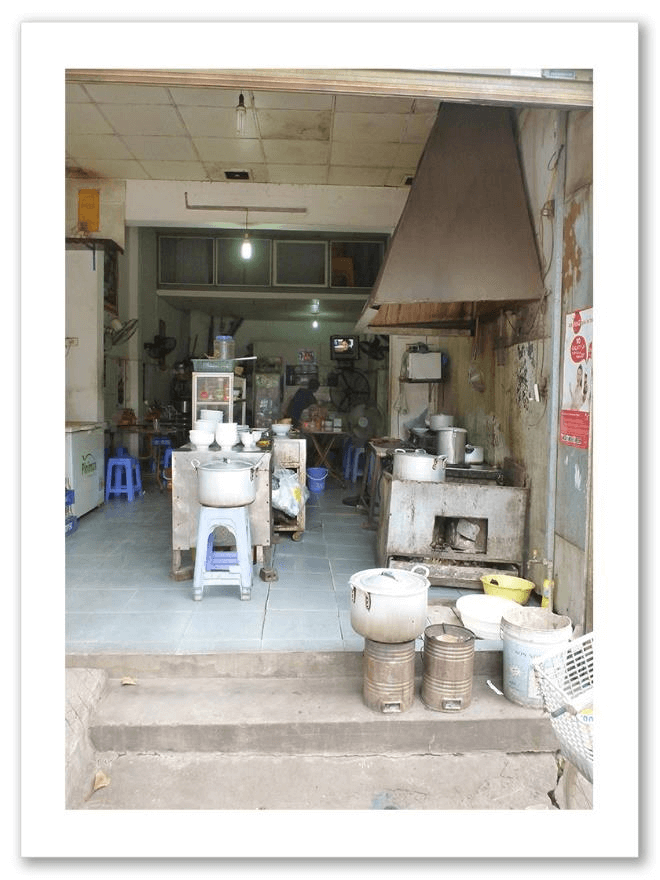

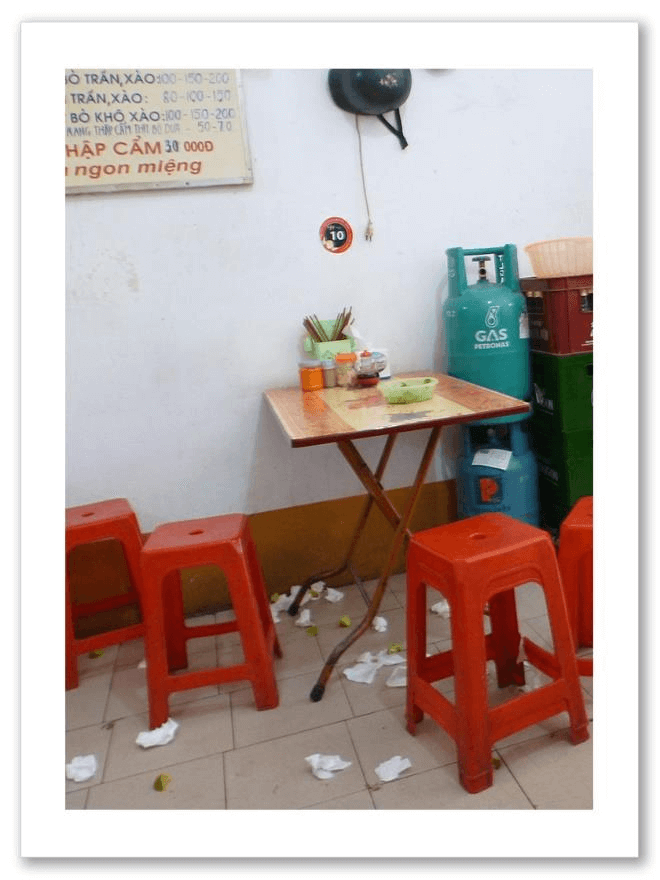

Pho Shops I Have Known

-

Impromptu Loo • Off to Ha Giang

-

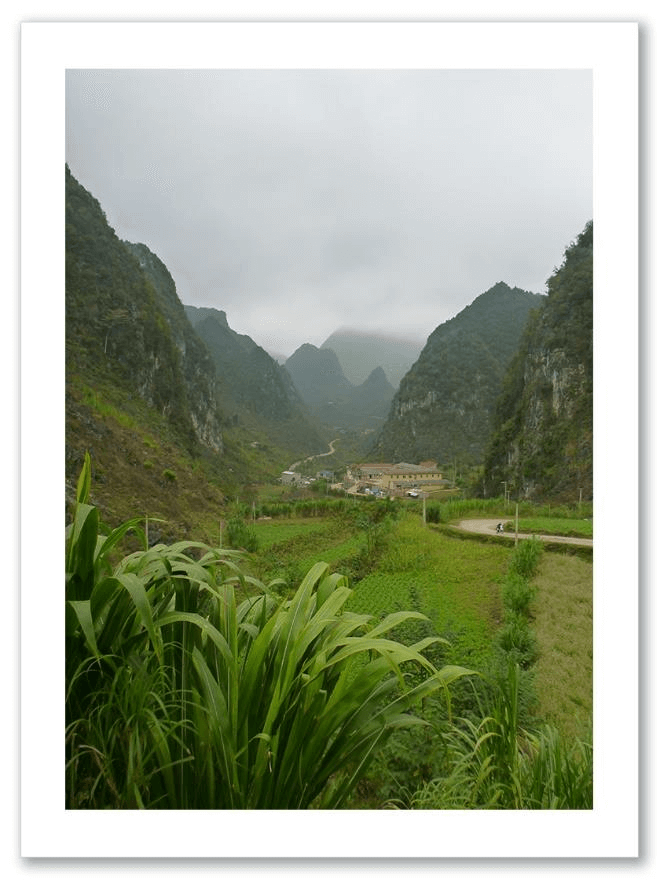

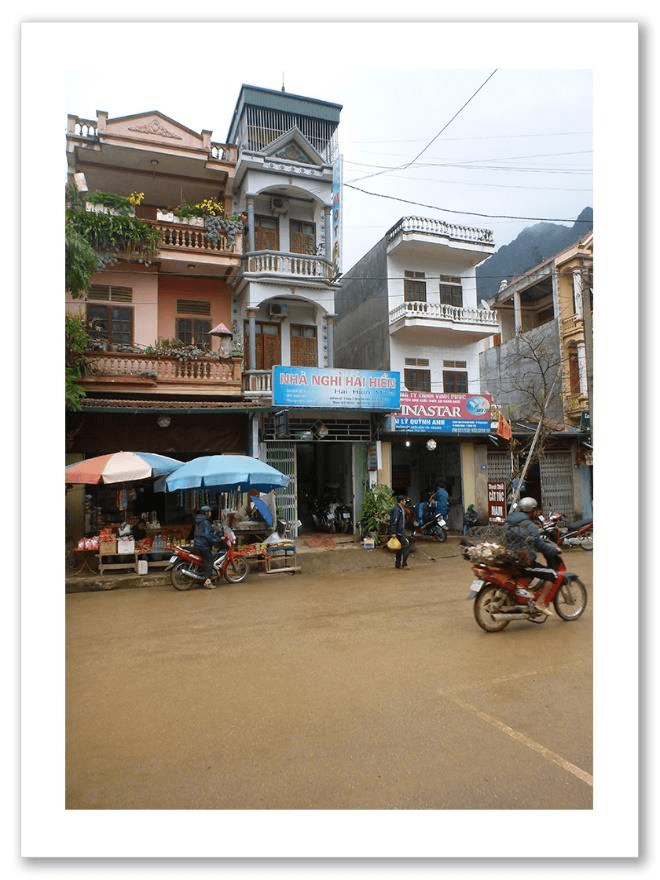

Misty Trip to Dong Van • Loofah Shopping • Teenage Pharmacist

-

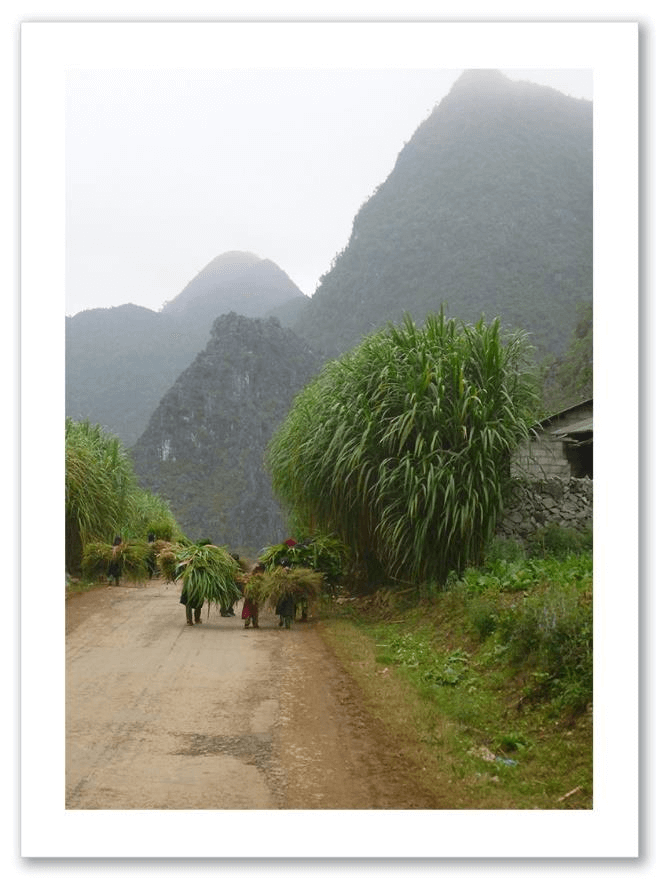

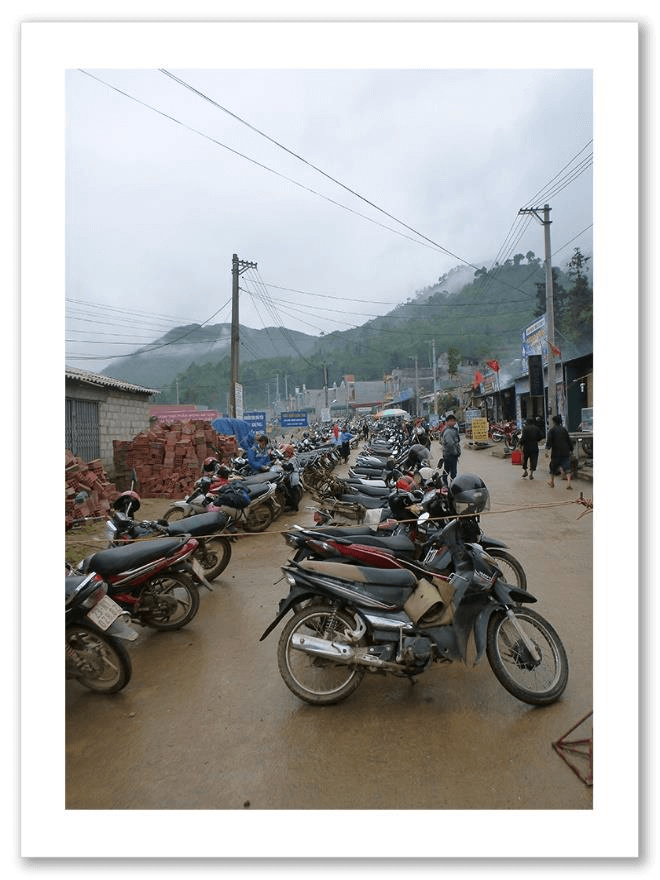

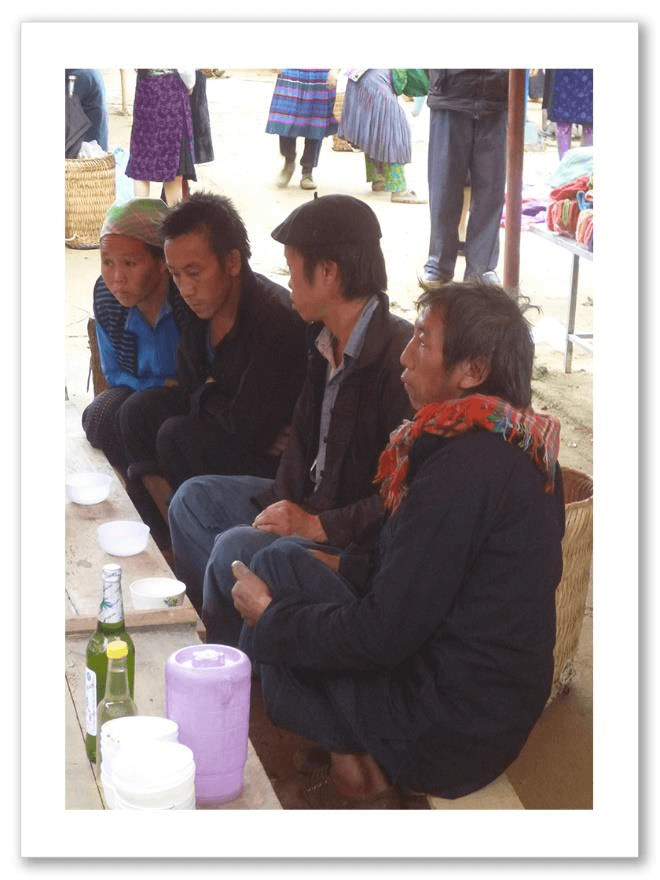

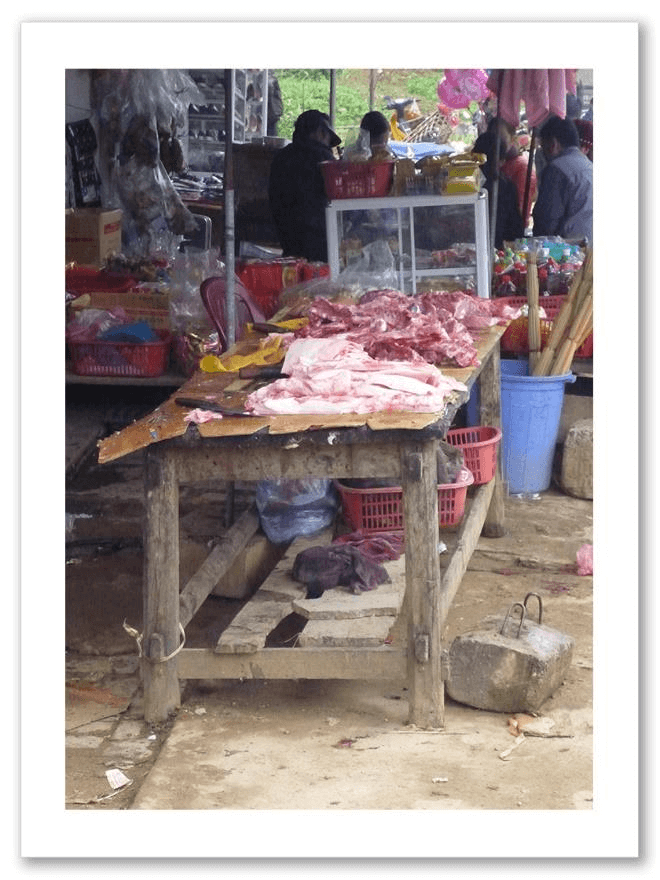

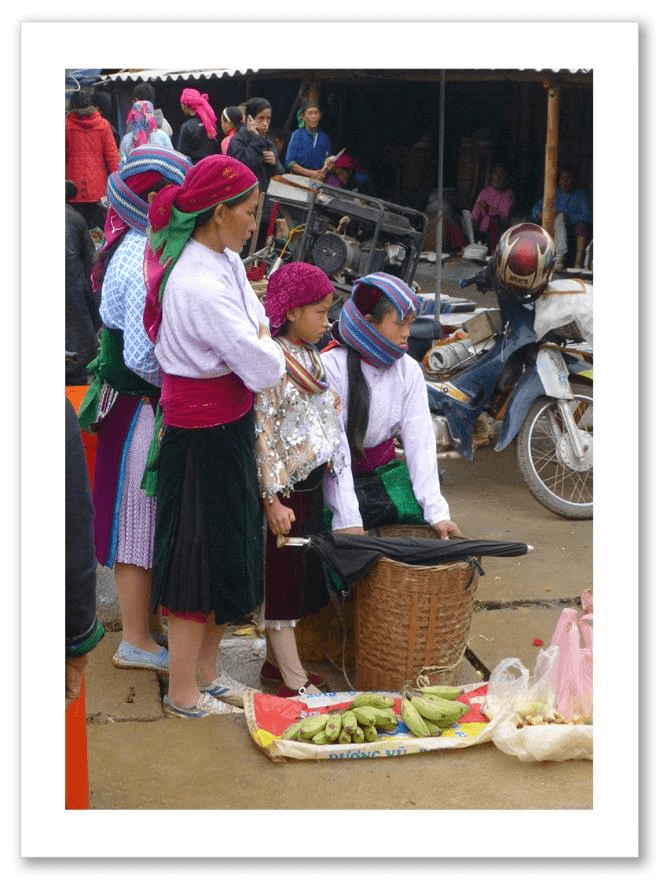

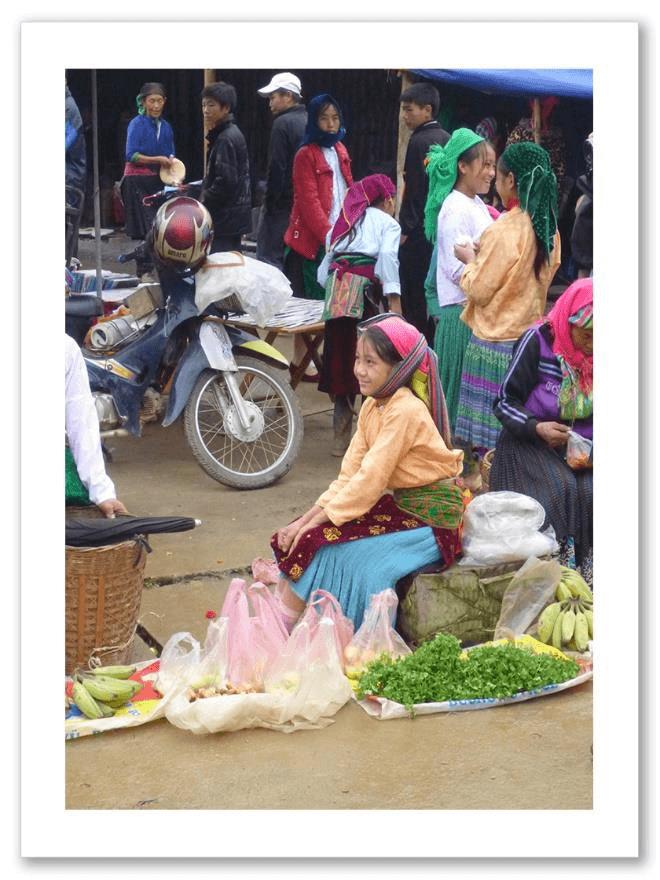

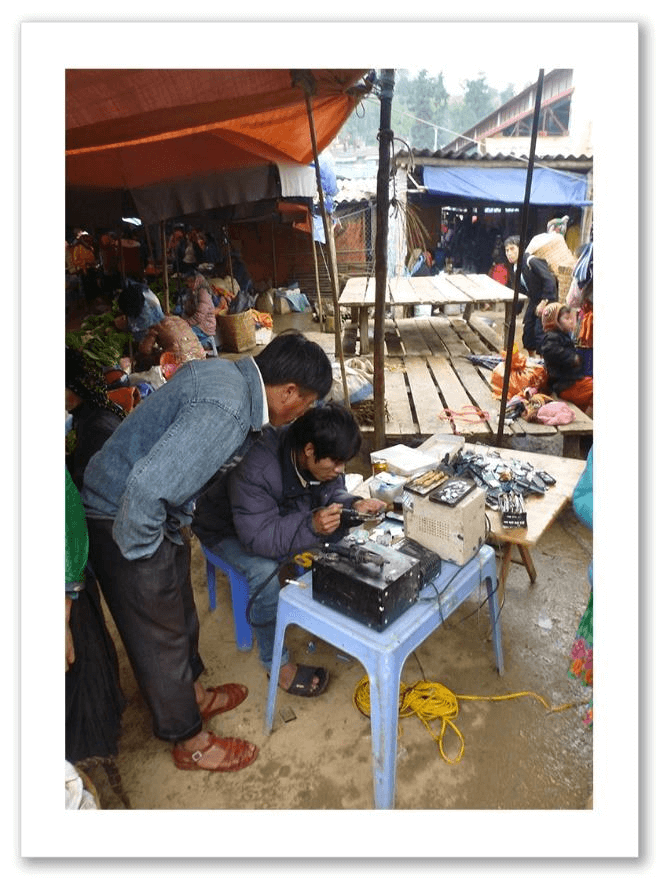

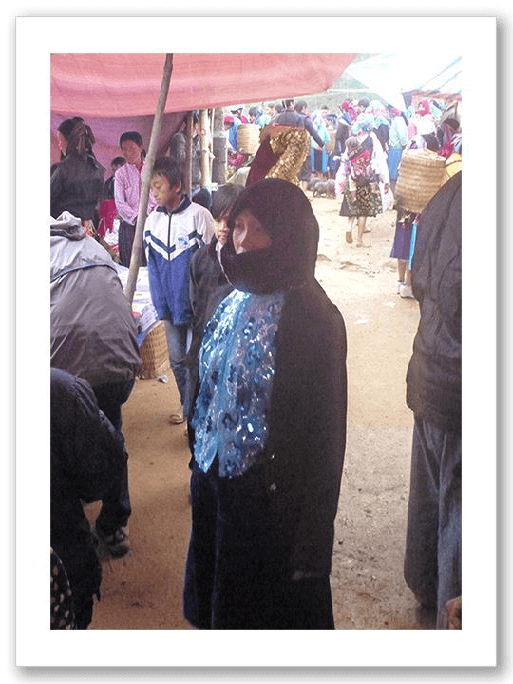

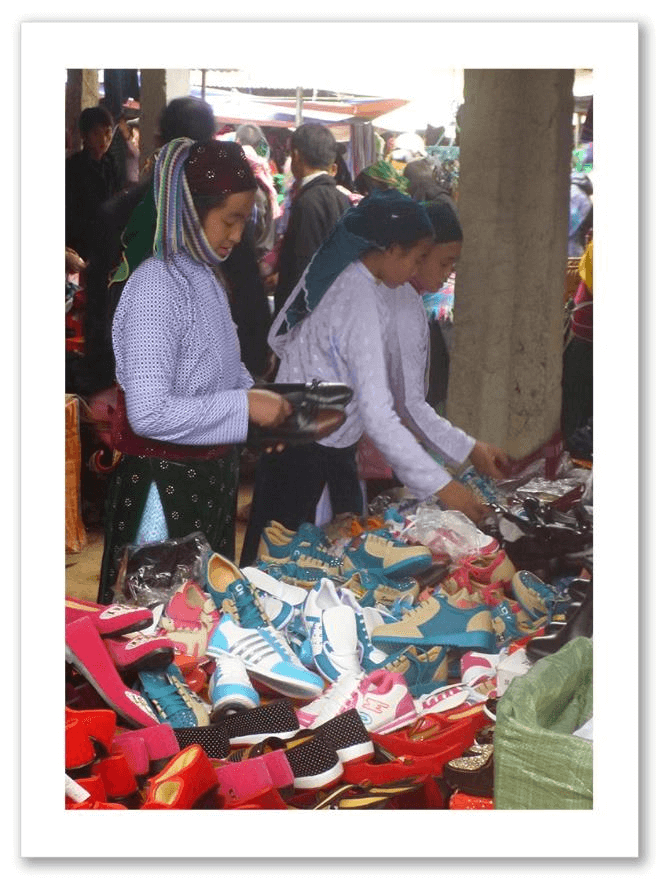

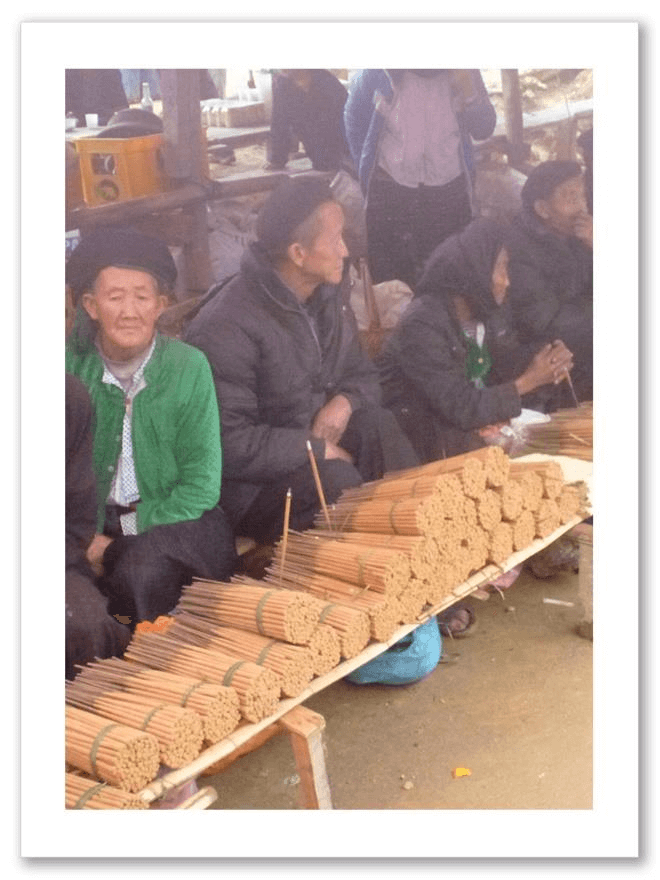

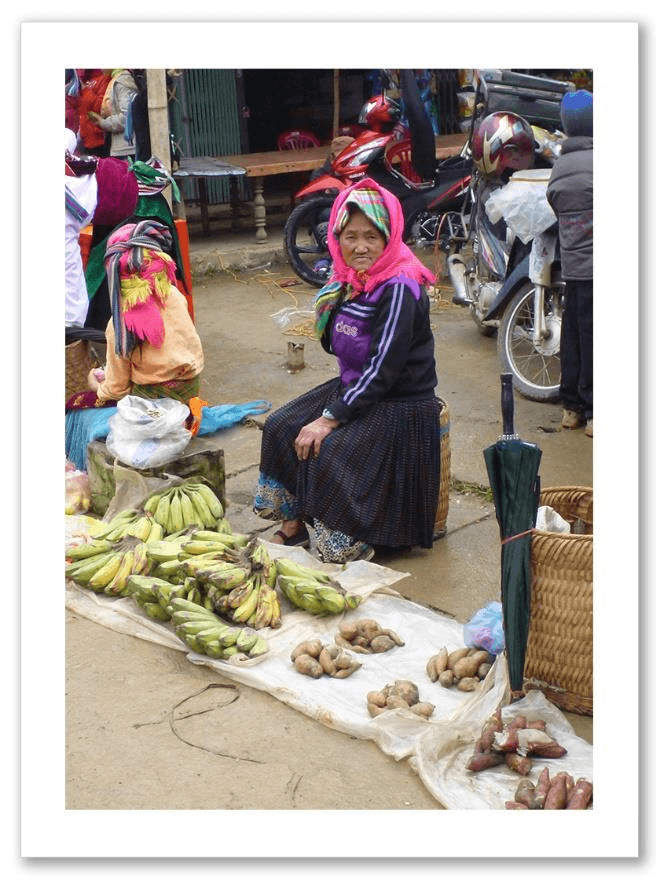

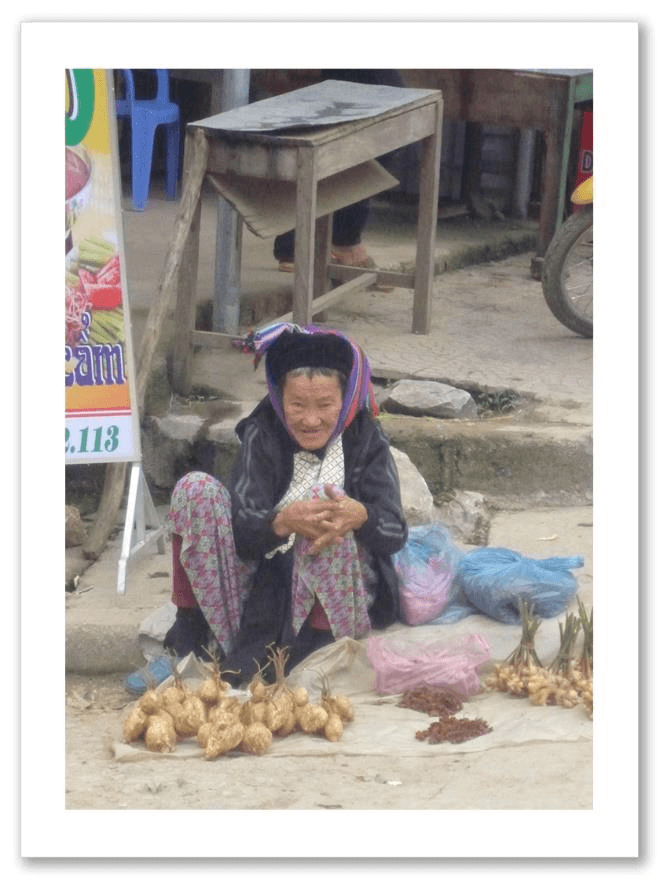

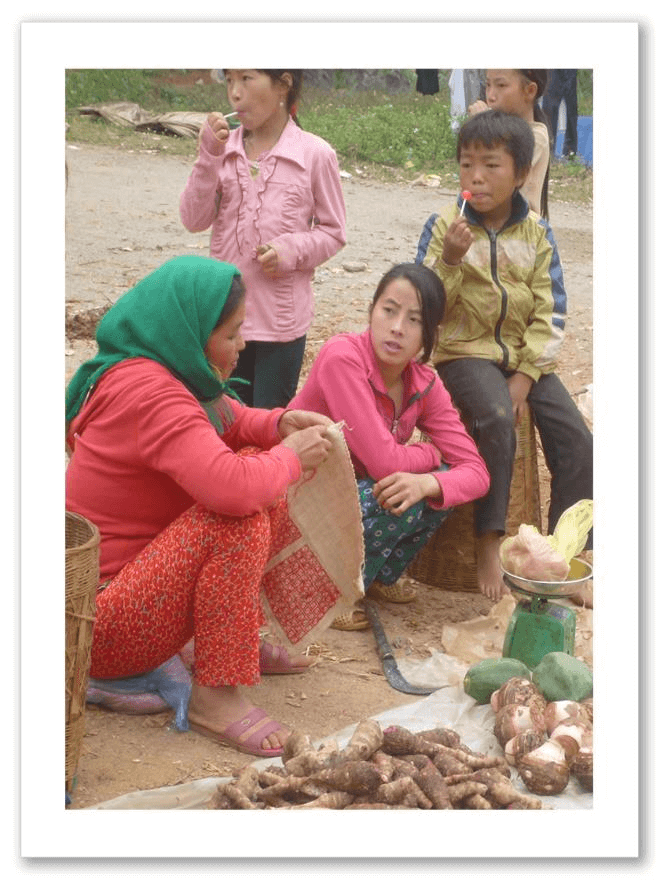

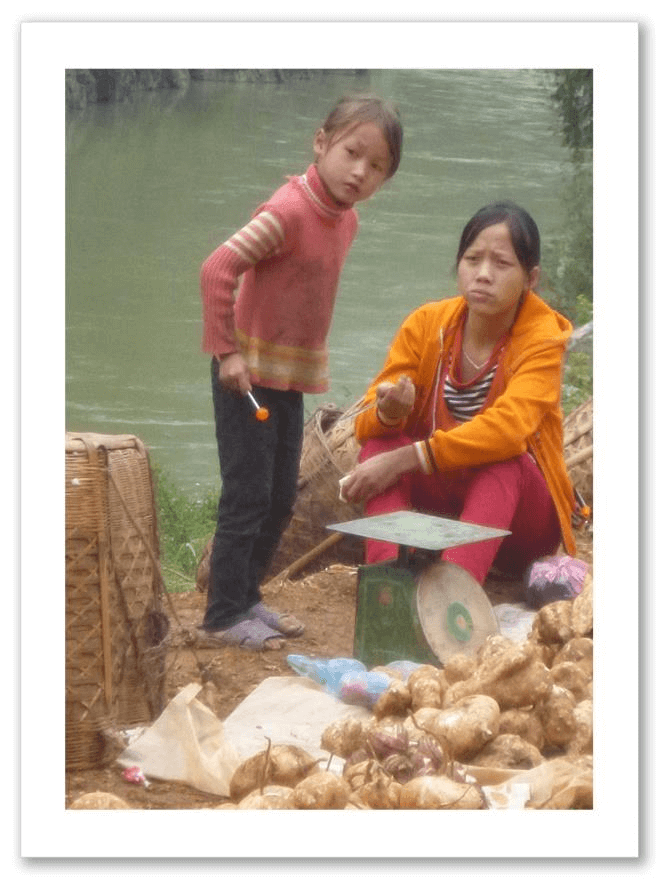

Ha Giang Market Day

-

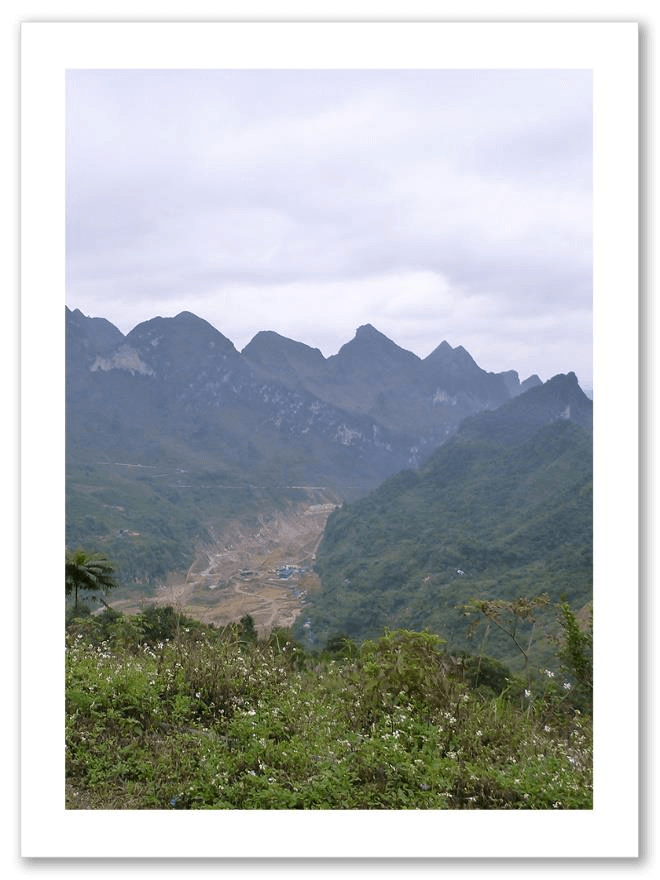

Spectacular Views Through Meo Vac • Nho Que River Gorge

Mapi Leng Pass -

Ha Giang to Cao Bang • “Beautiful But Not Spiritual”

Roadside Markets • Candy from Comrade Stone

An Eventful Massage -

Ban Go Waterfall • Tour Boat Competition • Tan Thon Crossing

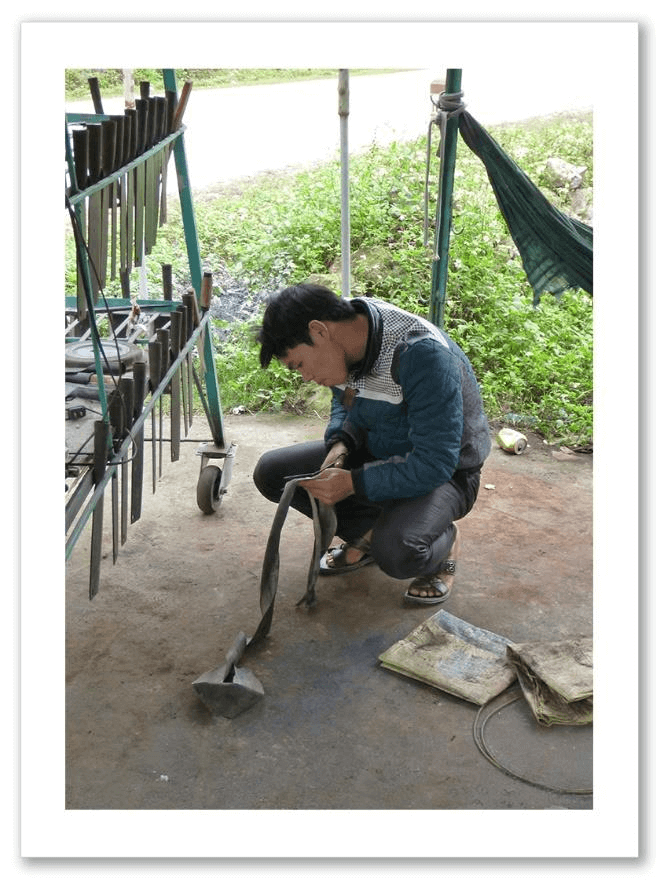

Cao Bang • Vietnamese TV • Long Sen Knife Maker -

A Viet Christian Lady Tells Her Story

-

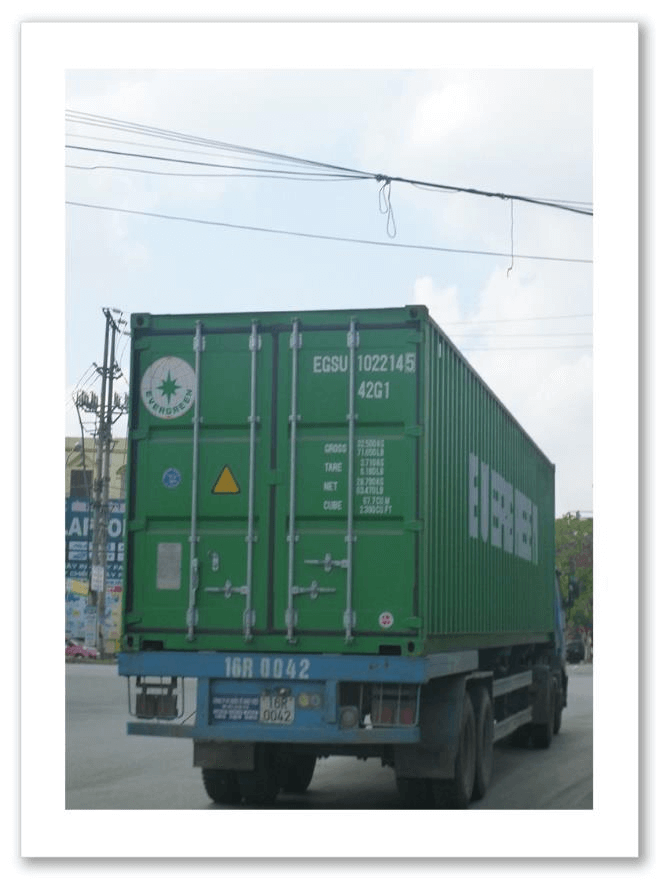

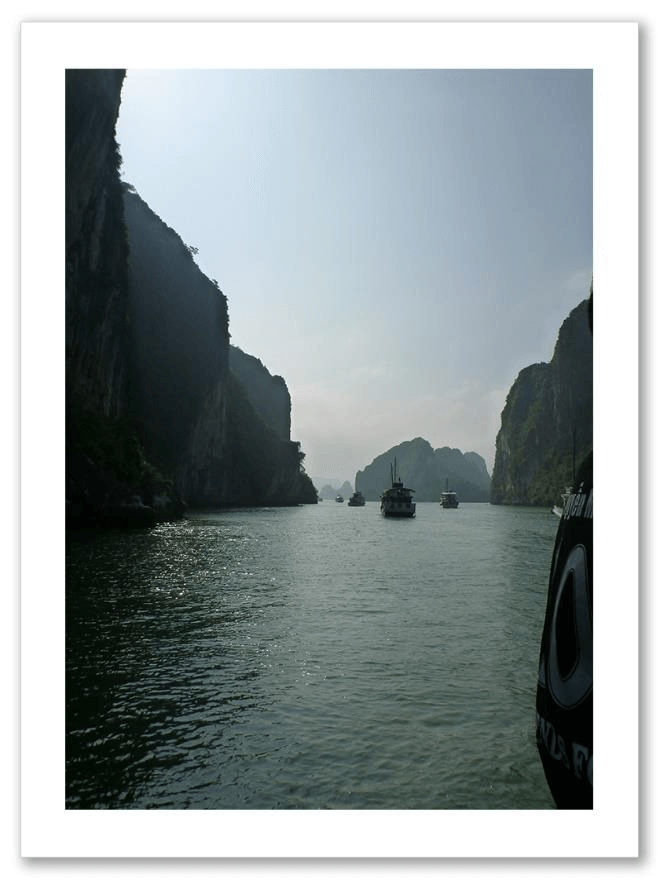

Long San to Ha Long Bay • Evergreen Truck Spotting

Booking the Boat Tour

– ii –

-

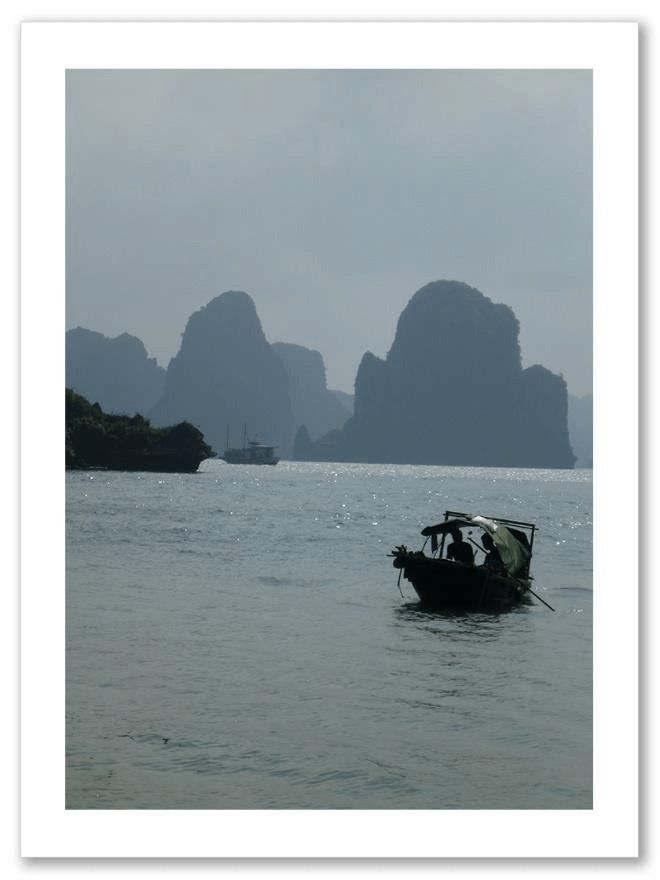

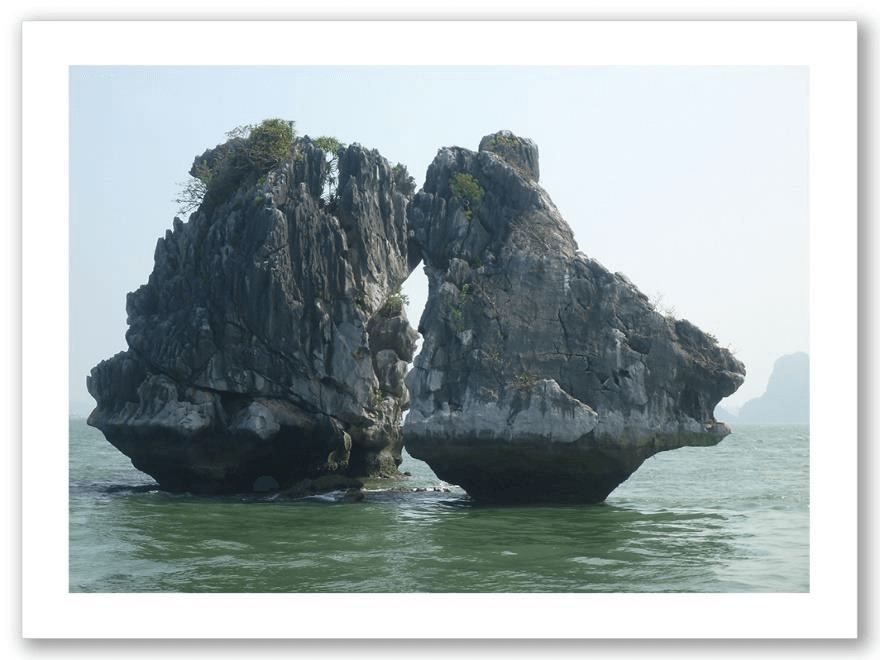

Ha Long Bay Boat Tour

-

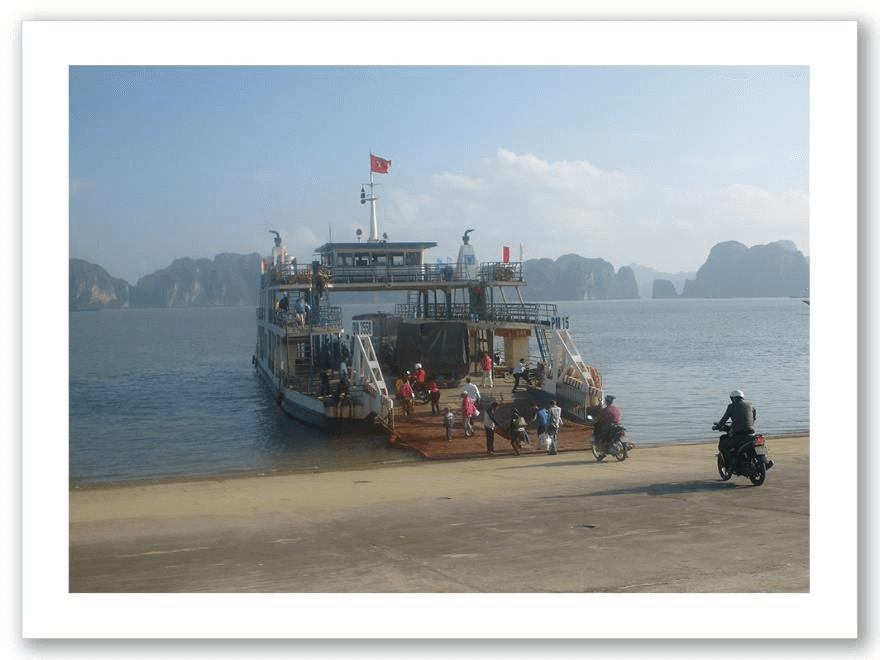

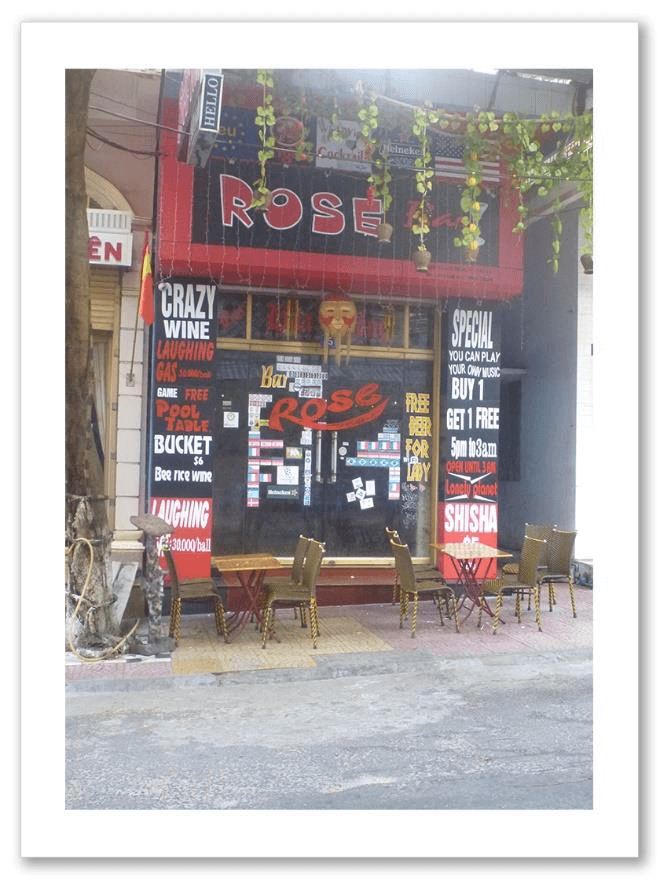

Ferry to Cat Ba Island • The Rose Bar

-

Ferry to Hai Phong • Wrangling in the South China Sea

Hai Phong Harbor Activity • Visions of Old Vietnam -

No Ho • No Ao Dai

-

Museum of Military History • Hoa Lo Prison (Hanoi Hilton)

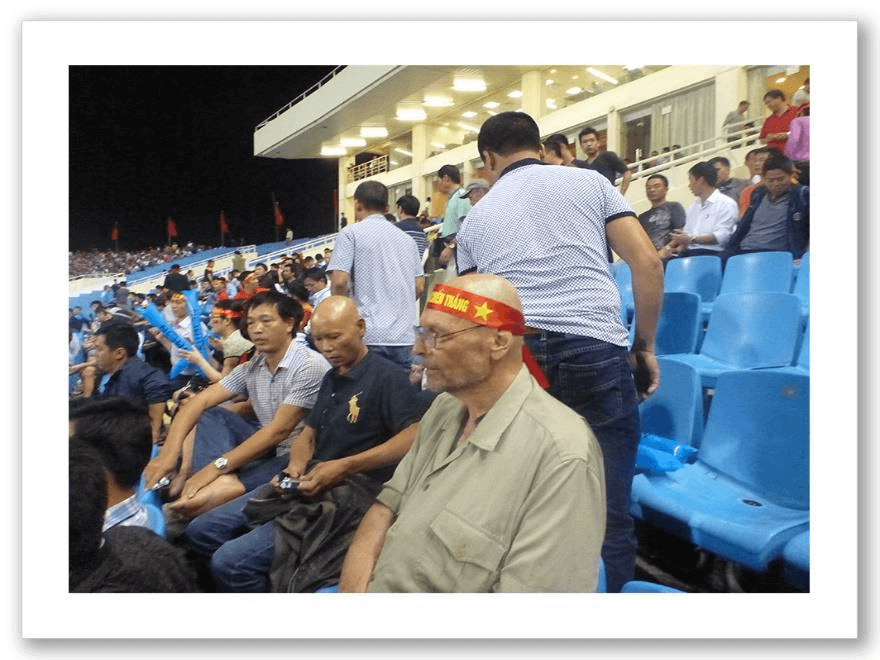

Indonesia/Philippines Soccer Match • Vietnamese Cheerleaders -

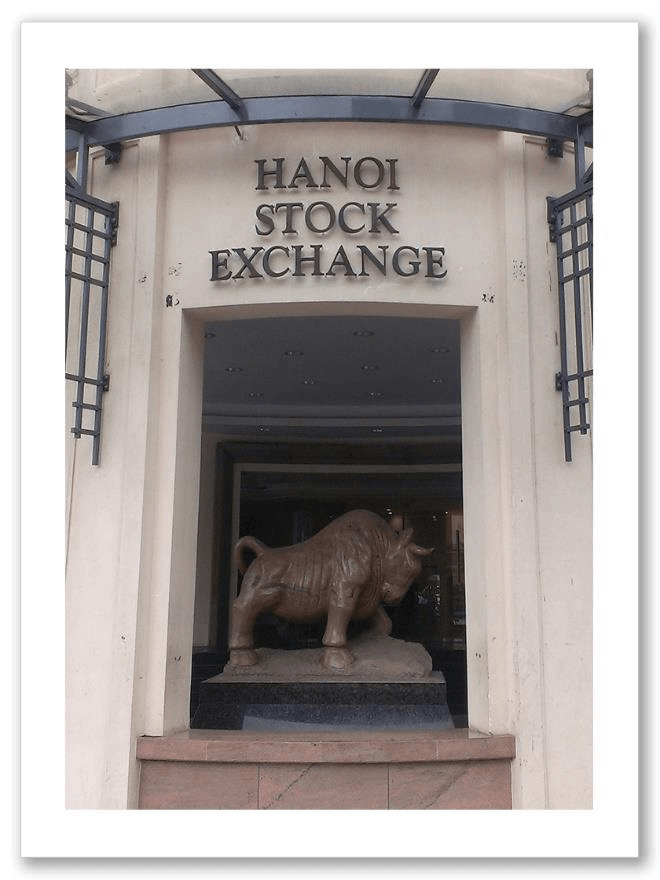

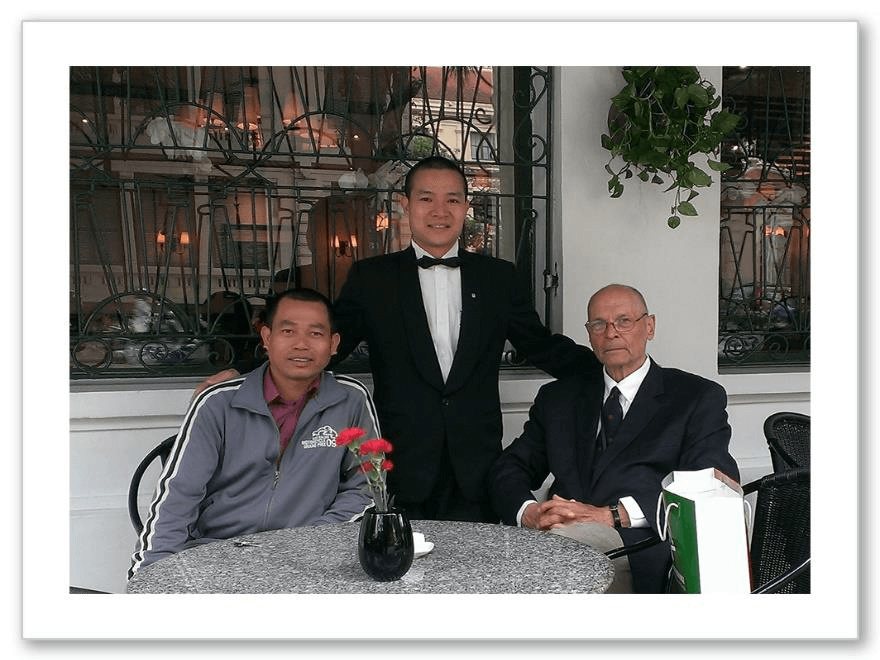

Hanoi Stock Exchange • Back to the Metropole Veranda

Ta Quang Bao Photos • Farewell to Comrade Stone -

Solo at the Metropole • Final Bride Judging

Back to Ta Quang Bao Photos • Farewell to Chicken Pho -

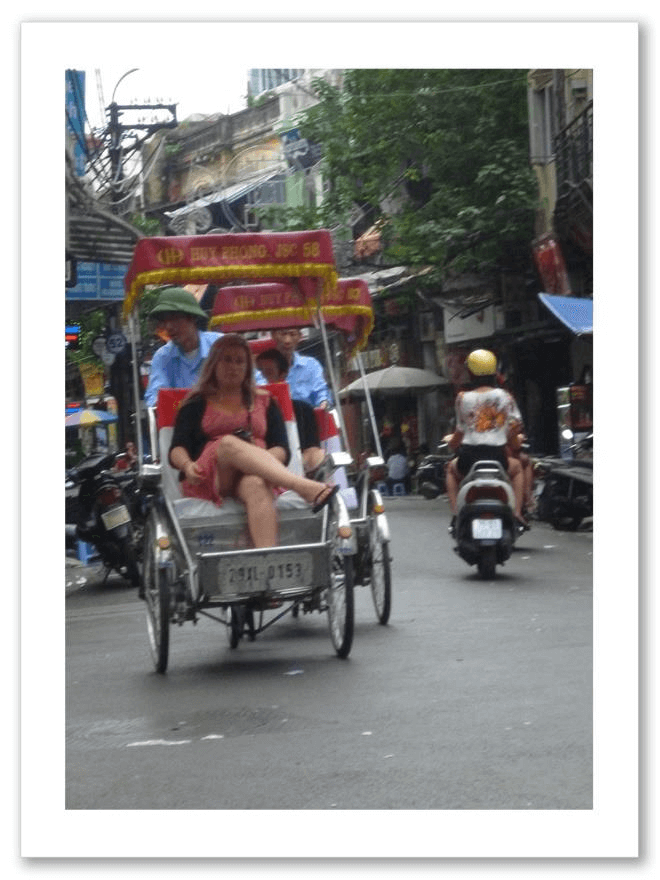

The Rickshaw and The Pedicab

-

Memories and Airport Musings • American Food Imperialism

– iii –

DELUSIONAL BEGINNINGS

Cancer is a terrible disease. It is painful, physically disfiguring, gnaws

constantly at your psyche and raises hell with travel plans, even plans that

were delusional and impossible to fulfill before the cancer took hold. None of

this was on my mind as I stepped off a treadmill in the spring of 2013, reason-

ably satisfied with my performance as I made preparations to walk a loop in

northwest Vietnam along the China border. As events would subsequently

show, this trip was poorly planned, wildly overly ambitious physically, and, if I

had been able to complete it, would have taken three to four months rather than

the five weeks I had allotted. A classic pipe dream with Vietnamese ribbons.

A short time after stepping off the treadmill I began to sleep for long

stretches, waking unrefreshed. Upon waking the room would spin and I would

find it difficult to make it to the bathroom without grabbing at the walls for

stability. In my mind those walls were closing in.

I constantly wanted to sleep in the most inappropriate places, including

jails, and at times during Red Sox games. Navigating subways became a chore,

with women as well as men offering me their seats. My walking became un-

steady and my feet made the slapping sound of patients with tertiary syphilis.

Once again women as well as men held the door for me at the entrance to my

apartment building. Finding myself suddenly old and sick was inconvenient

and a bitch.

One morning I awoke on a bathroom floor covered with broken glass. My

shoulder was badly cut and I had no recollection of how it happened. I checked

myself into the emergency room of a prominent New York hospital where I re-

mained on a gurney in a hallway for six days wearing the same clothes I had on

the day I checked in. I later found out I had been somehow lost in the system and

my so-called “treating physician”, a graying middle-aged hysteric, was heading

out to San Francisco for a six month rotation.

I put myself through law school working as a hospital orderly so it did

not cheer me to hear one of the orderlies say he was waiting around to see

when “Batchelder exploded.” The treating physician informed me that I had at

least three lymphomas, and one was near the pancreas; I knew if it was on the

pancreas it was tap city. He told me that I was being discharged—to what?—and

The Last Flight West

Page 1

that I should call an oncologist to make an appointment, in my mind just to see

how long I had to live.

Cancer engenders more fear than nuclear warfare, especially in someone

who at the age of twelve watched his mother die under horrifying circumstances.

Fortunately, two friends took over pretty much every aspect of my care. I will

not go into the details of the “treatment” except to say that at the initial meeting

with the doctor he advised me that if I did nothing I had at best four months to

live, and it was anyone’s guess as to how long I had if I took the “treatment” that

was proposed. Carol, a cancer survivor, urged me to give it a shot, and, like a

guardian angel, went with me every step of the way, including providing the

entertainment to get me through the treatment sessions. As the weeks crawled

along I became intimate with Poirot, Inspector Morse, Foyle’s War, and Inspector

Lewis and Sergeant Hathaway, absorbing the violence of each episode along with

the poisons being dripped into my body.

In the late 1950s when I was on my way to Australia for training, one of

my minders introduced me to the “House of the Dead” in Singapore. The practice,

which I thought barbaric at the time, was for families to bring their loved ones to

a house where others were dying so that they might live out their last days never

being alone. On mature thought I now believe they may have been ahead of their

time: families of the dying were always around, and no one was isolated or left

alone to experience death.

The words “infusion center” sound innocuous enough, but in fact describe

the room where patients are scheduled to receive their poison. I had the infusion

center experience six times and each time it became more gut wrenching. The

scheduling staff are all smiles, sweetness and light, but within that room raw

fear, screaming pain, despair, terror, love, compassion and spartan courage

clash like an emotional pinball machine: lights flashing, bells clanging, flippers

jerking, numbers frantically climbing in a universe out of control. If you are ever

depressed, feel like the world has not treated you fairly, and life seems not worth

living, go to an infusion center and just sit for fifteen minutes; it will save you

thousands in therapy.

After two treatments of the scheduled six I was told that most of the lym-

phomas were destroyed, but one was still slowly growing. I decided to carry on

through the next four treatments. Same prognosis as after the second treatment;

come back in four months and we will see how you are doing. Hey, good news, but

why did I feel like I was out of breath just going up the subway stairs?

Page 2

The Last Flight West

Unfortunately, heart problems are one of the “side effects” of the poisoning

treatment and although I was riding the six-months-almost-cancer-free train, the

AFib/congestive heart failure train had entered the station. Again, my guardian

angel appeared: Carol’s significant other had gone through two serious heart

attacks and she knew all about AFib and congestive heart failure. Good news—

I would not die doped up or screaming in bed with cancer as had my mother. I

could now stroke out or end up a drooling paralytic—not a cheery future. Bottom

line, I now take so many heart pills that I oft times confuse one with another, also

not a good thing.

Despite all of the medical developments my dream of L’Affaire Tonkinese

Alps did not die, although it had dimmed considerably and was flickering ever so

slightly when I raised it with my doctors. One initially asked, why not Italy?

Still, to my surprise they gave grudging assent. Admittedly, I wasn’t completely

candid about what the trip would entail because I myself didn’t know, but one

thing for sure: if I could get on an airplane I was going.

Travel Plans: “The Last Flight West”

The genesis for this trip sprang from discussions with Comrade Chris on

the “Street Without Joy” outing. She shared some of my disillusion with Saigon

and suspected that I might find Hanoi more to my liking. My ideological stop-

watch immediately shot her suggestion down, but as time passed I went back to

“Lonely Planet” and the section on “Roads Less Traveled” in the northwest region

of Vietnam. The voices of the Tonkinese Alps and the tribal regions beyond Ha

Giang and along the Chinese border called, and now with a renewed sense of

urgency.

My plan, and it was beyond stupid (delusional would be a better word) was

to make the loop from Hanoi to Dien Bien Phu up to Sapa, then to Dong Van, then

to Meo Vac and back to Hanoi. I thought if I carried my own sleeping gear I would

not encounter the “people to people” problem I had on my earlier adventure.

Sure, I would be carrying close to sixty-five pounds, not speaking a word of the

language, and would, in my mind, be able to do twenty kilometers a day. Clearly

“The Others” were piping nitrous oxide into my apartment; and did I mention, I

gave myself only five weeks to complete the loop? Knowing what I know now, I

would have been lucky to have reached Sapa alive within a month, and I would

The Last Flight West

Page 3

have had to be in Ranger shape to do it—just slightly north of mad to have even

considered it. Cancer and congestive heart failure changed all that.

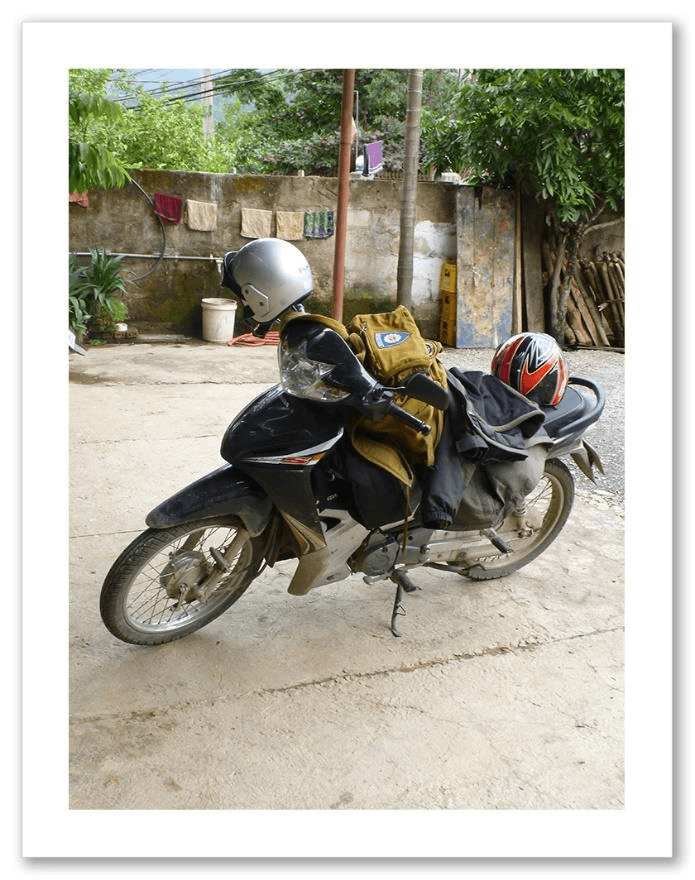

Next, I, not having ridden a motorcycle for sixty years, became enamored

of the idea of a motorcycle escapade employing an old Belarus Minsk motorbike.

The travel gurus at Lonely Planet loved the idea, but more later on about how this

particular notion crashed and burned. However, the lunacy was still alive and

well as I started to prepare for the trip. In fact it was Plan A. Put simply, I was

to learn to ride an unreliable Soviet—this for starters—motorbike and set off into

some of the most dangerous terrain in all Indochina, not speaking a word of the

language. That day the nitrous flowed freely. Tish, tosh! What stumps me is

why my friends did not have me committed. True, I had not spoken with them

in depth about my plans, but if I was blind to the insanity they clearly, smart as

they are, were not. Nevertheless, there must be something to the power of per-

suasion of the last wish on the bucket list that overcomes common sense, casting

a glow of the possible around the dark moon of the impossible.

In my delusional mind all I had to do was to learn to ride an essentially

unreliable thirty- or forty-year-old motorcycle, take off for the Tonkinese Alps on

treacherous roads and, sick as I was, live happily ever after for about five weeks

before returning to civilization, and, dare I add again, not speaking a word of the

language. These thoughts were not front and center as I boarded the plane. Pas

de problème, I would have four days after I arrived to sort it all out.

Page 4

The Last Flight West

THE LAST FLIGHT WEST

Day One

Twenty-six hours airborne

I boarded my Air Vietnam flight (best to fly in with the enemy) and for

twenty-six hours flying time I watched the image of the little plane move across

the screen. Frankly, I never thought I would make it, never mind to a country

whose political ideology was such an anathema to me. As we approached Hanoi

late at night I tried to imagine what it must have been like flying into the most

heavily defended city in modern air warfare with SA-2s, ZSU 4s and just granny

on her back shooting at nothing, all blazing away. I lost two pilot acquaintances

to the Hanoi defense system and I was not in a loving mood. On the descent and

approach I noticed vast swathes of darkness, and as I glimpsed Hanoi itself it did

not appear to be a large metropolis. I had failed to figure in the late (midnight)

time of arrival.

The plane door opened and for some reason a couple from Minnesota

latched on to me, asking me to help them navigate Customs and Immigration.

They were coming to visit their daughter who was working in Hanoi. By the tone

of their words I believed they considered this development somewhat akin to a

death sentence. I assured them, without a shred of evidence, that Hanoi was

very modern and they would love it. Fate intervened as there was a problem

with my passport and the couple disappeared into the wilds of Hanoi never to

be seen or heard from again.

Thanks to my friends, and for only the second time in my life, I was met by

a car. I quickly realized I had packed for cold temperatures and instead it was

hot and humid. As we left the airport I noted a massive construction project, a

joint venture between the Taesi Company of Japan and the Vietnam government.

I bought Taesi stock in 1968 on the recommendation that they would be able to

get just such contracts and I was pleased that my dividend of $34.00, which has

not gone up in thirty years, was presumably safe.

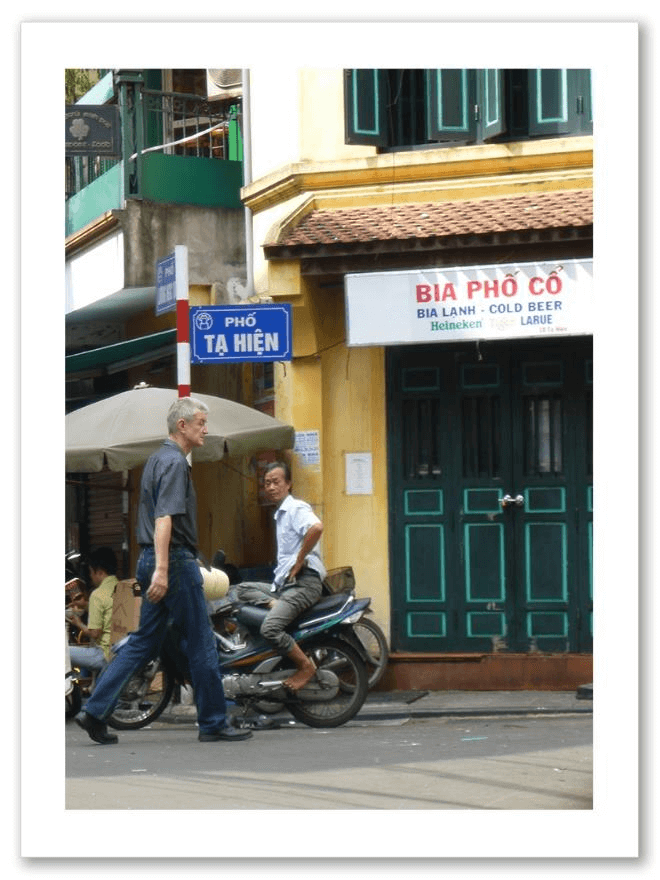

I then went into Hanoi’s “Old Quarter” and even at that late hour the am-

bience of old Saigon bloomed, and it embraced me. The street level entryway to

my hotel was flanked by four parked motorbikes; the lobby was a flight up with

no porter to carry the bags. It was 1:30 in the morning, but it had nonetheless

not escaped my notice on the way in from the airport that a spanking new Honda

The Last Flight West

Page 5

dealership, almost a block long, had just opened; with lights blazing full on I

could hardly see the cars for the wattage. As I staggered to the hotel’s front

desk, fate fortuitously rolled the dice again. I was greeted by a Scotsman with a

brogue so thick you could cut it with a knife. This chance meeting was to have

incalculable consequences for my trip and for me personally.

The ex-pat stated he was just covering the front desk for a moment; two

other hotel employees were asleep on couches. We started chatting about Scot-

land and I asked him how he had voted on the referendum. He said “Yes” which

allowed me to put my political feet on firm ground. By chance, he saw my folder

which bore the caption “The Last Patrol” and he, not in a prying manner, said

“there must be a story there.” I told him what I was trying to accomplish and he

indicated he had just spent two days with a motorcyclist and maybe he could

help. He told me to wait while he searched for the guy’s flyer. After fifteen min-

utes he returned and said he had thrown the flyer in the wastebasket and that’s

why it took so long. Lucky for me the housekeeper had not taken out the trash.

I looked at the flyer and took it with me to the room. Because of this chance

encounter Comrade Stone was soon to enter my life, and what a fun ride it was

to be.

As I lay down to sleep I noticed the following statement laminated to the

nightstand. I quote verbatim:

“We understand your room is facing the street, it

has alots of noisy from the street which commons

happen in Hanoi.

“We are served ear plugs at reception, pls call us

and return them at reception when you check

out.”

Although weak, dead tired and above the seventeenth parallel, I knew I

was going to like this hotel, and, despite my deep political reservations, probably

this town.

Page 6

The Last Flight West

Day Two

Hot, humid

Revolutionary fervor on high flame

Promptly at 06:00 a harsh high-pitched female voice began to bellow out

the news to one and all. It has always seemed to me that Hanoi deliberately

breeds these harpies with their shrill penetrating voices, a technique straight

out of Camp 13. Me, I could care less as breakfast was free, and as my last wife

taught me, among other things, nothing is more important than free food. Up

to the fifth floor to a charmless little restaurant serving six tables, with the

loudspeaker located not far down the block.

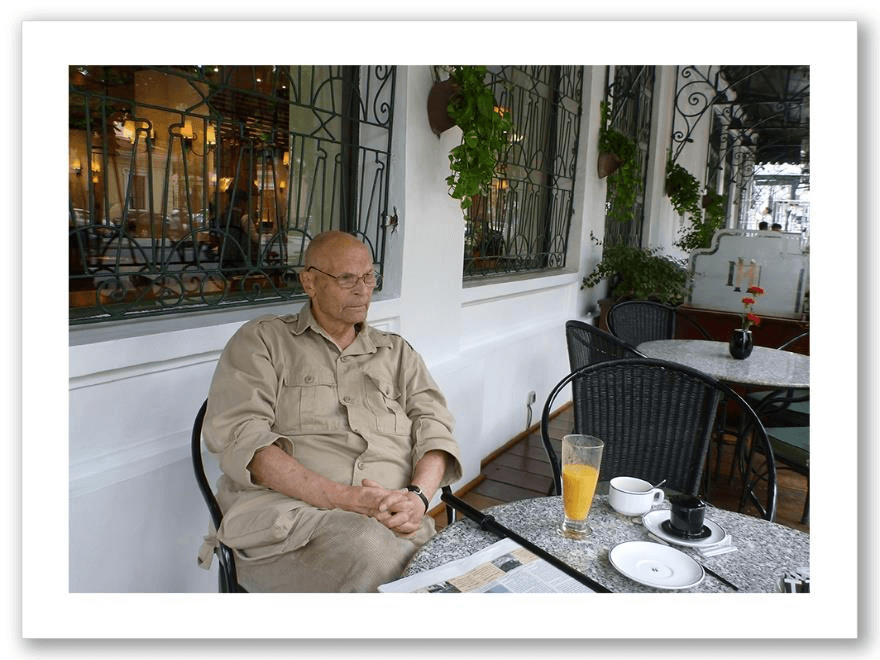

A couple was there before me: he racing towards fifty, and he had such a

good time last night he didn’t shave; she,

quite a bit younger, wearing a dress that

begged to be consigned to the flames. She

was, as my mother would say, “fast.” He

wants more; she has had enough. Each

retreats to a cell phone to communicate

their displeasure, to whom I could only

imagine.

Both are chatting away too long and

too loud until she spies a lady of the night

enter with a rather attractive thirtyish

Caucasian male. She lays down a stare of

napalm two feet wide on the floor of the

restaurant. At first hubby doesn’t notice

the lady of the night but when he does,

cell phone chatter stops. Game on. Up-

on being seated, lady of the night does

not fire back a stare but takes a lovely

manicured foot from her sandal, toenails painted fire engine red, and angles it

toward husband for him to admire. Matron is onto, not her cell phone now, but

iPad, and husband is in another world, or soon will be, as they leave. Me, I am

clearly watching conceptual art—note the TV antenna which dominates one of

the dining room views—living, breathing art. Not a bad start to the day as the

revolutionary loudspeaker broadcast wraps up with some very European

sounding marches.

The Last Flight West

Page 7

I cannot find an English language newspaper, so I decide to pick up some

revolutionary propaganda posters and am told the shop I want is just a five min-

ute walk away. I promptly get lost in the “Quarter” and as I wander around I

cannot understand why shops selling the same goods are all cheek by jowl on

the same street. I subsequently learn that this arrangement has historical ante-

cedents, but how do you make your selection? I am clearly going nowhere fast,

so I ask directions from a clothing store owner who turns the store over to his

associate and tells me to jump behind him on his bike. After a ten minute hair

raising ride in Hanoi “Quarter” traffic he deposits me in front of a shop. When I

offer him payment he refuses, and roars off, yet another of many courtesies I

continuously receive in Vietnam, both north and south.

As I alighted I noticed another propaganda poster shop right across the

street. Capitalist warfare between propaganda shops (!) although I doubt that

they enjoy a booming business. I meet a charming salesgirl, I would say about

twenty, dressed in red. Given her age we will have none of the reminiscences

generated during my visit to Lotus in Saigon.

From gentle questioning, and based upon my review of the posters, it was

clear she was clueless about the revolution. I selected several posters, some

classics, for my left-leaning friends back home, and I then had the temerity to

ask about the shop across the street.

With a slight arching of her eyebrow that would liquidate any “leftist

deviationist”, “rightest deviationist” or “roader”—in fact, anyone suspected of

the slightest revolutionary impurity—she opined that the rival shop was not

“authentic.” I found this interesting as her competitor prominently displayed

several of the same posters I had just bought, two of which are classics. Having

been suitably chastised I knew it would be foolhardy to cross the road to explore

the other shop. Even in a revolutionary context capitalist competition does

strange things to people.

As it was nearing mid-morning the sidewalk cafés were doing a brisk

business, with cycles parked end to end and everyone engaged in earnest dis-

cussion of the human condition. Hey, I was in Hanoi. I was hoping for a little

more proletarian ambiance and did I ever get it.

I wandered around and found a conjunction of three roads opposite a dis-

tributor for Heineken, no less. The New Hampshire beer crowd would dismiss

my selection, Becks drinkers to a man. The distributor was far from the madding

crowd and had a store, if you can call it that, about four feet wide and ten feet

Page 8

The Last Flight West

deep, with four shaky stools of Chinese manufacture meant to support Lillipu-

tians. Granny was asleep without a mat on the floor, and I asked for a Teddy,

which is a fake orange Minute Maid drink, almost pure sugar, but in my condi-

tion did I care? I sat down to watch the action.

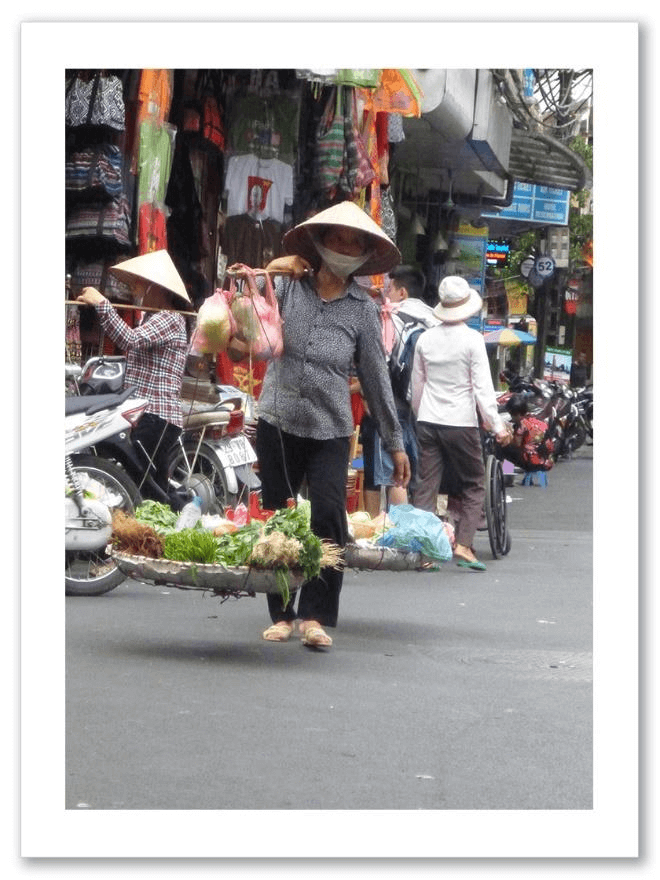

To speed up my welcome I bought eleven yellow roses for granny from a

flower pole seller. (N.B. All Hanoi pole sellers are women.) Things started to

heat up as, unbeknownst to me, one of the streets running off the square is an

oft photographed locale, where soon to be

married couples pose to have their pictures

taken. This ghastly Old Hanoi street with

all the charm of Bridgeport or

Bayonne: why there? I never

got an answer. A somewhat lost

soul indicated he was waiting

for the Heineken bar to open up

and would I stand him a lunch.

I did so.

“Le Mouvement” in the

Quarter was very interesting.

The pole sellers who serviced

the more upscale section of the

Quarter passed by on their way

The Last Flight West

Page 9

to the more affluent streets two blocks away. Granny’s neighborhood was very

tight knit, and when word came down that the police were cracking down on

customers drinking beer

from the tiny shops my chair

was seized from under me.

I stayed by the shop pretty

much the whole day and gran-

ny only sold three beers.

You know you have

arrived when after two hours

the street vendors who offer

to glue your shoes and the

fake Zippo lighter guys pass

you by with a knowing smile.

Jet lag was catching up to me

as were the heat and the humidity, so I headed back to the hotel, got lost again,

eventually found the hotel, and turned in early, secure in the knowledge that

propaganda harangues and revolutionary music would start my day tomorrow.

Page 10

The Last Flight West

Before I turned in I made a call to Comrade Stone who said he was available to

ride tomorrow. One of the best calls I ever made.

Day Three

Hot, humid

No revolutionary fervor

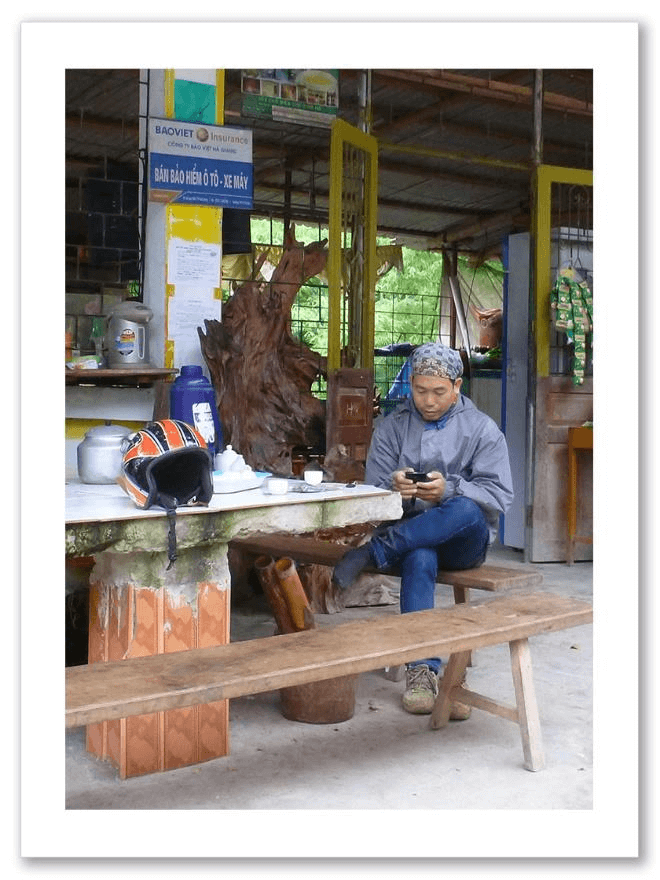

When I arrived in the lobby I was greeted by a middle-aged man, physically

looking tough as nails. He was wearing jeans, and otherwise nondescript clothes,

but sporting a rakish pirate bandana. He told me his name was so difficult to

pronounce his teacher had named him

Stone, and I pronounced him Comrade

Stone. This exchange launched what I hope

will be a lasting friendship. After initial

introductions he asked where I wanted to

go. I had a list prepared and I told him the

Tao of the List would get us through. Over

the next four weeks the Tao of the List

would be our touchstone. We mounted his

bike which I christened, despite its being

black, “Red Rage” and we dove into Hanoi

traffic, headed for Ho’s mausoleum; as it

was Sunday, we were far from

alone. Indeed, I was scared half to

death just getting there, as Hanoi

traffic is chaotic and breathtak-

ingly dangerous. I had never

ridden tandem on a motorcycle

before. Comrade Stone told me to

“just hold on.” I did just that, but

changed my pants four times as we careened through the traffic.

The Last Flight West

Page 11

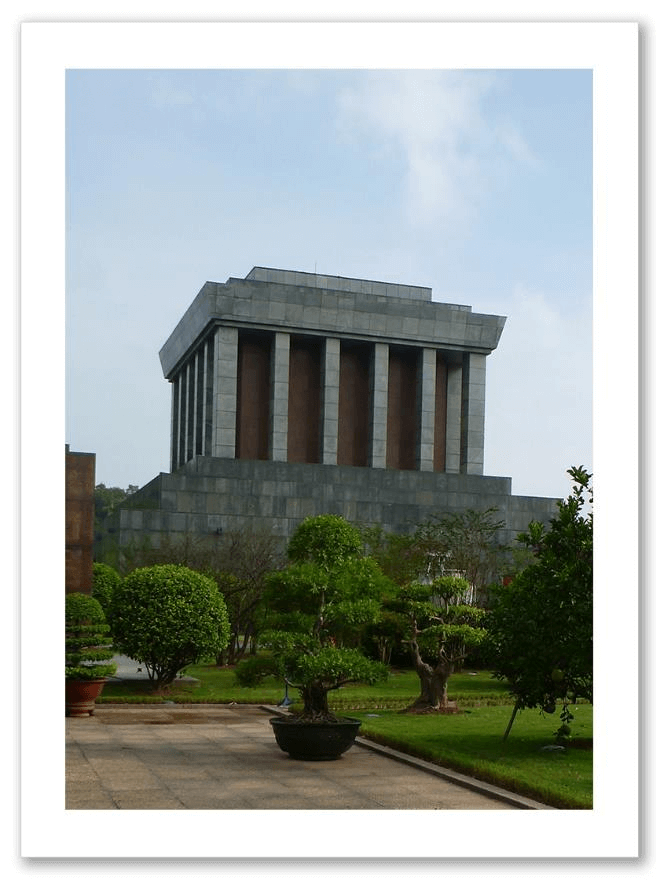

The mausoleum is a soulless

Soviet style monstrosity and was in

fact not open to the public as Ho’s body

was, at that time, being chemically fine

tuned by Vietnamese specialists. This

was a matter of great pride to the Viet-

namese because in the past the body

had always been taken to Russia. The

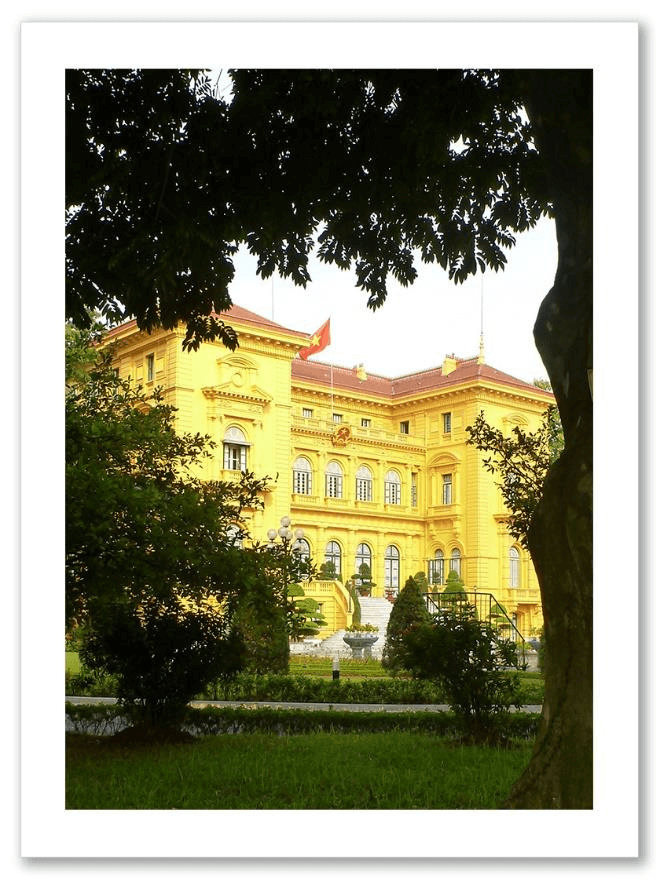

grounds were pleasant enough with

the magnificent French architecture

of the former Governor General’s

home, but the real story is to be found

in the three Spartan scholar-like rooms

from which Ho conducted the war

against America.

I stayed for quite some time

contemplating the American way of

waging war as revealed by former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates compared

to the Vietnamese way of waging war.

Three rooms with six pieces of furniture—

hardly fit for a staff sergeant—yet they

won the war. There is a lesson here, Bob!

The three rooms would barely fit in a

Pentagon broom closet, and pose a stark

contrast to the opulence of the Washington

and Northern Virginia war establishment.

The aesthete with the small borrowed

sword routed and ignominiously defeated

a decadent heavy metal American military

machine. Forget the mausoleum. The

story is in those three Spartan rooms.

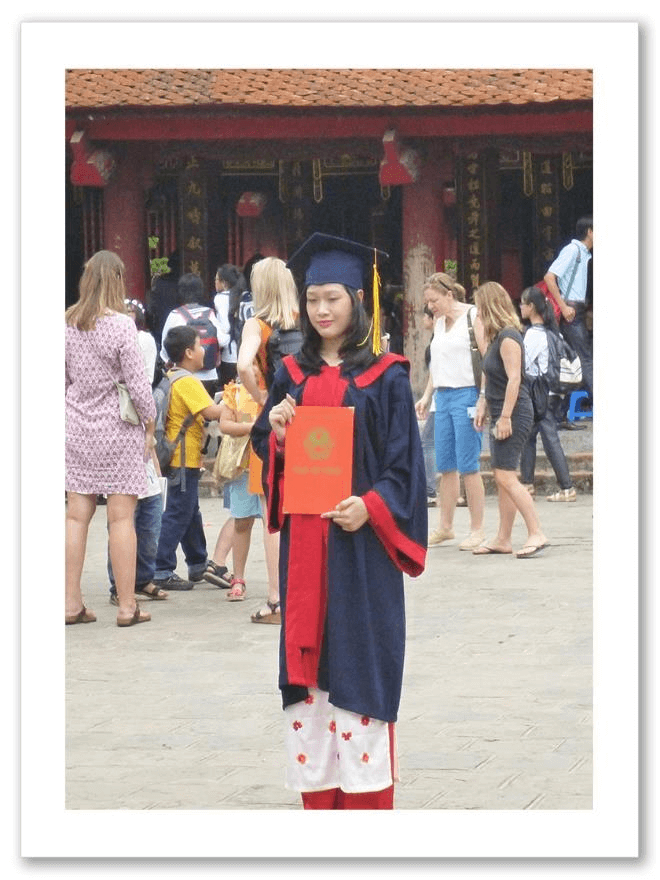

We then went from war to the heart

of Confucian education—the Temple of

Literature. Impressive grounds and much

kerfuffle as it was graduation day for one

of Hanoi’s best universities. I was puzzled by the fact that female graduates

Page 12

The Last Flight West

outnumbered males ten to one. Comrade Stone had the key—girls work harder

than men, and the faculty graduating was accounting which attracts many

females. Somewhere I knew

Germaine Greer and Gloria

Steinem were beaming.

No gold chains, no boom

boxes on shoulders, no vulgar

shirts or petulant child non-

sense—simply proud parents

and serious students celebra-

ting a day that a few years

prior was unimaginable. All of

the young women wore ao dais

as they posed for traditional

style photographs.

I wistfully watched proud parents

and their reserved and gracious sons and

daughters. I thought of the challenges

their parents had faced from the Colossus

of the North, and how the revolution, no

matter how bitter its Marxist political pill,

had produced these dignified graduates.

Nowhere here an event sullied by self-

indulgent rabble with bared breasts and

caps on backwards, their rowdy cat-calls

drowning out the graduation speakers.

We could learn a few things from these

grateful, graceful young men and women.

A calligrapher was in attendance

and having no business he was engrossed

in reading a Vietnamese pulp magazine.

With Comrade Stone’s assistance we were

able to converse, and he told us that very few average Vietnamese come to the

Temple, more likely foreign tourists who were not interested in his art. The last

American customer requested he put Mickey Mouse into calligraphy. He con-

fided that he created something vulgar but that the tourist didn’t realize what he

The Last Flight West

Page 13

had done. I applauded his intellectual guerilla warfare. I then requested he

depart from traditional calligraphy and using a broad brush make a powerful

“tiger” with little or no refinement. This he agreed to do, and after three at-

tempts he was satisfied. It is a most powerful piece which would later become

my parting gift to Comrade Stone.

As we departed the Temple we en-

As we departed the Temple we en-

countered a young Vietnamese woman

in an ao dai examining the flowers—and I

am immediately transported back fifty

years to the white schoolgirl ao dai. Viet-

namese American author Viet Thanh

Nguyen in his recent book Sympathizers

asserts that western writers take the ao

dai as an implicit metaphor for Vietnam

as a whole: “wanton and yet withdrawn,

hinting at everything and giving away

nothing in a dazzling display of demure-

ness, a paradoxical incitement to temp-

tation, a breathtakingly lewd exhibition

of modesty.”

I am of a more simple bent. The ao

dai is simply the most elegant, sexy dress

ever made without displaying an inch of flesh except above the neck and below

the cuffs; the cheongsam and other folds of cloth come in at a far distant second

place.

Buoyed by this vision and the intellectual ether, we headed to a street

featuring military and war detritus to search for a Vietnamese Red Army belt

buckle requested by a Russian friend. This was a most interesting experience.

These shops are lined up one after another for two blocks. Despite the fact I was

in East German garb with a Spetznaz hat, two shopkeepers would not deal with

me, flatly waving me away. But one vendor was willing and I purchased a mod-

ern “Communist” buckle as none of the “real” army ones are left. I asked the

shopkeeper about business and he said it was lousy as the young men were only

interested in western clothing and hip-hop garbage. He said all the shops were

just hanging on.

Page 14

The Last Flight West

Next we went to Craft Link, a fair trade store that markets ethnic goods.

The approach is somewhat unusual in that you go upstairs, climb out a window,

walk along a verandah to another room, then up a flight of stairs to the third

floor. First store in the world I have been in where you had to be a bit of an

acrobat to get to the merchandise, but it was worth it. I was the only customer

and the saleswoman was attentive. She explained the tribal embroideries, and

the significance of the rectangle, and the various wall hangings which she

described as a passageway to the soul of the mountains. She asked about our

destination and was pleased when we told her the Ha Giang area and beyond.

She said not many Europeans go there and predicted that I would like it as

there were many friendly spirits. I bought one of the wall hangings for a friend,

although I wanted it for myself.

Over dinner I advised Comrade Stone of my plans and he was decidedly

subdued, advising me that the Minsk bike was a non-starter and gently suggest-

ing that, given my lack of skill, the whole solo bike thing was bordering on crazy.

He said it was mandatory that I train on the bike as the planned itinerary in-

volved some stretches that were dangerous as well as physically demanding.

He proposed we should run a test to see just what skills I had but we should only

use a bike manufactured by the wonderful people who bombed Pearl Harbor. He

informed me that the bike would probably speak excellent Mandarin as well as

Japanese; the Chinese were flooding the market with Honda parts. We prepared

a Tao list for the morrow, which involved drinks on the verandah of the Metro-

pole, the B52 museum, aircraft wreckage, the revolutionary museum; the Tao list

was growing! At seventy-eight I was preparing for mental and physical tests any

seven-year-old, or perhaps even younger, could pass. The pressure was on.

That evening I strolled Pho Hang Giay, the “night market”, from end to end.

One big tourist trap of western clothing, but the shoppers were overwhelmingly

Vietnamese. The whole event, although commercial, appeared to be essentially

social with side streets doing a booming sidewalk food business.

I am again shocked at how the Five Year Plan boys can let this continue.

I understand they want to move people out of the Quarter, but it is such a money-

maker the uproar would be heard in Lenin’s tomb—more of those devilish Marx-

ist contradictions.

The Last Flight West

Page 15

Day Four: Early

Hot, humid

No revolutionary fervor

Comrade Stone decided that before we went to the Metropole we should see

the B52 Museum, the B52 in the Lake, and the Air Military Museum. We started

with the preserved portion of a B52 undercarriage in a small pond in a quiet

Hanoi neighborhood. I spent

some time looking at the

engineering of the undercar-

riage and, although I am not

an engineer, it is clear the

B52 is a sophisticated piece

of equipment. The question

that formed in my mind was

how, in less than a generation,

could Vietnam go from a plow

economy to a sophisticated air

defense system capable of

defeating the most highly

developed electronic countermeasures.

developed electronic countermeasures.

The answer is an intense education based

upon strict meritocracy, and because the

Vietnamese students, unlike today’s dec-

adent American youth, want it more.

Next, Comrade Stone and I went

to the Museum of the B52 and the Army

Museum, and the question rang louder

because running an effective Fansong

and Tall King radar required sophisti-

cated training—from simple farming to

air defense in less than a generation

proves what dedicated education can

do if the students are anxious for the

knowledge. Whether they fought for the

right or wrong ideology, their education

then and now defeats America’s hands

Page 16

The Last Flight West

down. The museums were well-planned and laid out, and the wreckage is wreck-

age; the story is how the wreckage came to be.

HISTORICAL VESTIGE

Huu Tiep Lake and the Wreckage of B52 Bomber,

Ngoc Ha Precinct , Ba Dinh District, Ha Noi. At

23.05 on December 27th 1972, the Battalion No72,

Air Defence Missile Regiment No285, shot down on

the spot a B52G of the US imperialist violating

Ha Noi air space. A part of the wreckage fell into

Huu Tiep Lake, Ngoc Ha Precinct, Ba Dinh District,

Hanoi. The outstanding feat of arm contributed to

achieving the victory “Dien Bien Phu In The Air”:

defeating the US imperialist’s strategic air raid

with B52 bomber against Ha Noi at the end of

December 1972 and creating an important change

that led the Vietnamese people’s anti-US resistance

for national salvation to the complete victory.

We are losing the educational race

at a rate that is beyond alarming, and that

presages more wreckage to come. This

small pond should be a required stop for

American military planners, including

those displaying five rows of ribbons and

other fancy badges—all in losing causes.

After absorbing the war’s detritus it was time to seek out lighter fare, and

we headed off to the veranda at the Metropole.

Before continuing, a background note is in order. I was in a fraternity,

yes I confess to it, and one of the events every Sunday morning was to rate the

engagements and the brides: who made the cut and who didn’t. The rating ses-

sions were raucous, bawdy, neither totally fair nor totally unfair, but nonethe-

less an indirect way to strike a blow against one’s social betters. It was in this

spirit that I approached the Metropole, one of the last great hotels in the world.

Our entrance was unconventional and perhaps not fully appreciated. We arrived,

me riding tandem, on a Honda christened “Red Rage”, that spoke Chinese, driven

by a Vietnamese affecting a piratical flair—a maître d’s nightmare. As we ap-

proached the hotel we noted at least twenty brides heading the same way, and

I couldn’t figure it out.

Comrade Stone waved off the hand orders of the chief of parking secur-

ity, who was immaculately dressed in a uniform that could have belonged to

a Mexican or South American general, (missing only the medals for killing

defenseless Indians.) We dismounted and left Red Rage in solitary splendor

The Last Flight West

Page 17

on a beautiful gravel walkway that led to the veranda. The maître d’, who I will

refer to as René, could not have been pleased to see us.

Up to that moment I had not paid too much attention to Comrade Stone’s

garb, but I soon realized that his bandana and overall pirate affect would make

any maître d’ shudder. As

any maître d’ shudder. As

for me, I wasn’t exactly

sporting Brooks. Never-

theless, we moved in with

calculated nonchalance.

Now René, although

Vietnamese, is French to his

toes, and he is cursed with

the knowledge that he must

attend obsequiously to guests

he knows to a certainty are

his inferiors on all fronts.

However, he must keep the

knowledge buried deep down in his psyche because to let even a whiff bubble to

the surface will result in his dismissal. This intellectual straightjacket results,

as it must, in a roiling cauldron of psychic magma that is beyond volatile. The

situation manifests itself in both entertaining and unpleasant ways and, as many

a refined woman will tell you, to be put down by a French maître d’ early in the

evening sounds a death knell to the prospect of sexual favors later that night.

The maître d’ understands this, and if you don’t you should, because contrary to

SI and NV’s beliefs, there are some things money cannot buy.

Comrade Stone, now somewhat less piratical in appearance having dives-

ted himself of his bandana, and I worked our way through several bridal shoots

on our way to the veranda. We are sure to be photoshopped out of at least a

dozen bridal pictures.

I told Stone straight out that I thought the veranda of the Continental now

scarcely deserved mention as an Affaire Nostalgique, and I had heard that true

insouciant hedonism existed only at the Metropole and nowhere else. We wanted

the table at the apex to control two fields of fire, as I had in the old days at the

Continental.

René seated us and thus began two hours that were beyond lots of fun. I

asked him about the conga line of brides who were descending on the Metropole

Page 18

The Last Flight West

and he explained that the Metropole was “the place” for a backdrop to their

wedding photos. Comrade Stone advised that it was a Vietnamese custom to

have the wedding pictures taken about a month before the event. Having been

burned three times in this arena I asked him, terribly ungallant, what happens

if the couple split up? Comrade Stone did the hissing sound favored by Arabs—

simply too outré for words—subject closed. René remarked, with just a slight

arch of the eyebrow, that some brides went to the Ethnological Museum, but

not many, and that silent arch clearly indicated they might as well have gone

to Siberia. The drinks arrived and what could they be but superb—it is the Metro-

pole, you know.

We studied the brides and then the rating game seriously began. We

watched young Vietnamese men maybe 5’ 2” tall struggle with their more zoftig

Vietnamese ladies, trying to lift them up, assuming poses that bordered on the

ludicrous. It was all there, and the game was on. Soon after we arrived an elder-

ly Australian couple took a nearby table, and for the next hour they were putting

them away at a good clip. The Australians began to exhibit near hysterical laugh-

ter at the Vietnamese couples, especially those engaged in the weight lifting con-

tests. They were becoming loudly drunk.

Comrade Stone, because I had my back to her, pointed out an elegant, old-

er Vietnamese lady, hard to tell her age, maybe forty-something, but you couldn’t

escape the price of the outfit, about $5,000, who was jabbering away on her cell

phone. I asked Stone what was the big deal, and he said she will start sobbing in a

moment, and as if on cue she did. Big deal. However, what followed was a bigger

deal in that a considerably younger Caucasian man, looking like a Brooks model,

ever so “embassy-like”, appeared in a Brooks 346 blazer and sat down by her

side. Speaking English no less, he poured oil on troubled waters, or appeared to

try to. Loud enough so I could hear the endearments, platitudes and clichés pour

forth from him like so much gentle rain. I could have written the script. If he

would just take her home all would be right in the world. Love bloomed as she

called for her car. I was pleased to see it was a black Mercedes. She got in the

driver’s seat—fatal mistake—but I was also pleased to see she had on a wedding

ring; clearly “home” was not on the menu. A public denouement and patch-up on

the veranda of the Metropole. This never would have happened at the Continen-

tal, although I have viewed what might be considered scenes on the Continental

veranda, she stabbing a fork into his hand for example, but the French generally

The Last Flight West

Page 19

keep their spats closer to the vest. As my first wife would say, “one just doesn’t

do that!”

The grading of brides was proceeding at a furious pace but I thought I

would have a little talk with René about the recent rapprochement. The Aus-

tralian couple were blotto by this time and I sensed if René could have hauled

them off in grain sacks he would have.

I queried René about the events, and ever the epitome of discretion he

opined, seulement entre nous, that such transactions were becoming more

common, and that this couple, he an “embassy type,” had been at it for some

time. Discretion prevented me from seeking a precise definition of “it”, but who

says you can’t have fun in John Kerry’s State Department. René confided that

the most spectacular melodrama had involved an Italian couple, starting with

wine in the face and moving on to vulgar screaming that could be heard in Sai-

gon. I asked if this was not bad for business and he said perhaps, but is there a

better venue for romantic meltdowns than the Metropole veranda?

The bride grading continued, and the couple that took it—she a bit older

with fine bones and wearing an off the right shoulder number, he considerably

taller, with soft Gucci loafers and no socks. He prominently displayed his no

socks approach to fashion by crossing his feet so everyone would see his Don

Johnson ankles. We told René it looked ridiculous and he agreed. The Austral-

ian couple were beyond recall and I told René he had better get them off the ver-

anda as they were bringing down the tone of the neighborhood. Who says local

color has to be ethnocentric?

“It’s so easy a child can do it!”

I then took my first motorbike lesson and failed to master a few funda-

mentals, such as how to downshift, how to brake and, better still, how to turn

right. Other than one slow crash when I tried to stop the bike going over by

braking with my hand, it was an unmitigated disaster. I did not break my wrist

but I did a more than adequate imitation. At this rate I would be a menace not

only to myself, but to everyone else. I told Comrade Stone, a most patient man,

that I would try it again tomorrow, but that we were now going to implement

Plan D. He asked what Plan D was and I told him it sure as hell didn’t involve

me driving a bike over 2,000 kilometers of mountain roads.

Page 20

The Last Flight West

Great day, great sport and I learned that a competent Vietnamese seven-

year-old has better coordination and bike skills than do I.

Day Four: Later

Cool, wet

Revolutionary fervor on full blast

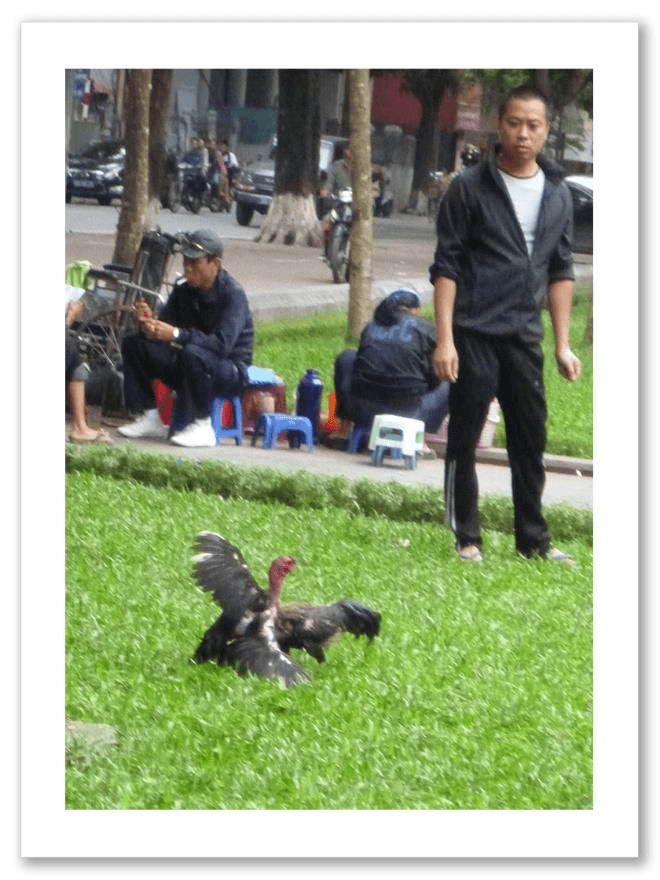

While riding around a park we came across a cockfight in progress being

watched closely by a small crowd. I asked Comrade Stone whether this was a

common occurrence and he said yes. The birds were heavy in oriental blood, and

I did not notice whether they had spurs,

I did not notice whether they had spurs,

but if they did they were lousy cutters.

I could not grasp the rules, but I did

notice that during a break both sides put

lots of water on their birds, an absolute

no-no to American cockers. Sotto voce

Stone observed that one of the spectators

looked worried; most probably he had a

sizeable bet. I checked out the spectators

but I could not detect any overt concern

on anyone’s face.

When I asked Stone about the

wisdom of putting lots of water on the

birds he answered that the water was

laced with a stimulant that lasted about

five minutes. During the war years,

Dan Deffenbach, an American cocker,

shipped a lot of roosters to South Vietnam, and the grey rooster in particular had

all the markings of an American gamecock. I am sure Dan is long gone, but here

in a communist country his legacy lives on. Strange that cockfighting is banned

yet the fighting is in a very public park.

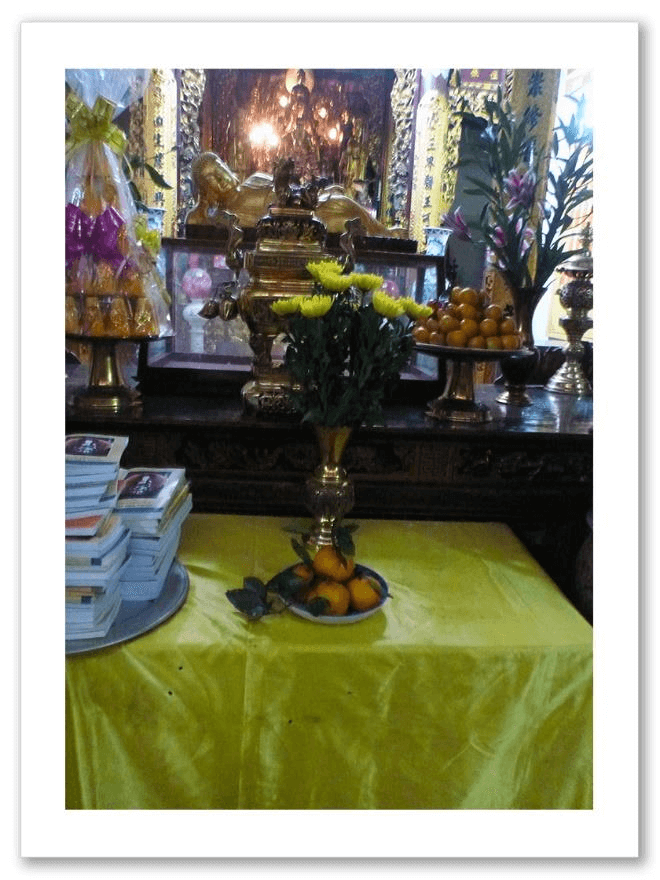

Yesterday evening I advised Comrade Stone that I wished to pray at a

Buddhist shrine with my family, and there must be no Jade Pagoda circus-like

atmosphere. He said he understood, and would find a quiet, contemplative place.

We hit the flower market, nothing like Bangkok, picked up yellow roses for two

dollars, and off we went. Stone delivered me to the Pholing Temple where we

were the only worshippers. Small, in the process of restoration, the temple

The Last Flight West

Page 21

presented an altar with a series of lesser Buddhas leading to what I must assume

was the top Buddha. None of the menacing size and quasi-terrifying aspect of the

Japanese temples, but this temple

Japanese temples, but this temple

was mine, and when the acolyte placed

my eleven yellow roses I got busy com-

municating with my family and Mab,

especially Mab, as I told her everything I

was planning. For an hour that seemed

like minutes, we four were together as if

nothing had changed. No one came to

disturb the reverie. However, as I left,

a cold blast of the West blew in when a

Bebe girl made her appearance. I knew

all about that spiritual ether or lack

thereof—I married one! I walked out

stronger than when I went in, and

looking forward to the challenge. Mab

lives and forgives me for “going north.”

There is no good Eng-

lish language newspaper

in Vietnam so I had to rely

on Comrade Stone’s phone.

With no BBC, New York

Times or Guardian, the re-

maining news reports were

heavily filtered by the

government. Stone and I

started a game called WWIII

in which he was tasked with

relaying all the news that

came through and decide

whether it counted or not. On this day I was tasked with explaining to him our

bicameral form of legislature and, even though I did not have much to go on, how

a particular vote swing might change U.S. foreign policy. First thing every morn-

ing Stone reported on the day’s world crises; I began to care less and less as I

Page 22

The Last Flight West

realized I could not influence any event of consequence. I had become, and was,

insignificant.

On my very first trip to Europe at the age of nineteen I was dropped into

Paris where I was so green I took a cab from Orly to the Hôtel de l’Opèra, failed to

grasp the distinction between old francs and new francs, was yelled at merci-

lessly for the size of my tip, and almost had to be rescued by the doorman. I was

a wreck. I was so shaken I took to hanging out at a sidewalk café that faced the

Opera House. I discovered glace vanilla, a lovely water-based French ice cream

which hits home even today—expensive, but worth every penny. I sat myself

down each day and the waiter would come up and say “la même chose” and I

would nod gravely and my courage came back. Subsequently I learned that my

café was the world famous Café de la Paix, and the French waiters were attend-

ant to my needs and even explained the country to me.

I thought, what better place to explain my government to Stone than an

old converted French Colonial office that served glace vanilla and a host of other

flavors. The place was called Fanny’s and over the next three hours and several

dishes of ice cream I slogged through the fields of bicameral government. I don’t

believe I did too well. In a one party system, which was all Stone had ever

known, the chairman of the Party had the one and only say, and that was that.

How could the Politburo or Central Committee go against the Party, especially

since most of them owed their allegiance to the Party chairman? How, indeed!

How could executive orders from the Oval Office go against the will of the Cong-

ress—how, indeed! I failed miserably with my civics lesson, but the ice cream

was great, though Comrade Stone considered it wildly extravagant. I did too,

but can anyone put a price on

but can anyone put a price on

traveling back fifty-eight years

to a Parisian street café where

the same glace vanilla held

sway. As the MasterCard ad

used to say, “Priceless.” Hanoi

was subtly seducing me.

It was late in the after-

noon, and Stone said only a

few tourists would be out and

we should visit the One Pillar

Pagoda. Spot on—nobody

The Last Flight West

Page 23

there, and it was an oasis of peace I could not have imagined. Hard to believe

that such a place merited being

burned down by the French. Even

harder to imagine that an atheist

Communist government would re-

build it. Contemplate that contra-

diction for a moment.

We next repaired to the

parking lot where I repeated the

previous day’s failure by slowly

crashing the bike into a sidewalk

railing and pinning my leg under-

neath it. It did not break the skin,

but would lead to an infection which

required I be treated, for the next

five weeks, in remote mountain

towns by the cutest pharmacists.

At this juncture I advised Comrade

Stone I was adopting Plan D, which was

Stone I was adopting Plan D, which was

that I would ride tandem and we would do

the trip as planned.

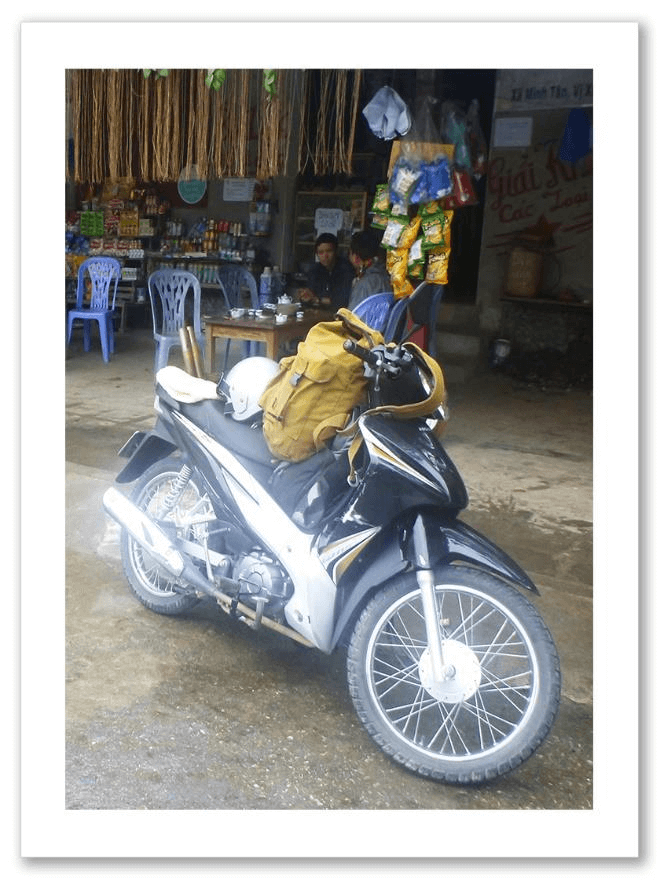

Thanks to Comrade Stone’s beyond

reasonable rates my daily travel expenses

equaled the cost of two movie tickets

without a box of popcorn. I was told to

pack no more than fifteen pounds and be

ready to leave early the next day. You try

packing for twenty-five days in the back

country with rainy weather in the offing

and a fifteen pound limit. Preparatory to

jumping off we visited the shop where we

were renting the bike, and I found quiet

comfort in the organization and operation

of the parts department. I was pleased

that the shop was ideologically pure, but

had some qualms about Mr. Goodwrench on meth.

Page 24

The Last Flight West

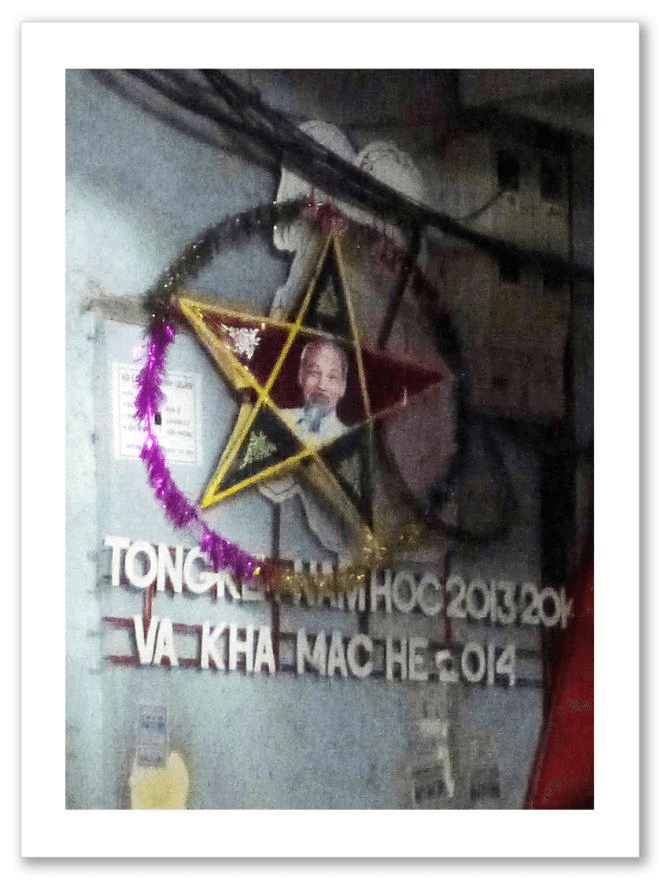

The evening before our departure

Stone introduced me to the electrical mys-

teries of the Quarter. When I expressed

skepticism as to how it worked and inquired

who was in charge, he smiled knowingly and

said it was a marvel of engineering—at least

for some lucky folks.

Funny how that late night encoun-

ter with the Scotsman had destroyed my

dream, but birthed a new one, and opened

up a whole new dimension of travel—tandem

motor biking in the far northern Tonkinese

Alps. Stone told me all I had to do was just

hold on, but privately at the conclusion of

the trip he confessed that when we set out

he didn’t think I would make it as far as Dien

Bien Phu, about two hundred and fifty miles away. Me, I was oblivious to his mis-

givings, but it wouldn’t have mattered anyway because I was on my way, and not

with fifty noisy tourists on a bus, to visit one of the major battlefields that deter-

mined, and continues to impact even today, the course of western civilization in

the East: Dien Bien Phu. Bring it on.

Day Five

Rainy, damp, cold

No revolution in the air

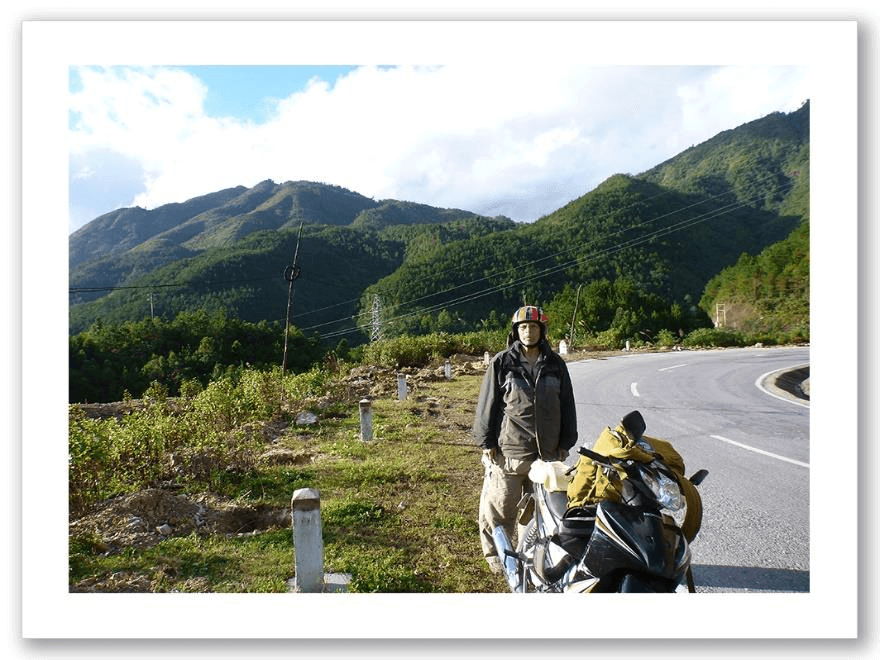

Early start, and as we load-

ed up the bags I attempted to affect

a nonchalant air, but failed miser-

ably. Deciding to keep my mouth

shut, I threw my leg over the back

pommel and almost didn’t make it

as the pain from the hard spill the

day before was killing me. Stone

and I wended, and “wended” is a

charitable word, our way out of

Hanoi.

The Last Flight West

Page 25

More accurately, we battled our way out, and I quickly learned that if

one is to survive the tandem motorcycle experience in Vietnam, the first muscle

that needs to be strengthened is the anal

that needs to be strengthened is the anal

sphincter. “Just hold on” was a gross

understatement. The real goal is to hold

on and not defecate in your pants. The

close calls just kept coming, and I had

yet to encounter the eighteen wheelers

driven by teenage kamikaze pilots with

but one agenda regardless of their des-

tination—get there first and take no

prisoners.

As we continued to head for Mai

Chau I learned a most valuable lesson:

There are No, repeat No, rules of the

road in Vietnam—survival is Darwin,

pure and simple.

It is worth noting that there are

areas of Vietnam with beautiful white

lines painted on the roads, and beauti-

fully uniformed traffic police wielding

lovely white batons to enforce the white

lines, but these officials are generally

busy shaking down the locals.

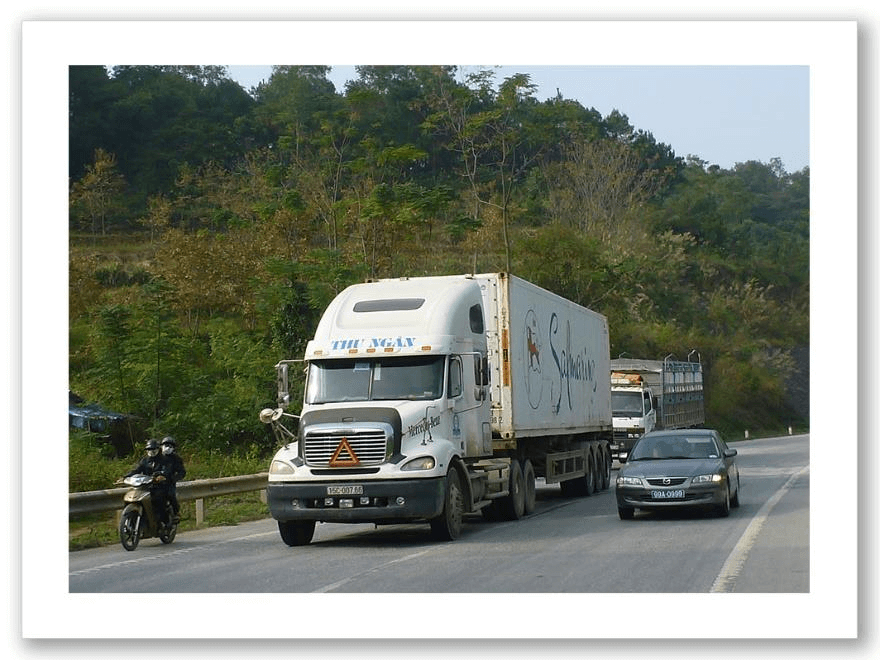

Vietnamese eighteen wheelers

have, I thought as a safety measure,

reflector triangles affixed to their cabs’

radiators. One theory is that the reflect-

ors allow you to see the trucks bearing

down on you so that you can take eva-

sive action. My own theory is that the

triangles are there to line you up so the

truckers can’t miss knocking you down.

Page 26

The Last Flight West

Traffic in town moves slowly and chaos reigns. Your odds of carefree

driving decrease as you move into the countryside and the roads narrow to

roughly one lane and three quarters. Trucks driven by the unhinged are coming

right at you and passing you, in your face and on your tail. I am not an adrena-

line junkie or an extreme risk taker (except on the Zambezi River) but for those

who crave a little excitement this is your thing. Your life is tied to your motor-

cycle driver’s skill, which is bad enough because you can do nothing about it,

The Last Flight West

Page 27

but, and this is the kicker, you have absolutely no control over the truck dri-

ver barreling towards you. As the roads narrow, the number of guys barreling

toward you increases dramatically, and

toward you increases dramatically, and

I can tell you that “just hanging on” does

not cut it. Just when you think you are

on a decent stretch of road, some cowboy

comes up and passes you on the right.

You simply must accept that you are

riding on a motorized bicycle with noth-

ing to protect you if you are hit, on roads

of dubious quality, with, as you get into

the mountains, drop-offs of thousands of

feet, confronted by other drivers whose

ideas of safety and yours do not remotely

coincide. No, you do not “just hold on,”

as your eyes are riveted on the road, and

if you are not concentrating it means you

do not understand the risks. I decided

that if, when we stopped, I could get off

the bike alive and not maimed, then it was a good day—and I was riding with the

best motorcycle driver in Vietnam. Those close encounters where I could reach

out three inches and touch the

out three inches and touch the

eighteen wheeler going the

other way, and feel the hot

exhaust on my face, did not

thrill me, but it did sometimes

cause me to question what I

was doing there.

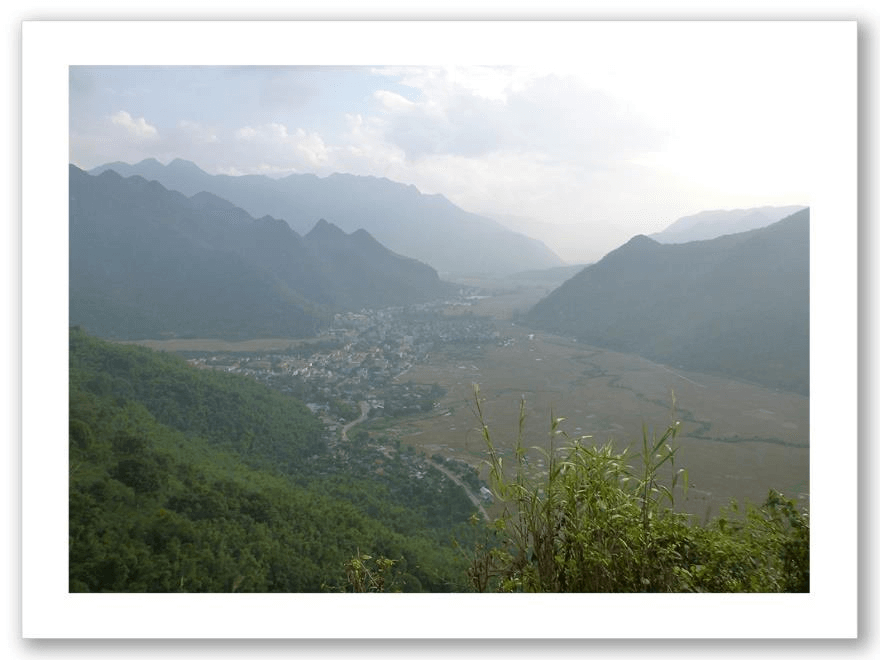

On the road to Mai Chau,

as we began our ascent to the

lands of the “Princess of the

Mists”; the haunting scenery

became increasingly enchant-

ed and surreal. As we contin-

ued up I feared for Red Rage’s well-being, and as we climbed higher I knew the

clutch was a goner.

Page 28

The Last Flight West

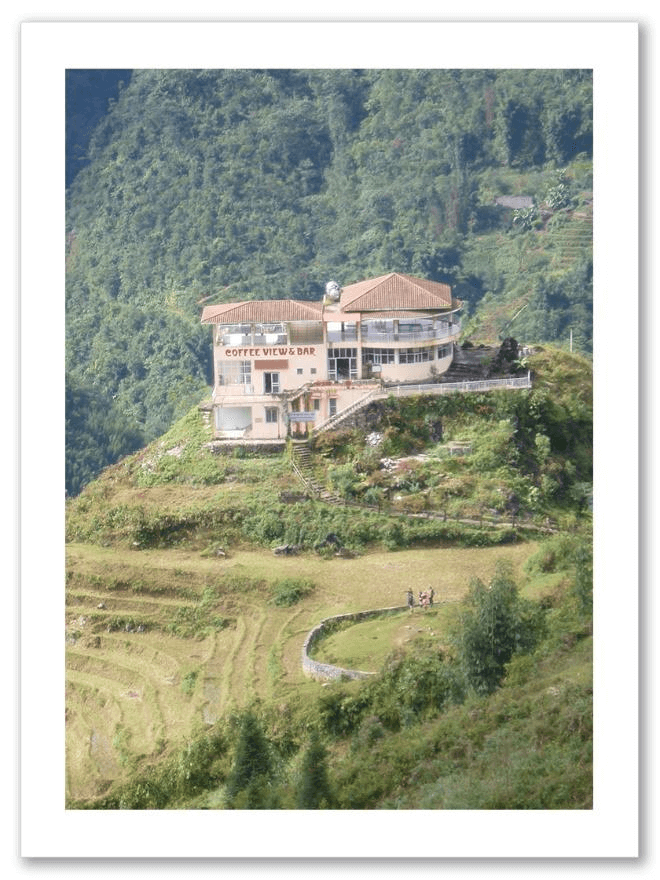

We were headed for Mai Chau where I had a free room at a little jewel of a

hotel. Our arrival at the hotel was the first and only time I had to pull rank. I

am not a communist, but in certain social settings I can exhibit communist

tendencies. The most polite receptionist indicated that, although my room was

paid for, Comrade Stone’s was not. I asked if there were two beds in the room,

and she said yes, but that it was not possible to accommodate Comrade Stone in

my room. Adopting my best Central Committee attitude I advised her I was a

communist, and I found it appalling, in a communist country, that a worker

should be treated in such a shabby manner—this would be duly reported upon

my return.

An immediate volte face, and yes, Comrade Stone could stay in my room.

First time I ever got anything for playing Red. Don’t know if I won a friend for

life, but Comrade Stone indicated the bed was very comfortable and beat a night

in the drivers’ dormitory by a mile.

While we were relaxing at the restaurant a spanking new van parked and

discharged eight female Chinese Buddhist monks, in brand spanking new cross

trainers no less, and also, by the look of their garb, two Southern California

“seekers”; altogether it was a sight to behold. The California contingent was in

dayglow, in marked contrast to their Nicherin sect sisters in their stark yet

elegant robes. East and West, yin and yang before our very eyes.

As dusk was approaching we were told that we must hurry if we wanted

to visit a typical Montagnard village about four kilometers distant. We dutifully

boarded Red Rage and moseyed over. The village was called Ban Lac and it

turned out to be a tourist trap on a grand scale. Once in Ban Lac it is very hard

to find your way out. As night began to fall we went from one end of the village to

the other and I thought, if this is what we could look forward to up north I had

made a bad mistake. Businesses were closing down; we were the only customers,

and we made polite conversation and left. We got out alive which to my mind was

no mean feat. Miss it at all costs.

As we headed back to the hotel, emerging from the paddy field like some

brown caterpillar with two dayglow tail pieces were the female monks. No chant-

ing, just moving along. I decided that if the path to enlightenment required ram-

bling around in paddy fields fertilized by human feces and inhabited by two of the

world’s most poisonous snakes, the cobra and the krait, this spiritual mountain

was too steep for me to climb. However, some folks believe the “A” train can get

you to heaven, and I wondered just what, if anything, was going on in the minds

The Last Flight West

Page 29

of those two Southern California dayglow types as they wandered around paddy

fields in the dark.

Our excursion was not a bust as it taught me a valuable lesson—Do Not

Drive At Night Under Any Circumstances. We hit the road in darkness and I

immediately realized night driving is a far more dangerous proposition than

day driving which is hair-raising enough. Halfway to the hotel we were forced

off the road by a truck that passed so close I could read, in the pitch dark, the

tare weights on the container, and the exhaust was so hot it almost burned. This

excitement was immediately followed by a near head-on with a cyclist. That was

enough for me, and when we arrived at the hotel I told Comrade Stone no more

night driving. We violated that rule only once, with the same near disastrous

consequences.

Beautiful room, beautiful bed. I fell asleep with visions of tourist trap

villages dancing in my head. One step closer to Dien Bien Phu.

Day Six

Cold, wet, rainy

Although it was winter, a lovely

flower greeted us at breakfast where we

tarried a bit long before setting off. Today

we began the second leg of our journey to

Dien Bien Phu. The road narrows and we

start to climb, putting great strain on Red

Rage’s clutch, but we have settled into

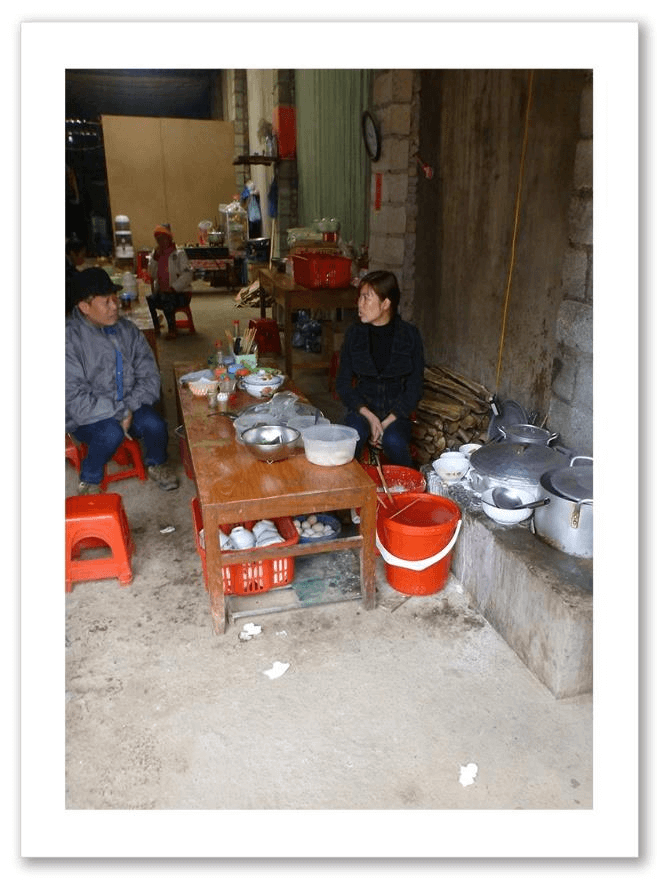

something of a rhythm. We try to eat

breakfast daily, but sometimes don’t, and

by mid-morning we are at some pho shop,

after which we stop for lunch and then

dinner. Much on the menu is not to my

taste.

On our way to Son La we viewed

an old Russian hydroelectric project and

as I looked downstream and saw the tell-

tale brown color I tried to imagine the silt

build-up that had to be taking place—the bane of many American dams. Comrade

Stone pointed out that the Vietnamese use the silt for agricultural purposes and

Page 30

The Last Flight West

the dam, although somewhat dated, is still cranking out vitally needed power

for the expanding light industry in the area.

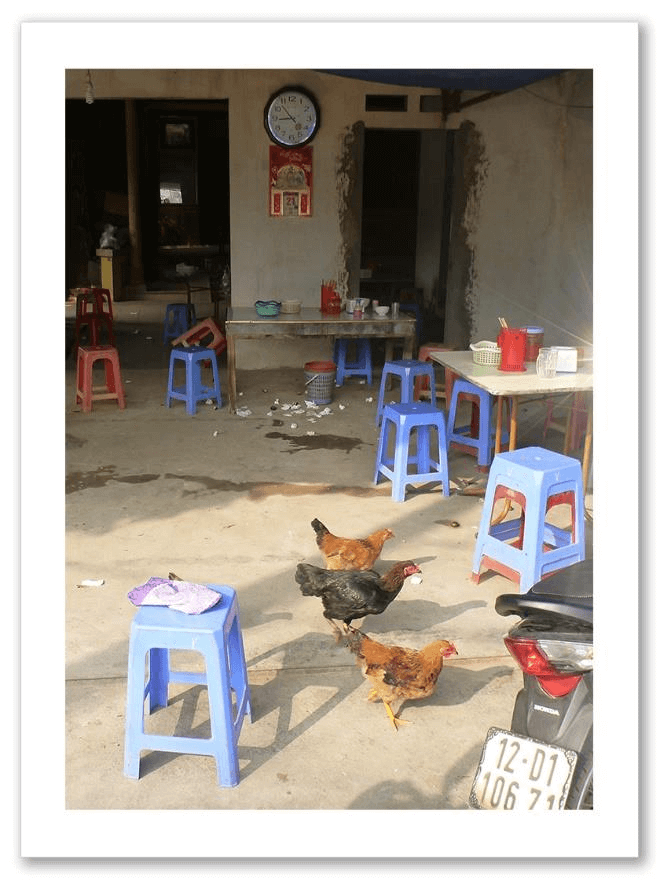

While eating at a pho place yesterday in the town of Hoa Binh I asked,

innocently enough, just what the town was based upon. In perhaps one of the

greatest putdowns I have ever heard, Stone answered “There is really no need

for its existence.” You can’t

for its existence.” You can’t

do better than that.

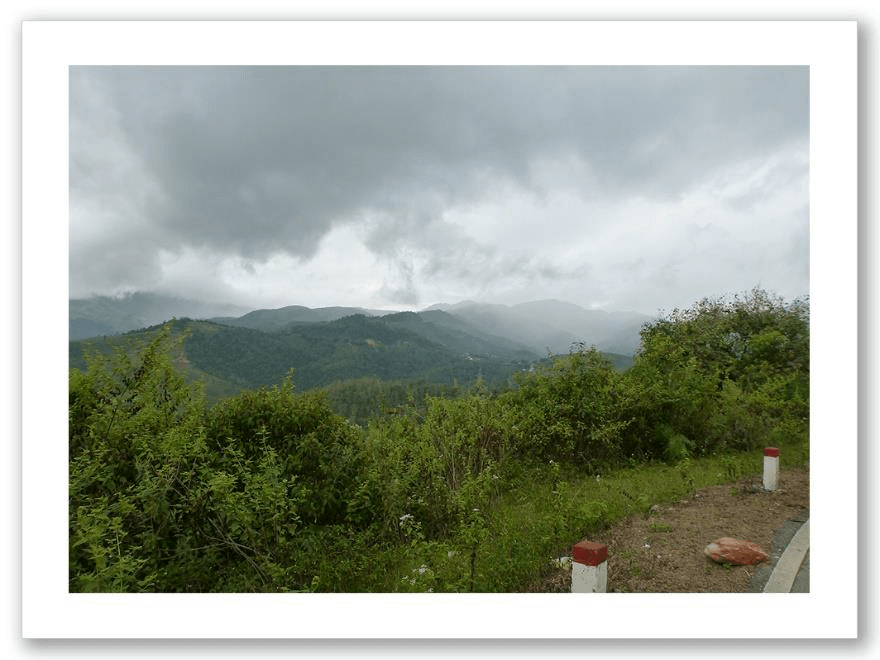

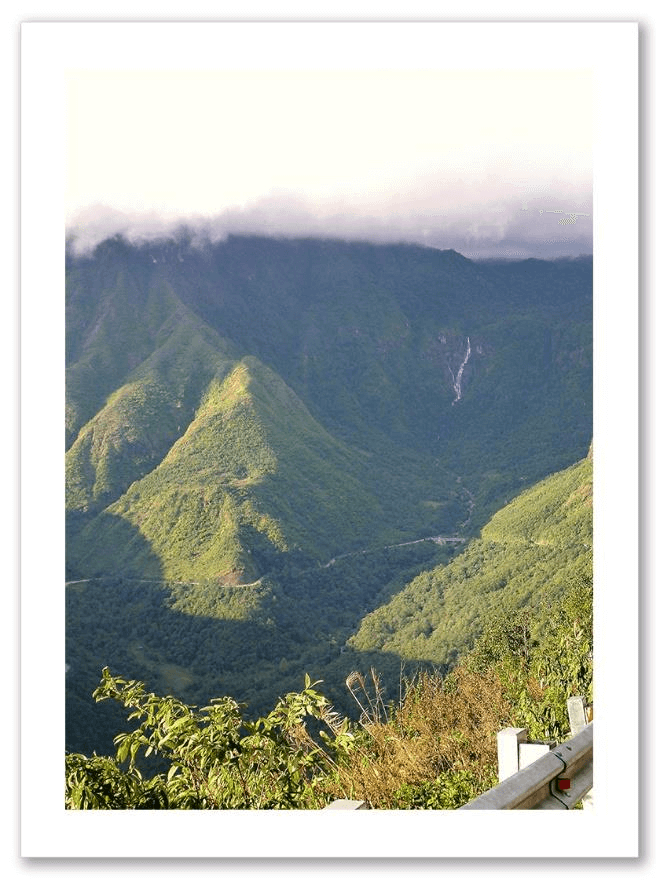

We started climbing in

earnest, in rainy, cold, misty

conditions, and the haunting

mountain views came at us

one after another (as did my

views of the drop-off if we

missed by six inches.) The

seduction by mountains

and mist had begun, and

continued every day of the

trip. Red Rage was constant-

ly under siege, and we rested at a pho shop located on what appeared to be a

farm. A billboard displaying a large Holstein cow brought a smile to my face.

This billboard changed my Vietnamese eating habits in a most healthy way.

For approximately five years my father and I ran Owl Brook Farm, the

most spectacularly unsuccessful dairy farm in the history of the world, and we

did this for two reasons. First, my father loved Holstein cattle, which will give

twenty-six quarts of milk, but with a low butterfat content. The second reason

was he thought we could compete with Wisconsin farmers who had thousand acre

farms to our two hundred hardscrabble hillside acres. Sadly, as we were to learn,

size matters. In those days high butterfat was good, now it is damnation, so in

order to increase our butterfat content we had to add Guernsey cows which, if

lucky, give about ten to twelve quarts, but high on butterfat. I have a longstand-

ing hatred of Guernsey cows because they ate as much, shit as much, but gave

one third less milk than Holsteins. I have bitter memories of our having to flush

a day’s work down the drain because a milk inspector would not give us a pass on

the butterfat content.

Here I was “in the middle of nowhere” staring a Holstein cow in the face;

on a billboard, but still a Holstein cow. I decided to investigate.

The Last Flight West

Page 31

I spied several plastic cups of what I thought looked like homemade yogurt,

so I got Stone involved and he asked about the billboard and the cups. The pho

shop proprietor said I could go to her barn and check out her herd—what herd?

I had not seen any cows. She gestures that I should walk down the hill a bit. And

so I walk to her barn, which was spotless, and right there was a DeLaval milk-

ing machine, same as ours, and forty-two head of Holstein with not a damned

Guernsey in sight. Stone and I walked back up to the pho shop where the pro-

prietor explained that we were in Vietnam’s largest dairy producing province.

The government had recently launched a new and expanded processing plant

and was planning to enter the export market.

When I told her our story about butterfat content she had trouble grasp-

ing the concept as her country’s milk producers were not looking for more than

3%. I knew my father was looking down on this, smiling and saying I told you

so. My retort was, you were about seventy years too early. I tried some of her

homemade yogurts, four to be exact, and she showed me the brand name to

whom she sells her milk. I dive in—it’s terrific stuff. From that moment on at

every food stop I look for Vietnamese yogurt. Pho shop owners are not pleased;

me, I am in food heaven.

We started climbing again, and hit Son La which is nothing but a city. We

found a $15 hotel and went to bed cold and tired. One leg closer to Dien Bien Phu.

Day Seven

Cool, misty, damp

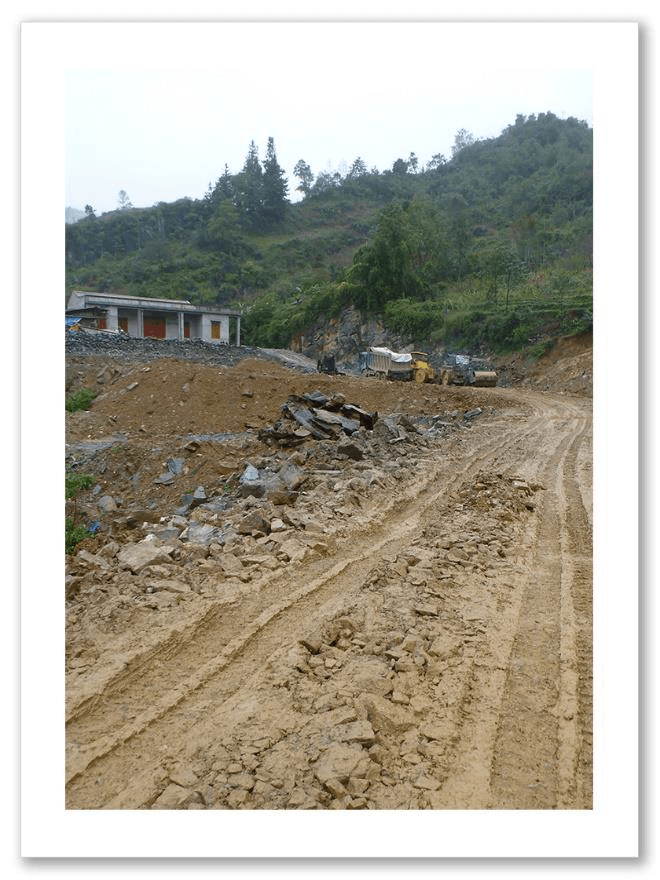

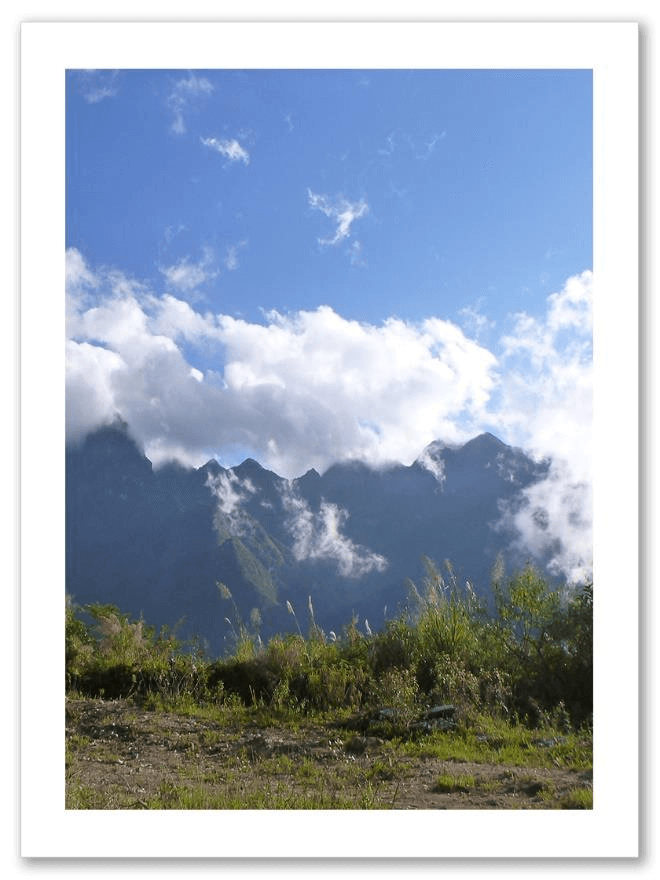

As we moved higher in-

to the mountains, rocks began

to appear in the road with in-

creasing regularity. Vietnam

suffers from landslides and

there have been many attempts

to control this problem. During

the war the Navy had a very

effective low level penetration

night bomber called the A6

which initially flew undetected

quite successfully under radar

coverage. The Vietnamese

Page 32

The Last Flight West

response was primitive in that it involved old single shot rifles. The shooters

would lie on their backs and when they heard a plane, shoot in the air. This sim-

ple exercise gave birth in naval aviators’ jargon to the term “Golden Beebees”.

It was only by the wildest of chance that you could be hit, but there were times

when this happened. The analogy to the rocks in the road is most apt because

although it rarely happens, when it does the results are devastating.

The day was cold and rainy when we started out and our glasses were soon

spotted with water. We could barely make out our surroundings as we spent the

next thirty kilometers struggling up the Pha Din Pass. I am told the scenery is

magnificent—we just couldn’t see it. However, this caused me to pay more atten-

tion to the outer edge of the road, and in my estimation we had about eighteen

inches between us and a two thousand or more foot drop into hell, a never to be

found again hell at that. It also seemed to me that both the cars and the bikes

passing the slower eighteen wheelers were more aggressive, and the number of

close shaves rose dramatically.

It was about half way up the pass that I saw the result of a nature-made

golden beebee. The big rock had crashed through the cab door of an eighteen

wheeler straight through to the other side killing both driver and helper. Bad

luck, assuredly, but I must confess that after driving past that accident when-

ever I saw those boulders near the road I always peeked a look upside—one nev-

er knows when another one’s coming.

I had always wanted to walk the battlefield of Dien Bien Phu, as it had

a personal connection to

a personal connection to

my family and, in my mind,

marked the first step in the

eventual defeat of the Amer-

ican Army—the first battle

when the East turned Red.

Two books, years apart, lay

it all out: Bernard Fall’s Hell

in a Small Place, and Fredrik

Logevall’s Embers of War. I

had immersed myself in both

and was pumped to see it all!

The Last Flight West

Page 33

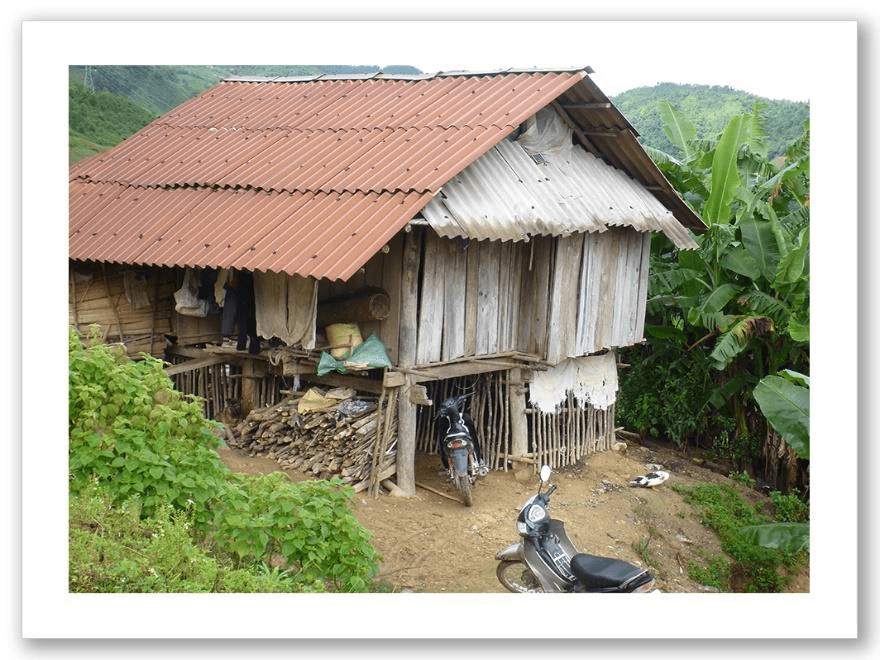

As we continued up we encountered the “Princess of the Mists”, traditional

up-country homes, roast dog for lunch, and tasteful monuments to Vietnamese

valor. We struggled on and I

valor. We struggled on and I

thought this must be taking

a terrible toll on the clutch,

brakes and second gear. No

mind, we were soon going to

see, in all its glory, the battle-

field where a modern West-

ern army was defeated by

a Southeast Asian peasant

army, generaled by a “native”

commander.

We arrived early in Dien

Bien Phu and secured our

$15 hotel. A couple of hundred yards away we were smack inside a good sized

city. I thought I would explore a bit, and directly opposite the hotel was the Dien

Bien Phu shopping center. On its front, which was about the size of a city block,

in plastic, no less, was a world famous picture of Viet Minh waving the triumphal

flag over the bunker of General Castries. The image is color coded, the victors in

red, losers in blue, against a white background.

As I approached this cavernous emporium I could hear, at an earsplitting

level, unintelligible boom box music. I entered gingerly, trying not to be at odds

with the hip-hop gibberish and local sensibilities. Everyone inside was dressed in

Southern California mall clothing. The cashiers, if not bopping to the music, were

restraining the impulse to do so. As I examined this curious place I saw they had

everything except furniture, and all the goods were made in China. Hard to des-

cribe except that this was mass merchandising, with a logo out front that, to my

way of thinking, debased the military victory. Hey, I thought, it’s their country

and they can do with it as they wish, but it brought to mind the magnificent job

the United States Park Service does at Gettysburg. Sure land is expensive, but

this place is of national, beyond national, significance. This is where the revolu-

tion triumphed, and now this enormous store is snuggled right up to the battle-

field. Hard to comprehend. Attack the battlefield tomorrow.

Page 34

The Last Flight West

Day Eight

Warm, humid

Bernard Fall in his book Hell in a Small Place brilliantly sets out the stakes

for France and the Western world, and the fallout from the French defeat is still

being felt today. Indeed, General Westmoreland adopted the same strategy as

French General Navarre, and although Westmoreland was not militarily defeated

at Khe Sanh, and inflicted grievous casualties on Giap’s army, the fact remains

that several months later, after the Americans withdrew, a photo flashed round

the world showing Viet Cong troops waving their flag on the Khe Sanh runway.

What a propaganda coup.

The French fought a set piece battle with the hopes that a Viet Minh defeat

would strengthen France’s negotiating position at upcoming talks to be held in

Geneva. The place was selected, “bad ground” as Union Cavalry General John

Buford would say, with several fortified strong points in the valley.

With traditional Gallic flair the designer of the fortifications named the

points after his mistresses—eight, I believe; the guy really got around. There is

no information about how his wife, mistresses, or, for that matter, the husbands

of his mistresses took being introduced onto the world stage in this manner.

Suffice it to say, because both sides were aware of the political stakes, the

Vietnamese, at terrible cost in terms of loss of life, attacked many of the strong

points. Both sides realized that if strong point Eliane (A1 Hill, in Vietnamese

military thinking) were not taken or defended successfully, the campaign would

not be a win for either side. The fighting over several days was beyond ferocious.

Eliane eventually fell, and it is the cornerstone of the battlefield, or I thought it

would be.

Initially, a good friend was concerned that our visit would not be satisfying.

She had information that no competent guides were available and that we would

therefore not get the full flavor of the field. She need not have worried; guides

would have been almost superfluous. Look, this is big stuff, and the Eliane site

we viewed simply falls way short of conveying the courage demonstrated by both

sides. I found myself gazing at a very small hill, and even in my debilitated con-

dition I did the climb, making it in three stages. The site is surrounded by some

scraggly barbed wire, and when you get to the top, except for the cemetery, the

battlefield is non-existent. Small capitalist shops have overrun this monument

The Last Flight West

Page 35

to the revolution. One only

wishes the United States Park

Service could be turned loose

with a bulldozer. Forty thou-

sand souls, give or take ten

thousand, perished here.

Their memory is not well

served by this tatty tableaux.

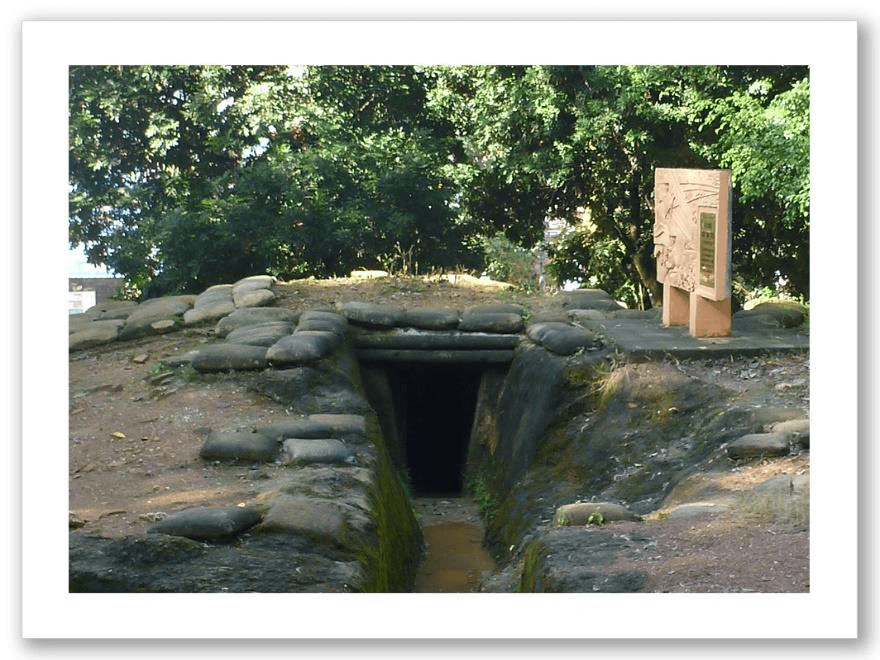

In order to ascend to

Eliane you must first pierce

the surrounding tourist shops,

no small feat, and you must

make this push both coming

and going. Thoroughly disillusioned, Stone and I plowed into town where we

discovered seven, no less, very stylishly dressed Vietnamese young men, all on

their cell phones, on the verandah of the Windows Café—this at least was worth

a look.

Window’s Café was definitely a find; the closest thing to a French café this

side of France. I ordered a Pernod, and although I have not had a drink in sixty

years, I lifted one to the paras

years, I lifted one to the paras

who jumped in on the last day,

knowing to a certainty that

they would be captured or

killed. Almost all perished.

I saw that Comrade

Stone’s focus was not on past

Vietnamese glories, but on the

pressure car wash across the

street that was doing a land

office business, and how he

could raise the capital to get

one started. We stayed at

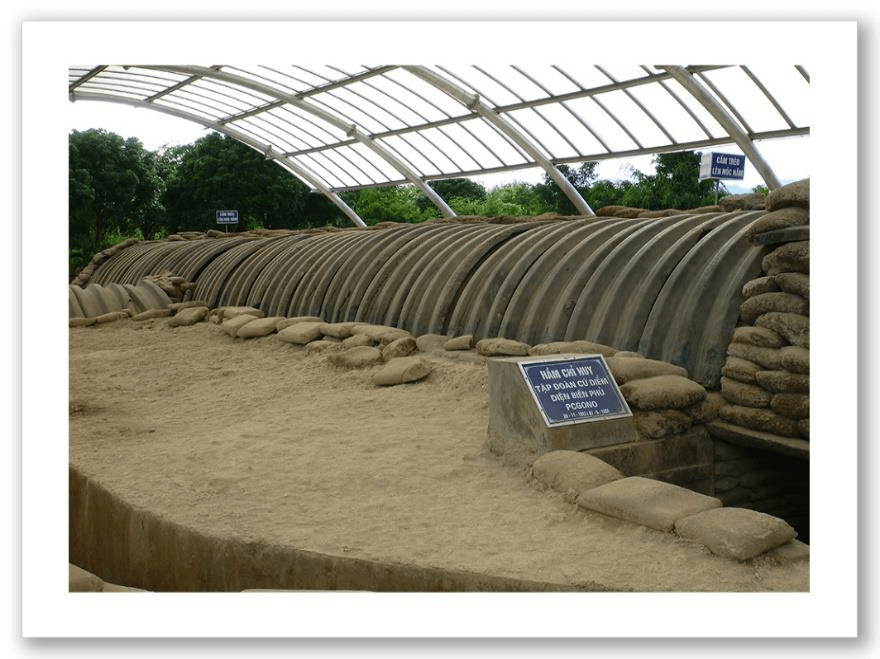

the café for several hours and then visited Castrie’s command bunker which has

been beautifully preserved, right in the middle of a series of small businesses, in-

cluding several mobile phone dealers. Although not yet surrounded by souvenir

Page 36

The Last Flight West

shops (and likely soon to be as overrun as Eliane) here too was a clever tourist

trap—you could not get in to see the bunker unless you passed through the shops.

Later that evening, as I

spent a few hours dealing with

my disillusionment, I contem-

plated again the number of

sporty and stylish young men

on the verandah of the Windows

Café. Then I realized that I was

in the land of the “brown fairy”

which was much more profit-

able than any car wash! Let

me see light—hard to square

with the Viet Minh’s valiant

sacrifices.

Day Nine

Hot, humid

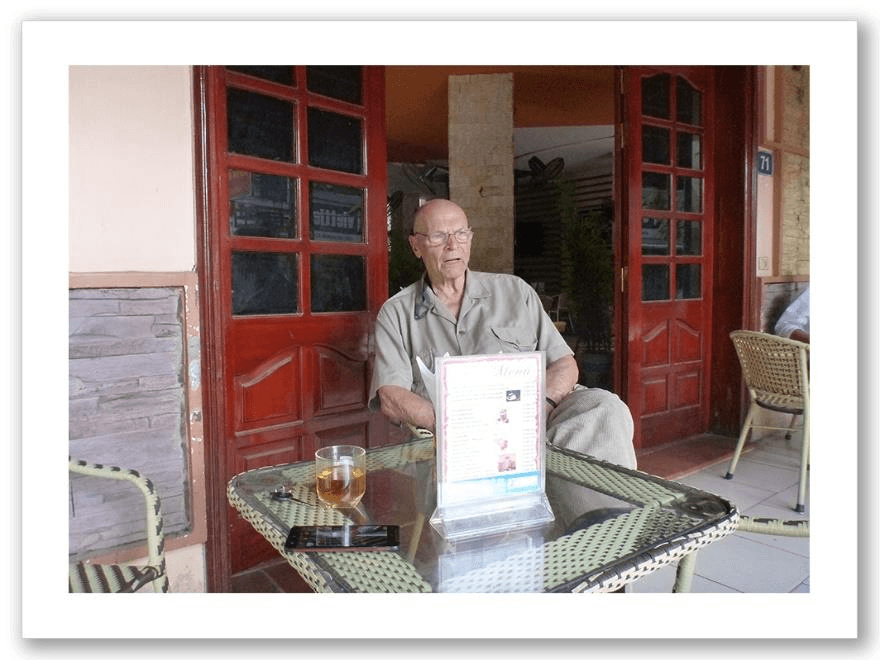

Started the day as any civilized person would do, at the Windows Café

watching the beautiful but undeserving rich banging away on their cell phones.

Then on to the recently completed Victory Museum.

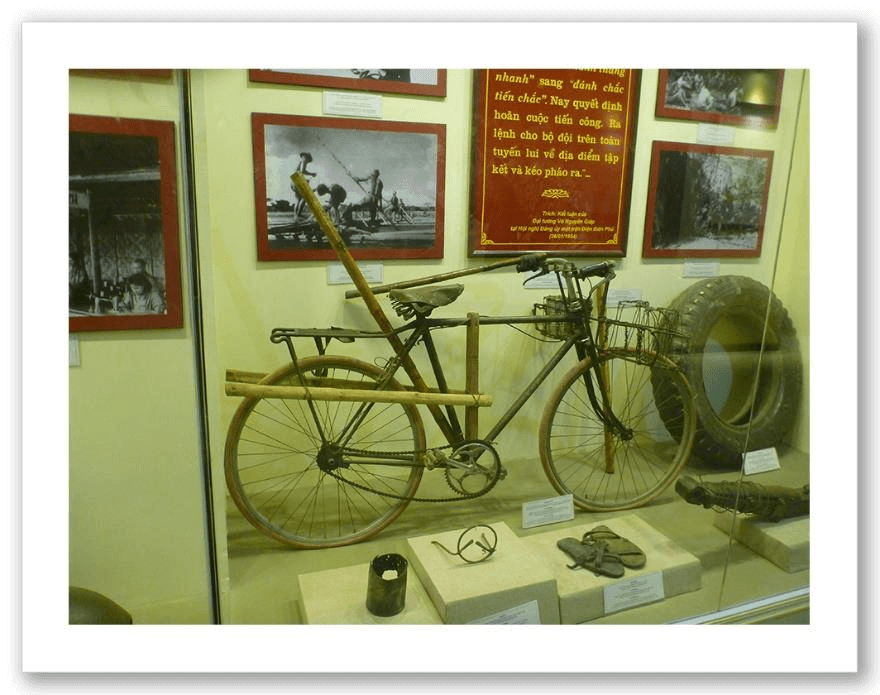

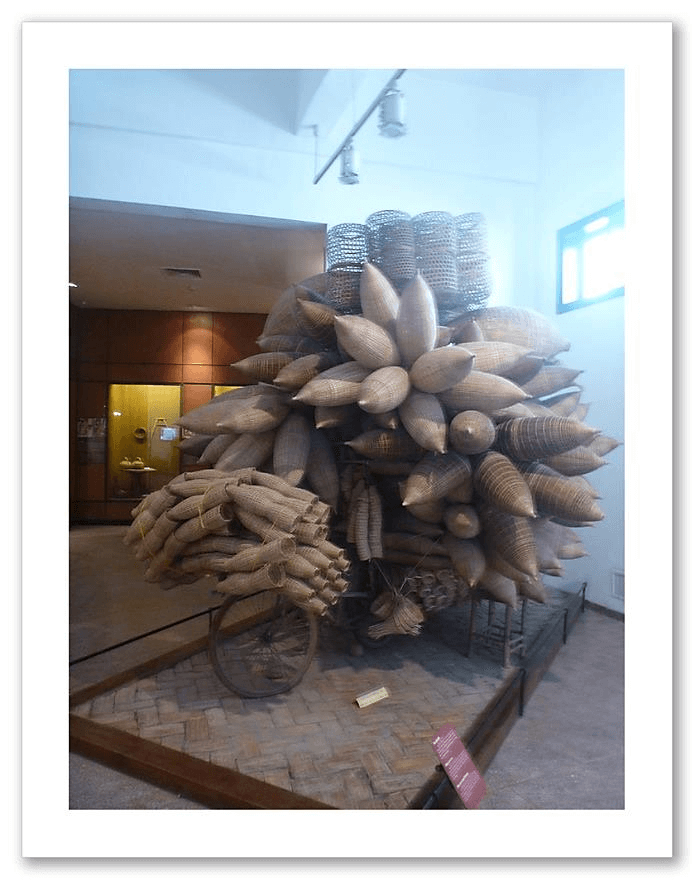

The battle and how it was won was starkly illustrated by Vietnamese

logistics and French logistics. Despite the disastrous site selection for a set

piece battle, French logicians

piece battle, French logicians

indicated they could support